NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Global Health; Committee on the Evaluation of Strengthening Human Resources for Health Capacity in the Republic of Rwanda Under the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Evaluation of PEPFAR's Contribution (2012-2017) to Rwanda's Human Resources for Health Program. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2020 Feb 13.

Evaluation of PEPFAR's Contribution (2012-2017) to Rwanda's Human Resources for Health Program.

Show details

HEALTH IN THE RWANDAN LABOR MARKET

In 2018, Rwanda's population was recorded at more than 12 million, with a working age population of 6.9 million and a labor force of approximately 3.9 million (NISR, 2018). It also has one of the highest rates of female labor force participation and is the only low-income country of the five countries (Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Rwanda) that has closed at least 80 percent of the gender gap (Thomson, 2017; World Bank, 2018). The latest Labor Force Survey from the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) reported that of the population of 3,207,336 employed individuals, 49,072 (1.5 percent) are working in the field of human health and social work activities (NISR, 2018). The health workforce has increased in both number and proportion at a rate of 6.9 percent since 2002; data from the Rwanda Population and Housing Census reported that the health workforce numbered 15,084 (0.46 percent) in 2002, and 29,413 (0.7 percent) in 2012 (NISR, 2014).

Health Workforce by Cadre

The 1994 genocide against the Tutsi nearly destroyed the health infrastructure and resulted in acute shortages of a supply of qualified and specialized health workforce, which hindered health service delivery and served as a major barrier to HIV care and treatment. In 2009, it was estimated that a 14.2 percent rate of health workforce growth per annum was required, according to Rwanda's population growth rate at that time (Kinfu et al., 2009).

Between 2009 and 2015, as Figure 6-1 illustrates, the number of health workers in Rwanda remained relatively consistent, with 7.8 to 8.9 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 people (MOH, 2015). When disaggregated by cadre, the majority of these health professionals were nurses (7.27 to 8.31), with significantly fewer doctors (0.58 to 0.64) and midwives (0.05 to 0.8). More recently, Rwanda was reported to have 1 physician (2018), 7 nurses and midwives (2018), and 3 other health workers per 10,000 population density (Open Data for Africa, 2018).

FIGURE 6-1

Doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population. SOURCE: MOH, 2015.

However, this was still far below the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended critical minimum threshold of 23 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 people in 2006, and even farther below the newer (2016) threshold of 44.5 per 10,000 (WHO, 2016). This shortfall represents a production challenge, meaning there is an insufficient number of trained health professionals relative to the need.

In 2011, 625 medical doctors, 8,273 nurses, and 240 midwives were providing care in Rwanda's referral and district hospitals and health centers (MOH, 2012a). In 2015, it was reported that there were 114 pharmacists, 1,545 laboratory technicians, and 263 anesthesia practitioners in Rwanda (MOH, 2015). Most doctors in Rwanda are general practitioners and perform a majority of the surgical care; 82 percent of the general surgery and obstetric procedures are performed at district hospitals (Kansayisa et al., 2018). Only about 50 fully trained surgeons and 170 anesthesia technicians were reported in Rwanda in 2012 (Petroze et al., 2012).

Compounding the shortage of doctors are absenteeism and the presence of “ghost workers,” people who draw a salary from the public sector although they are mostly absent. Doctors in urban areas combine public- and private-sector work, and usually at the cost of public-sector health service delivery through their lack of attendance (Lievens et al., 2010). Patients and health facility staff alike benefit from the doctors' time and expertise, but absenteeism leads to low quality and inadequate health care due to low output and productivity (Lievens and Serneels, 2006; Scheffler et al., 2016). The Rwandan government initiated a pay-for-performance strategy to improve the quantity and quality of health services provided in the public sector, making positive contributions to health worker performance (Ngo et al., 2016; Sekabaraga et al., 2011; Suthar et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2014).

Rwanda is relatively better resourced with nurses, who predominantly staff health centers, where 85 percent to 89 percent of the mostly rural population receives care (Iyer et al., 2017; Uwizeye et al., 2018). As one approach to help alleviate the shortage of HRH and linked to decentralization of the health system, the health sector introduced task shifting1 in 2009, shifting many clinical decisions and activities to nurses and community health workers (CHWs), including in the delivery of HIV care. With a deficit of physicians, task shifting would increase the ability to care for patients and would also decrease labor costs of the HIV program. The Ministry of Health (MOH) transferred the ability to prescribe antiretroviral therapy and provide routine follow-up care of HIV-positive patients on first-line drugs without complications to nurses (MOH, 2009b). The program trained more than 500 nurses to deliver HIV care and has achieved high levels of retention and improved patient health outcomes (Nsanzimana et al., 2015). The 2013 HIV and AIDS National Strategic Plan reemphasized task shifting of routine HIV care to nurses and the upgrading of nursing skills to equip them to care for pediatric patients and those on second-line prescriptions (MOH, 2013c).

Through further task shifting and a reformation of the national community health system, care for 80 percent of the disease burden was offloaded to CHWs at the village level through health promotion activities as well as preventive, diagnostic, and curative care (Binagwaho et al., 2012; Condo et al., 2014; MOH, 2013b). The Rwanda CHW Program was established in 1995, growing from 12,000 CHWs to now approximately 45,000 (RGB, 2017). Each village has three CHWs—a pair of general CHWs (binomes), who provide community health, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS prevention services, and a maternal health worker (animatrice de santé maternelle), who provides infant and pre- and postnatal maternity care. CHWs are elected by the communities they serve and undergo at least 6 years of education (Condo et al., 2014). Although task shifting has positively contributed to the supply of adequately trained health professionals, there are still significant shortages of physicians and physician specialists in the health workforce.

Publicly available data from the MOH's Annual Statistics Booklet, Annual Report, and the Master Facility List demonstrate an increase in health workers across type during a period concurrent with the HRH Program (see Table 6-1). These numbers encompass the newly trained health workers who participated in the HRH Program, those who were already working in the health system, and those who entered the Rwandan health system after being trained elsewhere. The committee was unable to disaggregate these data by source or career stage.

Including physician specialists and general practitioners, there were 1,350 physicians in Rwanda in 2018, which translates to 1 doctor per 8,919 population—below the Fourth Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP IV) national target of 1 doctor per 7,000 population by 2024 (MOH, 2018a,b).2 Physician specialists, before embarking on specialization training, become general practitioners. Although trend data provide the number of health practitioners by level, these data do not highlight the number of general practitioners who became specialists, which might have some implications for achieving targets for generalists.

TABLE 6-1Number of Health Practitioners in Rwanda by Level

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | HRH Target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Practitioners | 604 | 625 | 683 | 684 | 709 | 742 | 783* | 1,182** | ||

| Physician Specialists | 150** | 197** | 567* | 551** | ||||||

| Nurses and Midwives | 8,202 | 8,513 | 9,230 | 9,607 | 9,590 | 9,661 | 10,758* | 11,384** | ||

| Community Health Workers*** | ~60,000 | ~60,000 | ~45,000 |

- *

Ministry of Health: Rwanda Master Facility List, 2018 (MOH, 2018b). The Master Facility list counts health workers in the following categories: General Practitioner, Specialist, A1 Nurse, A2 Nurse, Midwife, Lab Technician, Physiotherapist, Anesthetist, Pharmacist, and Dentist.

- **

Midterm review of the HRH Program (MOH, 2016). The definition of specialists according to the midterm review was “of specialized physicians in public-sector workforce with an M.Med., excluding those in exclusively administrative roles,” which may differ from “specialist physicians” as used in the Master Facility List, which did not include a definition.

- ***

Comprehensive Evaluation of the Community Health Program in Rwanda (LSTM, 2016).

As of 2018, 5 of Rwanda's 30 districts had more than 1 doctor per 7,000 population and 8 districts had fewer than 1 doctor per 25,000 population (MOH, 2018b). Likewise, Rwanda's 9,551 nurses equate to 1 nurse per 1,261 population, below the HSSP IV target of 1 nurse per 800 population, and the 1,207 midwives equate to 1 midwife per 2,504 women of childbearing age, close to the national target of 1 midwife per 2,500 women of childbearing age (MOH, 2018a,b). In total in 2018, there were 10.5 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population, an increase from 8.8 in 2011, before the start of the HRH Program and a 19 percent increase in total, led by a per population increase of 176 percent in physician specialists, a 10 percent increase in general practitioners, and 10 percent increase in nurses and midwives. However, Rwanda remains well below the Sustainable Development Goal index threshold of 4.45 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 population established by WHO as necessary to deliver essential health services (WHO, 2016). If Rwanda meets its HSSP IV targets, it will have 15 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population by 2024.

Data from the University of Rwanda indicate that although more medical students graduated from undergraduate and postgraduate training programs after the HRH Program started, there was variability by specialty (see Table 6-2). The higher numbers of graduates in 2016, 2017, and 2018 reflect the increase in enrollment rates in the first 3 years of the Program. A maximum likelihood time series analysis was performed to assess the statistical significance of this increase (see Chapter 2 section for the rationale and methodology). Results indicated that the total number of physician specialists graduating per year from 2014 through 2018 increased significantly (P < 0.001), compared to the 2007–2013 period (see Figure 6-2). Data provided by the MOH indicated most medical specialists were distributed with high numbers at Rwanda Military Hospital, CHUK (University Teaching Hospital, Kigali), and CHUB (University Teaching Hospital, Butare)—and with smaller disbursements, in comparison, in Ruhengeri and Muhima hospitals—most of whom were internists, pediatricians, obstetricians and gynecologists, and/or surgeons. The impact of reduced investments in the HRH Program on graduation rates requires more time to assess.

FIGURE 6-2

Total physician specialists graduated under the HRH Program by year. NOTES: The 2016 HRH Program midterm review indicates that in 2015 there were 197 specialists in Rwanda; the 2018 Rwanda Master Facility List indicates this increased to 567 in 2018. (more...)

Additional MOH data on nursing specialists indicated that 111 nursing specialists graduated from the first Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) cohort from 2015–2017, with the most graduates from the pediatrics specialty, followed by medical surgical, and critical care and trauma (see Figure 6-3). Although the MSN program is still in its infancy, the number of specialist nurses produced in its early years is promising and could contribute to continued specialization of nurses and the provision of specialty care, although more time would be needed to evaluate the sustained impact.

FIGURE 6-3

Total nursing specialists graduated under the HRH Program by specialty. NOTES: The MSN program's first cohort matriculated in 2015. Presented data show the first graduated cohort for the 2-year programs from 2015–2017. SOURCE: Graduation data (more...)

TABLE 6-2University of Rwanda Medical Student Graduation Numbers by Program

| Department | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery | 117 | 42 | 88 | 130 | 75 | 96 | 72 | 83 | 103 | |

| Postgraduate | ||||||||||

| Anesthesiology | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | — | — | |

| Internal Medicine | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 17 | |

| Pediatrics | 5 | 5 | 8 | — | 1 | 6 | 14 | 13 | 11 | |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 6 | — | 7 | — | 5 | 6 | 14 | 10 | 13 | |

| Ear, Nose, and Throat | — | — | — | — | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | — | |

| Family and Community Medicine | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | |

| Surgery | 4 | — | 4 | — | 4 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 4 | |

| Neurosurgery | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | |

| Orthopedics | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | |

| Urology | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | |

| Anatomical Pathology | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 4 | |

| Psychiatry | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 2 | |

| Emergency and Critical Care | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 6 | |

SOURCE: Graduation data provided by the University of Rwanda.

The Rwanda Medical and Dental Council, established in 2003, is responsible for registering and licensing all medical and dental professionals practicing in both the public and private sectors in Rwanda. Doctors are required to renew licenses annually after completing a minimum of 50 continuing professional development credits. The National Council of Nurses and Midwives registers and licenses nurses and midwives in the public and private sectors. Licenses must be renewed every 3 years. According to their data, the number of general practitioners, physician specialists, and dentists receiving licenses has been increasing (see Table 6-3). The number of nurses and midwives receiving their licenses peaked in 2014 when the licensing system was newer. Another peak would have been expected in 2017 or 2018 as licenses issued in 2014 came up for renewal, but this was not observed in the data. Across all cohorts, 58 students graduated from the Master of Hospital and Healthcare Administration (MHA) program; another 3 received postgraduate certificates, and 5 were expected to graduate in 2019.

Interview respondents across all stakeholder types agreed that more physician specialists were trained and more nurses with advanced skills were produced under the HRH Program. One MOH representative who received her medical training before the program began expressed appreciation for the improved skills HRH trainees gained under the program:

The HRH Program was amazing—helped cover the gaps in-country, including specializations such as pediatrics and internal medicine. There is a difference in the quality of training and doctors from before the HRH Program…. We had high level, skilled teachers from top tier U.S. institutions. When I was training, we didn't learn how to treat HIV or co-infections, so that is a big difference the HRH Program has made. We don't have to retrain the graduates coming out now; they are integrated into the system, and their education is providing them the required skills. They are very well equipped. (87, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

Respondents also credited the establishment of postgraduate specialty training programs in medicine and nursing under the HRH Program with producing more health workers with specialized skills. However, there were conflicting opinions on the distribution of these new specialists in medicine and nursing. One respondent from an international nongovernmental organization (NGO) commented that during a recent visit to a district hospital, he had observed that there were now 15 doctors, including physician specialists in obstetrics and gynecology and pediatrics, which was an increase from when his organization started working with the hospital (04, Other Donor Representative). Such increases were seen as strengthening the district hospital level and reducing the burden on referral hospitals (05, International NGO Representative). However, one international NGO respondent observed that despite the increase in the number of doctors, there was variation by specialty and uneven geographic distribution:

This last graduation round, I think for the first time I saw internal medicine graduates pumping up more rural district hospitals. Pediatricians have spread out a little bit more. I think the bigger residency programs have spread around a little bit further. I haven't seen any of the other specialties. So, most district hospitals don't have a pediatrician and … it's a part-time job and not a full-time placement. I don't think I have seen any advanced practice nurses spread out to the district level yet. (12, International NGO Representative)

TABLE 6-3Number of Practitioners Receiving Their License

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 61 | 70 | 83 | 102 | 106 | 120 | 117 | 103 | 93 | 95 |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 50 | 64 | 59 | 77 | 92 | 94 | 95 | 94 | 86 | 85 |

| Neurology | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Cardiology | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Dentistry | — | — | — | 21 | 28 | 50 | 48 | 48 | 38 | 47 |

| Pediatrics | 50 | 62 | 61 | 85 | 87 | 85 | 88 | 84 | 78 | 80 |

| Surgery | 27 | 38 | 44 | 60 | 60 | 65 | 59 | 57 | 57 | 47 |

| Anesthesiology | 23 | 27 | 28 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 28 | 29 | 26 | 26 |

| Psychiatry | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 12 |

| Emergency Medicine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 6 |

| General Practitioners | 413 | 448 | 487 | 606 | 612 | 726 | 822 | 864 | 893 | 850 |

| Nurses | 2,988 | 5,027 | 2,298 | 2,954 | 1,369 | 1,116 | ||||

| Midwives | 504 | 686 | 293 | 245 | 51 | 117 |

NOTES: 850 general practitioners received their licenses in 2018, while only 783 were in public practice, according to the Master Facility List. Physicians in private practice and those renewing their licenses but not practicing account for the difference. Per the Master Facility List, only 51 percent of all facilities in Rwanda are in the public sector, meaning a large portion of providers work in private, nongovernmental, and faith-based facilities.

SOURCE: Licensure data provided by the Rwanda Medical and Dental Council and National Council of Nurses and Midwives.

Data from the Master Facility List showed that in 2018, 447 of the 567 physician specialists worked in four districts—Gasabo, Huye, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge—while six districts had no specialists and another five districts had only one each.

Evidence from qualitative data collection supports the claim that the HRH Program produced more health care workers and academics with specialized skills who are feeding back into the health system. For example, of 25 HRH trainees interviewed for this evaluation, 9 went on to work in district hospitals, 9 went to work in teaching hospitals, 4 became University of Rwanda faculty, 1 continued studies in Rwanda, and only 1 left to pursue other studies in the United States (see Figure 6-4).

FIGURE 6-4

Career trajectory of interviewed HRH Program graduates following graduation. NOTE: HRH = human resources for health; MHA = Master of Health Administration; MSN = Master of Science in Nursing; UR = University of Rwanda.

There is also clear evidence of upgrading of nurses in the interview respondent sample. Before the HRH Program, 4 were working as faculty in district nursing schools, 5 were working as A1 nurses, and 4 were working as A2 nurses. All 13 nurses improved their skills by one level through their courses under the HRH Program and have returned to or continued working in the health system, with 4 working in district hospitals, 5 working in teaching hospitals, 3 serving as faculty at the University of Rwanda, and 1 working as an MSN tutorial assistant while she finishes her degree (see Figure 6-5).

FIGURE 6-5

Career trajectory of interviewed HRH Program trained nursing respondents. NOTE: HRH = human resources for health; MHA = Master of Health Administration; MSN = Master of Science in Nursing; UR = University of Rwanda.

Of 567 physician specialists in Rwanda in 2018, 222 (39 percent) worked at the national referral and teaching hospitals, 221 (39 percent) at private facilities, 46 (8 percent) at the intermediate level, and 78 (14 percent) at the peripheral level (MOH, 2018b). The distribution of general practitioners is different, with the majority (53 percent) stationed at the peripheral level and only 11 percent at the national referral and teaching hospitals (see Table 6-4).

RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION OF HEALTH WORKERS

Retention of adequately trained graduates is among the ubiquitous challenges facing the region and is key to addressing an imbalanced health workforce (WHO, 2013). While sub-Saharan African medical schools have expanded student enrollment, “faculty-related issues were most commonly identified as key to improving the quality of graduates” (Mullan et al., 2011). In a survey of 146 medical schools, 26 percent of domestic graduates were reported to have migrated from their respective home countries within 5 years after graduation, with “80 percent of that emigration being to countries outside of Africa” (Chen et al., 2012). Even so, the “assessment of retention strategies has been challenging because of the poor ability by most health systems to track medical school graduates” (Mullan et al., 2011).

TABLE 6-4Distribution of All Physician Specialists and General Practitioners by Health Facility Level

| Level | General Practitioners | Physician Specialists |

|---|---|---|

| National Referral and Teaching Hospitals | 85 (10.9%) | 222 (39.2%) |

| Intermediary Level | 64 (8.2%) | 46 (8.1%) |

| Peripheral Level | 417 (53.3%) | 78 (13.8%) |

| Private Facilities | 217 (27.7%) | 221 (38.9%) |

| Total | 783 | 567 |

SOURCE: MOH, 2018b.

The 2011 HRH Strategic Plan set a goal to increase the number of skilled, motivated, and equitably distributed health care workers in Rwanda (MOH, 2011a). However, challenges persist in meeting this goal, including high health worker turnover rates that result in insufficient staff to provide training for new health care providers (MOH, 2013a); low salaries; and a lack of career growth and opportunity for further training that leads to attrition and a move from public to private service (MOH, 2011a). Other difficulties encountered with the health workforce include poor social and economic incentives to work in health care, lack of management tools, and a weak human resources information system (MOH, 2009a). High turnover of trained service providers is a major hurdle in maintaining sufficient levels of qualified staff (MOH, 2012b). As seen in other countries, an exodus of health care workers from Rwanda after receiving training also needs to be addressed (Alleyne, 2015), though given the timing of this evaluation, it was not possible to assess whether the newly trained nurses, midwives, and medical specialists were retained in Rwanda. Several of these factors are discussed in more detail in the sections that follow.

Distribution of the Health Workforce

Rwanda's health worker shortage poses a major bottleneck for the population (of whom 10 million are rural) seeking health services. However, the challenges are more complex than volume alone. The health sector is suffering from geographic imbalances in the distribution of qualified health workers who favor urban areas, preference of workers for the private sector, and low levels of motivation and performance in the public sector (Lievens et al., 2010). Additionally, a lack of relevant data on health worker migration in Rwanda means neither the causes nor the effects of health worker migration are well established (Asongu, 2014; Scheffler et al., 2016). There is some information about the geographic distribution that suggests health workers' preferences to avoid rural areas. In 2006, only 17 percent of public sector health workers took a job in a rural area (Serneels and Lievens, 2008).

One study used valuation questions to assess the willingness of the incoming health workforce (students) to work in rural areas and found substantial heterogeneity. Individuals had lower rural wage preference for those who had a high intrinsic motivation to help the poor, had a rural background, or participated in an Adventist local bonding scheme (Serneels et al., 2010). Conversely, students had more reservations about wages if they were from a more prosperous background and could afford to be selective about their work location (Serneels et al., 2010). Additionally, Lievens et al. (2010) found that medical students were generally less inclined to work in rural posts than nursing students, but they were all inclined to work in these rural posts early in their careers. In an earlier study, location decisions were not only influenced by salaries but also by benefits (e.g., house and access to health care), job attributes (e.g., access to training, promotion opportunities), access to infrastructure (e.g., electricity, water, quality housing, roads, and transport), and location-specific factors such as access to schools for children (Serneels and Lievens, 2008). One doctor working in a rural district in Rwanda noted a lack of career development in rural areas (Serneels and Lievens, 2008).

There is also migration in the Rwandan health workforce between the public and private sectors. The public sector is the biggest employer in the health sector in Rwanda, but it is not necessarily preferred by the health workforce. Lievens et al. (2010) found that 40 percent of nursing students preferred to work in the public sector and 31 percent for an NGO, whereas 48 percent of medical students preferred to work for an NGO than in the public sector (31 percent) in the long term. Career growth, opportunities for further training, and salary levels are key factors contributing to HRH attrition from the public to the private sector (MOH, 2011a). A study of comparative salaries in public and private sectors issued by the Ministry of Public Service and Labour in 2007 (amended in 2008) captures the historical reality of higher salaries in the private sector at all levels of the health workforce (MIFOTRA, 2007).

The guidelines for determining salaries in the public sector in Rwanda have evolved over time; starting in 2006 the shift has been toward a system in which salary amounts are attached to the requirements of a specific position (in terms of responsibility and decision making, knowledge and experience, skills, and working environment) rather than to the qualifications of the employee who occupies a position (MIFOTRA, 2012; Vujicic et al., 2009; World Bank, 2018). As a result, the job level for every position is established through objectively based job analysis, evaluation, and classification, and everyone who holds an equivalent position should have the same base salary (Vujicic et al., 2009). The intended outcome of this standardization is to “reduce variability in wages among employees occupying posts of the same level” (Vujicic et al., 2009). In addition to a basic salary, monetary allowances exist that are “associated with the normal duties, responsibilities and requirements of a job, transportation, housing and nonperformance bonuses or payments” (MIFOTRA, 2012). Of note, “in the health sector, allowances have been used historically to circumvent the base salaries in the civil service. In [this] sector, new housing allowances and loans that target doctors who fulfill a set of criteria have been introduced” (Vujicic et al., 2009).

Mobility and Migration in a Regional and Global Health Labor Market

As the nature of health-related issues in the region increasingly calls for cross-border coordination and partnerships, Africa has seen a growing trend toward regionalism in its health sector. The entire continent faces a shortage of health workers, gaps in service coverage, high rates of attrition, and migration of skilled personnel to more favorable work environments (USAID, 2014). Thus, in addition to the internal distribution of the workforce, another key issue contributing to the shortage of HRH in Rwanda is emigration. On a continent already dealing with a high burden of disease and low volume of health care personnel (Chen et al., 2012), as many as “47 [sub-Saharan African] countries have lost more than 60 percent of their doctor workforce to migration” (Greysen et al., 2011). More than 30 percent of locally trained doctors migrate in half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Kasper and Bajunirwe, 2012).

Poppe and colleagues interviewed 27 health professionals (doctors, nurses, and medical assistants) who originated from a wide range of countries, four of whom were from Rwanda, and found three primary reasons for emigrating out of the country: for educational purposes, for political instability and insecurity, and for family reunification (Poppe et al., 2014). Scheffler and colleagues additionally describe congruent categories as motives to immigrate, noting financial motivations, professional development concerns, and personal and family reasons. African doctors migrating to higher-income countries cite being surrounded by accomplished and motivated colleagues as an advantage that creates knowledge spillovers, increased productivity, and greater job satisfaction (Scheffler et al., 2016). Another factor that incentivizes migration is working in a low-resource, high disease burden environment in comparison to their counterparts in high-income countries (Ghebreyesus et al., 2013).

Recognizing the challenge of migration, effective regional coordination in Africa—among economic communities, networks, associations, and technical organizations as well as donors, governments, and implementing partners—will enable African countries to maximize their collective impact in each country sustaining a strong national health workforce and accelerating progress toward improved health and economic outcomes (USAID, 2016). For example, Kenya has bilateral agreements with Rwanda, Namibia, and Lesotho for collaborative health workforce training and the promotion of circular migration of health workers (Taylor et al., 2011).

Health Worker Retention

A notable emphasis of the HRH Program was to address low recruitment for residencies by increasing students' exposure to certain specialties during undergraduate medical training and by providing mentorship. In a 2018 gender-based analysis of factors that affected selection of specialties, surgery was preferable for 46.9 percent of male medical students, and obstetrics and gynecology for 29.4 percent of females. Although female medical students were less likely than their male counterparts to pursue surgery as their first option, females were more likely to join surgery, based on perceived research opportunities, and males were more likely to drop the selection of surgery as a specialty when an adverse interaction with a resident was encountered. Medical students were more likely to consider surgical careers when exposed to positive clerkship experiences that provide intellectual challenges, as well as focused mentorship that facilitates effective research opportunities (Kansayisa et al., 2018). Factors influencing the lack of selection for the anesthesia program included long work hours and high stress level, insufficient mentorship, and low job opportunity (Chan et al., 2016).

The requirement to serve in a district hospital for 2 years was recognized as a deterrent to postgraduate recruitment, particularly for women; the MOH proposed waiving that requirement for female physicians as an incentive, among other strategies that aimed to make medical training more compatible with Rwandan cultural practices (MOH, 2011b). However, the MOH did require a “bonding period” for all new graduates under the HRH Program: In return for tuition coverage, graduates were expected to remain in Rwanda and commit to working in the public sector for 4 to 5 years (Cancedda et al., 2018). According to the University of Rwanda, the MOH provided different levels of tuition support to students through the HRH Program: between 34 and 48 percent of tuition for medical students (undergraduate and postgraduate); 100 percent tuition for MHA students from 2013 to 2017; 0 percent tuition for MHA students from 2018 to 2019; and 100 percent tuition for nursing students from 2016 to 2019.

Government of Rwanda policies were seen as the key mechanisms for retaining HRH Program trainees. Respondents' most frequently cited policy was the government's bonding period. The consequences for not fulfilling the bonding period were unclear, although one government document states that “failure to remain in the service would result in … refunding all or a portion of the training cost to the Government” (MIFOTRA, 2012). The Wage Bill states that “it is unclear what sanctions are for defaulters, or if any have been implemented” (World Bank, 2008). Health workers who pursued education outside of the country were also committed to a bonding period, although the requirement was 3 years, upon their return to Rwanda.

HRH trainees did see the bonding period as positively affecting the retention of graduates:

In our class, for example, we were 14. All of us are still working in public institutions, because in our contract we sign at the end of training…. No one is working in a private clinic. We are all in public institutions where the Ministry of Health has placed us. (86, University of Rwanda Faculty and Former Student in Pediatrics)

However, respondents also reported that long-term retention of HRH trainees was impossible to predict, due to the early timing of this evaluation relative to HRH trainee bonding periods:

I don't know much about the longer-term retention that it will have on the public health system…. There aren't a ton who have truly finished their payback time. They are increasing the pool. I think the retention will be a longer-term question. (12, International NGO Representative)

Some respondents made the link to broader HIV-prevention goals, even in the discussion of retaining health workers in the Rwandan public health system as an HRH Program goal. As one respondent representing a professional association stated,

[I]f you are an HIV-trained person [and] you leave Rwanda to go working in Tanzania, Burundi, or Kenya, you are still taking care of HIV patients, you are dropping down the risk of transmission … which is the goal of [PEPFAR] funding anyway. (35, University of Rwanda Non-Twinned Faculty and Professional Association Representative in Internal Medicine)

Program administration respondents viewed the MOH as providing a work environment that would increase health workers' job satisfaction and thus improve retention. This environment included regularly paid and acceptable salaries,3 opportunities for career progression, and equipment necessary to provide health care services, which had an interactive effect with increased health worker skills produced through the HRH Program:

There are two parts of retention, one is to increase the salary. I have heard there was some salary increase. The second part of it was with buying equipment, so there is this job satisfaction. You have better trained nurses, you have better equipment, so now you are doing your job [with] satisfaction. (45, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

There is that … career progression structure which is now implemented to assess movements upwards of different doctors [and] strong professional bodies that keep developing capacity and meet the requirements to move upwards. (43, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

In contrast, representatives from professional associations expressed that weak infrastructure, including equipment, posed a challenge to health worker retention, particularly at lower-level facilities:

[I]n a district hospital … it is regular to not have what you need, it is chronic and it is very frustrating and you don't want to stay there and you go wherever because it is a huge frustration. (10, Professional Association Representative in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

Similarly, U.S. institution (USI) faculty felt that the low salaries, as compared to private or NGO positions, pulled health workers out of the public system:

[T]hey have departed for NGOs within Africa in conflict or humanitarian zones. They get paid $5,000 a month rather than $1,000 a month. (83, USI Twinned Faculty in Surgery)

Respondents also noted that some MOH policies and practices impaired retention. Notably, blanket retention policies were seen as a hindrance, regardless of urban or rural location of the job posting, in line with the literature:

The same staff retention policy that we apply in Kigali would be completely different from health facilities very far away, where you find social services are very limited, the milieu of work is really inappropriate. But in design, you didn't find specific activities that are specific to areas, then you end up benefitting some areas but not others. (04, Other Donor Representative)

Respondents described the MOH practice of moving health workers from one facility to the next as “disruptive” (05, International NGO Representative), especially for staff with families; the practice also prompted health workers to seek opportunities outside the public health system.

UPGRADING AND PROCURING EQUIPMENT

Across the region, issues of infrastructure permeate health professional education. A literature review of medical education in sub-Saharan Africa cited infrastructure as a common challenge due to the “inadequacy of overall funding to maintain or update facilities as well as the insufficiency of staff resources for teaching and administration” (Greysen et al., 2011). Additionally, “the quantity and quality of a number of resources—student and teaching resources, technology, and clinical teaching sites—were perceived by respondents on average to be below adequate” (Chen et al., 2012). Chen and colleagues (2012) also write:

Medical schools report inadequacies in a number of key physical resource areas, including skills and research labs, journals, student residences, and computers.… The most significant reported barriers to improving quality and increasing graduate numbers are insufficient physical infrastructure (labs, computers, teaching resources, and libraries) and faculty shortages.

In fact, physical infrastructure was included as one of the “greatest needs for medical schools” (Chen et al., 2012).

Enhancing education-related infrastructure and equipment in health facilities and educational sites was a critical challenge to address within the HRH Program to facilitate improved health professional education and its sustainability (MOH, 2014b). With a total budget of $151.8 million for the 8-year project period, $29.8 million was projected for infrastructure and equipment upgrades under the line item “Rwandan Schools” (MOH, 2011b). Of that projected budget, $1.5 million was allocated for equipment maintenance. The 2014 monitoring and evaluation (M&E) plan cited two key output indicators for semiannual monitoring: (1) number of newly procured equipment and installed at site level, and (2) number of staff trained on equipment maintenance (MOH, 2014b).

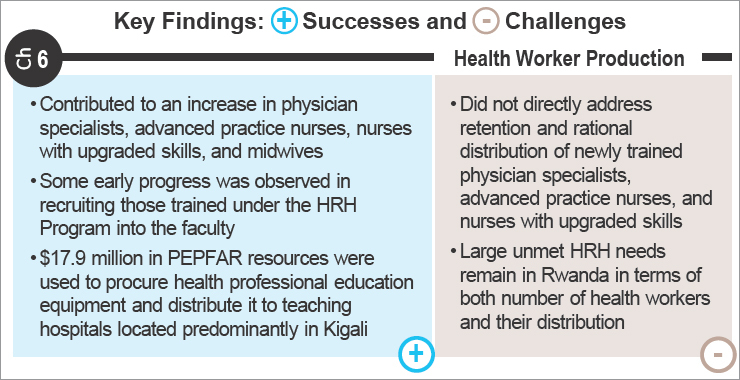

According to MOH records, President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)-supported HRH Program expenditures totaled $59.1 million, including $17.9 million on health professional education-related equipment procurement, almost $2 million more than the $16.1 million budgeted for equipment. Equipment procured with PEPFAR funds included a range of items: teaching and reference books, thermometers and stethoscopes, teaching simulators, and larger equipment for clinical services, such as echocardiograph machines and portable blood testing machines. Equipment primarily went to facilities in 24 of Rwanda's 30 districts (see Figure 6-6), with the largest portion going to Nyarugenge District (see Table 6-5), specifically to CHUK, the country's largest teaching hospital (see Table 6-6). Huye District and CHUB, another large teaching hospital and the previous site of Rwanda's medical school, received the second largest amounts of equipment.

FIGURE 6-6

Distribution of sites receiving health professional education equipment through PEPFAR support under the HRH Program by district.

One HRH Program administrator from the Government of Rwanda described equipment as a component in the M&E plan; however, no such details were actually included. The financial sustainability of the HRH Program assumed 5 percent growth in the Government of Rwanda's budget and commitment to increased health-sector spending to meet Abuja Declaration targets estimated at $54.5 million, which would presumably include equipment maintenance costs (MOH, 2011b). Donor restrictions in what the HRH Program could fund were highlighted in the 2016 midterm review. Necessary infrastructure and medical equipment investments outlined in the funding proposal could not be funded, affecting planned hospital upgrades and development of new training programs such as dentistry4 (MOH, 2016). Challenges with procurement processes were also cited by respondents. The midterm review recommended improvements in infrastructure and equipment deficiencies as well as procurement delays moving forward. Non-Rwandan respondents noted similar challenges within the context of this evaluation.

Rwandan respondents reported that equipment was procured under the HRH Program, while non-Rwandan respondents were largely skeptical about whether teaching sites actually received such equipment. Government of Rwanda HRH Program administrators reported positive achievements in the increased procurement of equipment to fill gaps at the health facilities (e.g., ultrasound machines, autoclaves, anesthesia machines, pediatric monitors, radiotherapy and other heavy equipment, equipment to facilitate training at the simulation center, wireless Internet connections, computers, and other similar devices). One respondent from this stakeholder group stated:

The Program equipped the teaching site from the schools to the hospitals with innovative equipment. To equip them with wireless [equipment] … to upgrade their online library, buying some mannequins for simulation, constructing for simulation labs, and some heavy equipment. Even radiotherapy, they helped to buy a radiotherapy [device]. Even a cancer center, which is under building now. Not only that, for the nursing school which was upgraded, there was a simulation lab, a library with books, Internet connection, videoconference, even tablets for them to really access online courses. All these really have been achieved from the support of the HRH Program. (03, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

TABLE 6-5Equipment by District Procured with PEPFAR Support Under the HRH Program, 2013–2017

| District | Number of Sites Receiving Equipment | Number of Pieces of Equipment* | Value of Equipment (U.S. Dollars)** | Percentage of Total Equipment Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyarugenge | 5 | 1,797 | $4,436,711 | 27.6 |

| Huye | 3 | 1,031 | $3,366,489 | 20.9 |

| Kicukiro | 2 | 299 | $1,313,672 | 8.2 |

| Ngoma | 2 | 172 | $1,215,297 | 7.6 |

| Karongi | 2 | 84 | $959,520 | 6.0 |

| Gasabo | 2 | 376 | $902,598 | 5.6 |

| Rwamagana | 2 | 120 | $571,644 | 3.6 |

| Nyamasheke | 3 | 131 | $365,803 | 2.3 |

| Musanze | 2 | 31 | $302,082 | 1.9 |

| Rutsiro | 1 | 22 | $281,986 | 1.8 |

| Rusizi | 1 | 17 | $279,700 | 1.7 |

| Nyabihu | 1 | 15 | $270,865 | 1.7 |

| Nyanza | 1 | 15 | $232,281 | 1.4 |

| Ruhango | 2 | 79 | $232,169 | 1.4 |

| Kayonza | 1 | 14 | $227,894 | 1.4 |

| Rubavu | 3 | 203 | $210,564 | 1.3 |

| Muhanga | 1 | 121 | $156,895 | 1.0 |

| Gakenke | 2 | 9 | $151,393 | 0.9 |

| Rulindo | 1 | 10 | $143,965 | 0.9 |

| Ngororero | 2 | 8 | $125,057 | 0.8 |

| Nyagatare | 1 | 15 | $91,280 | 0.6 |

| Kamonyi | 2 | 89 | $86,193 | 0.5 |

| Gicumbi | 1 | 21 | $84,418 | 0.5 |

| Gatsibo | 1 | 1 | $43,590 | 0.3 |

| Bugesera | 1 | 1 | $16,169 | 0.1 |

| Total | 46 | 4,709 | $16,083,568 | 100 |

- *

Includes items ranging in value from books and printed job aids to computerized tomography scanners.

- **

13 (0.3 percent) of the pieces of equipment were missing a value in the database, including high-priced equipment such as backup generators.

SOURCE: HRH Program Equipment Master List provided by the MOH.

TABLE 6-6Equipment by Site Procured with PEPFAR Support Under the HRH Program, 2013–2017

| Site | Number of Pieces of Equipment* | Value of Equipment (U.S. Dollars) | Percentage of Total Equipment Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHUK | 1,138 | $4,020,767 | 25.0 |

| CHUB | 996 | $3,127,022 | 19.4 |

| RMH | 242 | $1,312,212 | 8.2 |

| Kibungo | 48 | $1,197,401 | 7.4 |

| Kibuye | 81 | $928,974 | 5.8 |

| King Faisal Hospital | 364 | $802,954 | 5.0 |

| Rwamagana | 71 | $539,005 | 3.4 |

| All other sites (38) | 1,769 | $4,155,082 | 25.8 |

| Total | 4,709 | $16,083,568 | 100 |

NOTE: CHUB = Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Butare/University Teaching Hospital, Butare; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Kigali/CHUK = University Teaching Hospital, Kigali; RMH = Rwanda Military Hospital.

- *

Includes items ranging in value from books and printed job aids to computerized tomography scanners.

SOURCE: HRH Program Equipment Master List provided by the MOH.

Procurement data provided by the MOH demonstrate that the equipment with the greatest value was for radiology, while the greatest number of pieces of equipment purchased went to internal medicine as well as critical care and surgery. More sites received equipment for obstetrics and gynecology than other specialties (see Table 6-7).

Given that many of the resources went to purchasing equipment for tertiary care, it is understandable that the geographic distribution was weighted more toward urban locations, where tertiary care hospitals are located.

TABLE 6-7Types of Equipment Procured with PEPFAR Support Under the HRH Program, 2013–2017

| Type | Number of Sites Receiving Equipment | Number of Pieces of Equipment* | Value of Equipment (U.S. Dollars) | Percentage of Total Equipment Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiology | 15 | 32 | $4,242,599 | 26.4 |

| Internal Medicine and Critical Care** | 32 | 1,404 | $3,858,533 | 24.0 |

| Surgery*** | 30 | 612 | $3,755,514 | 23.4 |

| Any or Unclear Purpose**** | 31 | 402 | $1,245,445 | 7.7 |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 34 | 653 | $1,001,418 | 6.2 |

| Pediatrics***** | 11 | 294 | $481,128 | 3.0 |

| Clinical Teaching****** | 12 | 151 | $423,717 | 2.6 |

| Patient Care | 16 | 150 | $366,217 | 2.3 |

| Laboratory | 6 | 19 | $222,464 | 1.4 |

| Nursing | 12 | 88 | $216,267 | 1.3 |

| Book | 12 | 627 | $143,946 | 0.9 |

| Teaching Facility | 1 | 123 | $71,720 | 0.4 |

| Patient Room******* | 10 | 154 | $54,600 | 0.3 |

| Total | 44 | 4,709 | $16,083,568 | 100 |

NOTE: Categorizing equipment by specialty is challenging as some equipment can be used for multiple purposes.

- *

Includes items ranging in value from books and printed job aids to computerized tomography scanners.

- **

Includes internal medicine; critical care; anesthesia; emergency medicine; trauma; cardiology; gastroenterology; hematology; nephrology; ophthalmology; neurology; ear, nose, and throat; pulmonary; and surgery.

- ***

Includes surgery, plastics, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedics, neurosurgery, and urology.

- ****

Includes items that can be used for multiple purposes such as thermometers and scales, and general purposes such as generators.

- *****

Includes items for pediatrics, pediatric critical care, pediatric anesthesia, and pediatric emergency medicine.

- ******

Includes clinical teaching for internal medicine, surgery, critical care, anesthesia, emergency medicine, urology, nursing, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and gastroenterology.

- *******

Includes wall clocks that may have been used for patient rooms or teaching facilities.

SOURCE: HRH Program Equipment Master List provided by the MOH.

HRH trainees generally agreed that equipment had been procured, and reported improvements in infrastructure, such as access to research websites and educational materials; ultrasound machines; ear, nose, and throat materials; high-fidelity mannequins; new centers of excellence; and simulation labs. University of Rwanda administrators reported new e-learning programs, fiber-optic Internet, books, and subscriptions to journals. Nonetheless, HRH trainees reported that needs remained, and that some of the infrastructure the HRH Program had provided did not match their skill sets. An HRH Program administrator in the Government of Rwanda and a former HRH trainee further noted that training in equipment use and maintenance was lacking or a challenge. Almost all respondents reported that it was unclear which procurements were supported through the HRH Program or were unable to specifically link discrete procurements to the Program.

Non-Rwandan respondents reported skepticism on equipment procurement, citing that requests were changed or not delivered and that projected funds for procurement did not fund what they were intended to, or reported defensiveness from the MOH. One respondent supplemented procurement from Partners In Health funds. Specifically, for HIV, a donor agency respondent commented that her organization had procured equipment and other commodities for HIV service delivery. However, equipment was still viewed as missing or insufficient.

CONCLUSIONS

The HRH Program succeeded in expanding Rwanda's health workforce, with particular success in increasing the qualifications of nurses (both general and specialty) and increasing the number of physician specialists. The number of specialist physicians grew from 150 in 2011 to 567 in 2018, surpassing the HRH Program target of 551 (MOH, 2011b). It is important to note that the considerable gains in the number of specialists in Rwanda have not come at the expense of the number of general practitioners, which also increased. Although the targeted numbers of general practitioners and the targeted number of nurses and midwives were not reached, both have increased by 10 percent on a per-population basis since 2011. Also, while the absolute number of nurses fell short of the HRH Program target, the qualifications of nurses increased considerably, with 111 nurses graduating with specialty qualifications in the first cohort. According to the Master Facility List, there were 5,676 practicing A1 and A0 nurses in Rwanda in 2018 (MOH, 2018b). In 2011, there were 104 practicing nurses and midwives with bachelor's credentials and 797 with advanced diploma credentials according to the HRH Program midterm review (MOH, 2016).

More health workers, physician specialists, nurses, and midwives were produced but there is still an unmet need. Rwanda continues to lag well behind the WHO recommended 44.5 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population with only 10.5 per 10,000 population. The country's HSSP IV targets call for increasing the health workforce to 15 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population by 2024 (MOH, 2018a). This continued shortage poses a major bottleneck for the population of 10 million Rwandans seeking health services, with implications on their health outcomes.

Furthermore, distribution of health workers throughout the country remains inequitable. The geographic imbalances in the distribution of qualified health workers is exacerbated by those who favor urban areas, preference of workers for the private sector, and low levels of motivation and performance in the public sector (Lievens et al., 2010). Although some physician specialists have begun working at the district hospital level, the vast majority are concentrated in 4 of Rwanda's 30 districts (Gasabo, Huye, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge). Likewise, the numbers of general practitioners, nurses, and midwives vary considerably. Five districts exceed the HSSP IV target of 1 doctor per 7,000 population, while 18 districts have fewer than 1 doctor per 15,000 population (MOH, 2018a). Four districts exceed the HSSP IV target of 1 nurse per 800 population, while 10 districts have fewer than 1 nurse per 2,000 population.

Retention strategies for trainees once they were placed into practice were outside the scope of the HRH Program; these strategies relied mainly on the government-established bonding mechanism, with limited approaches to bolster retention beyond this. Although graduates did work in the public health system, in large part due to the bonding scheme, the long-term impact on retention remains unclear, due to the timing of this evaluation. Retention in both Rwanda and in underserved areas is important to address. The availability of supplies and equipment, especially in remote and rural areas, is key to retaining health workers and promoting productivity and performance. In Ghana, for example, midwives cite several motivating factors for working in a rural area: having time off for training after 2 years of rural service; an acceptable work environment that includes a reliable supply of medications, electricity, and appropriate technology; and adequate housing. In Nigeria, inadequate facilities and medication supplies, poor management of the public health sector, and primitive living conditions affect retention of rural health workers (Awofeso, 2010), with midwives citing poor job satisfaction, low salaries, and lack of career opportunities (Adegoke et al., 2015).

Multiple studies have found decreased risk of emigration of health workers from low- and middle-income countries with expanded in-country specialty training, opportunities for research, and partnerships with universities that can offer research and leadership training. In-country training of physician specialists has been shown to improve retention, with 87 percent to 97 percent of surgeons trained at the Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons from 2003 to 2016 remaining in Ghana (Gyedu et al., 2019). In the 25 institutions that train surgeons in the 10 countries that are covered by the College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA), 85.1 percent of 1,038 graduates from 1974 to 2013 stayed in the country of training, 88.3 percent stayed in the COSECSA region, and 93.4 percent stayed in Africa (Hutch et al., 2017).

Despite the increase in health workers and the upgrading of skills, there was a tension between the perceived need for specialized care and advanced practice skills and the perceived need for more general practice and primary care. The Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, reiterated in 2018, identified primary health care as pivotal to attaining the goal of health for all. Although significant advances have been made in primary health care, including health benefits across the social gradient, many have drifted away in preference for specific vertical health care programs (WHO, 1978, 2008). The tension between primary and specialist care can be further compounded by systems of financing. The payment policies in some insurance-based financing favor specialized services, while in some cases efforts to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) can increase the demand for primary care by reducing the financial burden for those seeking such care (Rao and Pilot, 2014).5

Rwanda's movement toward UHC is often cited as an example of success. Rwanda is continuing to make progress toward improved access to and use of health care through community-based health insurance and performance-based financing. Both options emphasize primary and preventive care, contributing to the envisioned Alma Ata Declaration with positive effects on the use of health care services such as curative care visits, institutional deliveries, antenatal care, or child health care (Collins et al., 2016; Rusa et al., 2009). The annual per capita use rate for community-based health insurance members surpassed the WHO recommended average of 1.0 visit, with 1.23 visits at the health center level and 0.18 at the district hospital level in 2012 and 2013. This was a marked increase from the 0.25 visits recorded in 1999 (Kalisa et al., 2016).

A specialty care model, when implemented successfully, can also expand access to care and care delivery through the implementation of management systems that emphasize standardization and continuous improvement, attracting and training of a specialized health workforce, access to equipment and low-cost technologies, and generation of patient volume (Bhandari et al., 2008). The growth of specialization in graduate medical education and physician practice has had an effect on physician workforce composition, contributing to a shortage in general practitioners. However, there is also a shortage of and critical need for specialized physicians, and the distribution of specialists is often imbalanced (Hoyler et al., 2014). Allowing nurses and midwives to practice to full scope can save lives and improve health outcomes, as has been noted for HIV and improved mother and baby outcomes (Colvin et al., 2010; Dohrn et al., 2009; Fairall et al., 2012; Iwu and Holzemer, 2014; Lancet Series on Midwifery Executive Group, 2014; Sanne et al., 2010).

Rwanda's pursuit of specialized physician care and upgraded nursing practice in some ways combined elements of both schools of thought (vertical/specialty versus horizontal/primary). Whether the balance was right, and can be maintained, remains to be seen. The concurrent role of CHWs and their support by health professionals was unaddressed in the HRH Program.

REFERENCES

- Adegoke AA, Atiyaye FB, Abubakar AS, Auta A, Aboda A. Job satisfaction and retention of midwives in rural Nigeria. Midwifery. 2015;31(10):946–956. [PubMed: 26144368]

- Ageyi-Baffour P, Rominski S, Nakua E, Gyakobo M, Lori JR. Factors that influence midwifery students in Ghana when deciding where to practice: A discrete choice experiment. BMC Medical Education. 2013;13:64. [PMC free article: PMC3684532] [PubMed: 23642076]

- Alleyne G. Lessons and leadership in health comment on “improving the world's health through the post-2015 development agenda: Perspectives from Rwanda.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2015;4(8):553–555. [PMC free article: PMC4529048] [PubMed: 26340398]

- Asongu SA. The impact of health worker migration on development dynamics: Evidence of wealth effects from Africa. European Journal of Health and Economics. 2014;15(2):187–201. [PubMed: 23460479]

- Awofeso N. Improving health workforce recruitment and retention in rural and remote regions of Nigeria. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(1):1319. [PubMed: 20136347]

- Bhandari A, Dratler S, Raube K, Thulasiraj RD. Specialty care systems: A pioneering vision for global health. Health Affairs. 2008;27(4):964–976. [PubMed: 18607029]

- Binagwaho A, Wagner CM, Gatera M, Karema C, Nutt CT, Ngabo F. Achieving high coverage in Rwanda's national human papillomavirus vaccination programme. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(8):623–628. [PMC free article: PMC3417784] [PubMed: 22893746]

- Cancedda C, Binagwaho A. The Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda: A response to recent commentaries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2019;8(7):459–461. [PMC free article: PMC6706974] [PubMed: 31441284]

- Cancedda C, Cotton P, Shema J, Rulisa S, Riviello R, Adams LV, Farmer PE, Kagwiza JN, Kyamanywa P, Mukamana D, Mumena C, Tumusiime DK, Mukashyaka L, Ndenga E, Twagirumugabe T, Mukara KB, Dusabejambo V, Walker TD, Nkusi E, Bazzett-Matabele L, Butera A, Rugwizangoga B, Kabayiza JC, Kanyandekwe S, Kalisa L, Ntirenganya F, Dixson J, Rogo T, McCall N, Corden M, Wong R, Mukeshimana M, Gatarayiha A, Ntagungira EK, Yaman A, Musabeyezu J, Sliney A, Nuthulaganti T, Kernan M, Okwi P, Rhatigan J, Barrow J, Wilson K, Levine AC, Reece R, Koster M, Moresky RT, O'Flaherty JE, Palumbo PE, Ginwalla R, Binanay CA, Thielman N, Relf M, Wright R, Hill M, Chyun D, Klar RT, McCreary LL, Hughes TL, Moen M, Meeks V, Barrows B, Durieux ME, McClain CD, Bunts A, Calland FJ, Hedt-Gauthier B, Milner D, Raviola G, Smith SE, Tuteja M, Magriples U, Rastegar A, Arnold L, Magaziner I, Binagwaho A. Health professional training and capacity strengthening through international academic partnerships: The first five years of the Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2018;7(11):1024–1039. [PMC free article: PMC6326644] [PubMed: 30624876]

- Chan DM, Wong R, Runnels S, Muhizi E, McClain CD. Factors influencing the choice of anesthesia as a career by undergraduates of the University of Rwanda. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2016;123(2):481–487. [PubMed: 27308955]

- Chen C, Buch E, Wassermann T, Frehywot S, Mullan F, Omaswa F, Greysen SR, Kolars JC, Dovlo D, El Gali Abu Bakr DE, Haileamlak A, Koumare AK, Olapade-Olaopa EO. A survey of sub-Saharan African medical schools. Human Resources for Health. 2012;10:4. [PMC free article: PMC3311571] [PubMed: 22364206]

- Collins D, Saya U, Kunda T. The impact of community-based health insurance on access to care and equity in Rwanda. Medford, MA: Management Sciences for Health; 2016.

- Colvin CJ, Fairall L, Lewin S, Georgeu D, Zwarenstein M, Bachmann MO, Uebel KE, Bateman ED. Expanding access to ART in South Africa: The role of nurse-initiated treatment. South Africa Medical Journal. 2010;100(4):210–212. [PubMed: 20459957]

- Condo J, Mugeni C, Naughton B, Hall K, Tuazon MA, Omwega A, Nwaigwe F, Drobac P, Hyder Z, Ngabo F, Binagwaho A. Rwanda's evolving community health worker system: A qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Human Resources for Health. 2014;12:71. [PMC free article: PMC4320528] [PubMed: 25495237]

- Davies J, Vreede E, Onajin-Obembe B, Morriss W. What is the minimum number of specialist anaesthetists needed in low-income and middle-income countries? BMJ Global Health. 2018;3:e001005. [PMC free article: PMC6278919] [PubMed: 30588342]

- Dohrn J, Nzama B, Murrman M. The impact of HIV scale-up on the role of nurses in South Africa: Time for a new approach. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2009;52(Suppl 1):S27–S29. [PubMed: 19858933]

- Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, Timmerman V, Uebel K, Zwarenstein M, Boulle A, Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, Faris G, Cornick R, Draper B, Tshabalala M, Kotze E, van Vuuren C, Steyn D, Chapman R, Bateman E. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): A pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):889–898. [PMC free article: PMC3442223] [PubMed: 22901955]

- Ghebreyesus TA, Sheffler RM, Soucat ALB. Labor market for health workers in Africa : New look at the crisis. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013.

- Greysen SR, Dovlo D, Olapade-Olaopa EO, Jacobs M, Sewankambo N, Mullan F. Medical education in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. Medical Education. 2011;45(10):973–986. [PubMed: 21916938]

- Gyedu A, Debrah S, Agbedinu K, Goodman SK, Plange-Rhule J, Donkor P, Mock C. In-country training by the Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons: An initiative that has aided surgeon retention and distribution in Ghana. World Journal of Surgery. 2019;43(3):723–735. [PMC free article: PMC6359947] [PubMed: 30386914]

- Hoyler M, Finlayson SR, McClain CD, Meara JG, Hagander L. Shortage of doctors, shortage of data: A review of the global surgery, obstetrics, and anesthesia workforce literature. World Journal of Surgery. 2014;38(2):269–280. [PubMed: 24218153]

- Hutch A, Bekele A, O'Flynn E, Ndonga A, Tierney S, Fualal J, Samkange C, Erzingatsian K. The brain drain myth: Retention of specialist surgical graduates in East, Central and Southern Africa, 1974–2013. World Journal of Surgery. 2017;41(12):3046–3053. [PubMed: 29038829]

- Iwu EN, Holzemer WL. Task shifting of HIV management from doctors to nurses in Africa: Clinical outcomes and evidence on nurse self-efficacy and job satisfaction. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):42–52. [PubMed: 23701374]

- Iyer HS, Hirschhorn LR, Nisingizwe MP, Kamanzi E, Drobac PC, Rwabukwisi FC, Law MR, Muhire A, Rusanganwa V, Basinga P. Impact of a district-wide health center strengthening intervention on healthcare utilization in rural Rwanda: Use of interrupted time series analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182418. [PMC free article: PMC5538651] [PubMed: 28763505]

- Kalisa I, Musange S, Saya U, Kunda T, Collins D. The development of community-based health insurance in Rwanda: Experiences and lessons technical brief. Medford, MA: University of Rwanda and Management Sciences for Health; 2016.

- Kansayisa G, Yi S, Lin Y, Costas-Chavarri A. Gender-based analysis of factors affecting junior medical students' career selection: Addressing the shortage of surgical workforce in Rwanda. Human Resources for Health. 2018;16(1):29. [PMC free article: PMC6042316] [PubMed: 29996860]

- Kasper J, Bajunirwe F. Brain drain in sub-Saharan Africa: Contributing factors, potential remedies and the role of academic medical centres. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012;97(11):973–979. [PubMed: 22962319]

- Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Mercer H, Evans DB. The health worker shortage in Africa: Are enough physicians and nurses being trained? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87(3):225–230. [PMC free article: PMC2654639] [PubMed: 19377719]

- Lancet Series on Midwifery Executive Group. The Lancet series on midwifery. Lancet. 2014;384(9948)

- Lievens T, Serneels P. Synthesis of focus group discussions with health workers in Rwanda. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006.

- Lievens T, Serneels P, Butera JD, Soucat A. Diversity in career preferences of future health workers in Rwanda: Where, why, and for how much? Washington, DC: World Bank; 2010.

- LSTM (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine). Comprehensive evaluation of the community health program in Rwanda final report. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine Centre for Maternal and Newborn Health; 2016.

- MIFOTRA (Ministry of Public Service and Labour). Comparative study for salaries in public and private sectors. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Public Service and Labour; 2007.

- MIFOTRA. Rwanda public sector pay and retention policy and implementation strategy. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Public Service and Labour; 2012.

- MOH (Ministry of Health). Health sector strategic plan, July 2009-June 2012. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2009a.

- MOH. National strategic plan on HIV and AIDS, 2009–2012. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2009b.

- MOH. Rwanda health statistics. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2010.

- MOH. Human Resources for Health strategic plan, 2011–2016. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2011a.

- MOH. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program, 2011–2019: Funding proposal. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2011b.

- MOH. Annual statistics booklet. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2012a.

- MOH. Third health sector strategic plan, July 2012–June 2018. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2012b.

- MOH. Annual report: July 2012-June 2013. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2013a.

- MOH. National community health strategic plan: July 2013–June 2018. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2013b.

- MOH. Rwanda HIV and AIDS national strategic plan: July 2013–June 2018. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2013c.

- MOH. Rwanda annual health statistics booklet 2014. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2014a.

- MOH. Human Resources for Health monitoring & evaluation plan, March. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2014b. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Records Access Office [paro@nas

.edu] or via https://www8 .nationalacademies .org/pa/managerequest .aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08. - MOH. Annual health statistics booklet 2015. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2015.

- MOH. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program midterm review report (2012–2016). Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2016. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Records Access Office [paro@nas

.edu] or via https://www8 .nationalacademies .org/pa/managerequest .aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08. - MOH. Fourth Health Sector Strategic Plan, July 2018–June 2024. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2018a.

- MOH. A report of development of Rwanda master facility list: Final report November. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health; 2018b.

- Mullan F, Frehywot S, Omaswa F, Buch E, Chen C, Greysen SR, Wassermann T, Eldin Elgaili Abubakr D, Awases M, Boelen C, Diomande MJMI, Dovlo D, Ferro J, Haileamlak A, Iputo J, Jacobs M, Koumaré AK, Mipando M, Monekosso GL, Olapade-Olaopa EO, Rugarabamu P, Sewankambo NK, Ross H, Ayas H, Chale SB, Cyprien S, Cohen J, Haile-Mariam T, Hamburger E, Jolley L, Kolars JC, Kombe G, Neusy AJ. Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1113–1121. [PubMed: 21074256]

- Ngo DKL, Sherry TB, Bauhoff S. Health system changes under pay-for-performance: The effects of Rwanda's national programme on facility inputs. Health Policy and Planning. 2016;32(1):11–20. [PubMed: 27436339]

- NISR (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda). Fourth population and housing census, Rwanda, 2012, thematic report: Labour force participation. Kigali, Rwanda: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda; 2014.

- NISR. Labour force survey annual report, December 2018. Kigali, Rwanda: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda; 2018.

- Nsanzimana S, Prabhu K, McDermott H, Karita E, Forrest JI, Drobac P, Farmer P, Mills EJ, Binagwaho A. Improving health outcomes through concurrent HIV program scale-up and health system development in Rwanda: 20 years of experience. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(1):216. [PMC free article: PMC4564958] [PubMed: 26354601]

- Open Data for Africa. Rwanda data portal: Health profile. Kigali, Rwanda: African Development Bank; 2018.

- Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V, Ntakiyiruta G, Calland F. Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. British Journal of Surgery. 2012;99(3) [PubMed: 22237597]

- Poppe A, Jirovsky E, Blacklock C, Laxmikanth P, Moosa S, De Maeseneer J, Kutalek R, Peersman W. Why sub-Saharan African health workers migrate to European countries that do not actively recruit: A qualitative study post-migration. Global Health Action. 2014;7:24071. [PMC free article: PMC4021817] [PubMed: 24836444]

- Rao M, Pilot E. The missing link—the role of primary care in global health. Global Health Action. 2014;7:23693. [PMC free article: PMC3926992] [PubMed: 24560266]

- RGB (Rwanda Governance Board). Rwanda community health workers programme: 1995–2015; 20 years of building healthier communities. Kigali, Rwanda: Rwanda Governance Board; 2017.

- Rusa L, Ngirabega JDD, Janssen W, Van Bastelaere S, Porignon D, Vandenbulcke W. Performance-based financing for better quality of services in Rwandan health centres: 3-year experience. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2009;14(7):830–837. [PubMed: 19497081]

- Sanne I, Orrell C, Fox MP, Conradie F, Ive P, Zeinecker J, Cornell M, Heiberg C, Ingram C, Panchia R, Rassool M, Gonin R, Stevens W, Truter H, Dehlinger M, van der Horst C, McIntyre J, Wood R. Nurse versus doctor management of HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (CIPRA-SA): A randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):33–40. [PMC free article: PMC3145152] [PubMed: 20557927]

- Scheffler RM, Herbst CH, Lemiere C, Campbell J. Health labor market analyses in low- and middle-income countries: An evidence-based approach. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2016.

- Sekabaraga C, Diop F, Soucat A. Can innovative health financing policies increase access to MDG-related services? Evidence from Rwanda. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 2):ii52–ii62. [PubMed: 22027920]

- Serneels P, Lievens T. Institutions for health care delivery: A formal exploration of what matters to health workers evidence from Rwanda. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2008. [PMC free article: PMC5787262] [PubMed: 29373966]

- Serneels P, Montalvo JG, Pettersson G, Lievens T, Butera JD, Kidanu A. Who wants to work in a rural health post? The role of intrinsic motivation, rural background and faith-based institutions in Ethiopia and Rwanda. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88(5):342–349. [PMC free article: PMC2865659] [PubMed: 20461138]

- Suthar AB, Nagata JM, Nsanzimana S, Bärnighausen T, Negussie EK, Doherty MC. Performance-based financing for improving HIV/AIDS service delivery: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):6. [PMC free article: PMC5210258] [PubMed: 28052771]

- Taylor AL, Hwenda L, Larsen BI, Daulaire N. Stemming the brain drain—a WHO global code of practice on international recruitment of health personnel. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(25):2348–2351. [PubMed: 22187983]

- Thomson S. How Rwanda beats the United States and France in gender equality. 2017. [February 5, 2020]. https://www

.weforum.org /agenda/2017/05/how-rwanda-beats-almost-every-other-country-in-gender-equality. - USAID (United States Agency for International Development). African higher education: Opportunities for transformative change for sustainable development. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development; 2014.

- USAID. East Africa regional development cooperation strategy 2016-2021. Nairobi, Kenya: United States Agency for International Development; 2016.

- Uwizeye G, Mukamana D, Relf M, Rosa W, Kim MJ, Uwimana P, Ewing H, Munyiginya P, Pyburn R, Lubimbi N, Collins A, Soule I, Burke K, Niyokindi J, Moreland P. Building nursing and midwifery capacity through Rwanda's Human Resources for Health Program. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2018;29(2):192–201. [PubMed: 28826335]

- Vujicic M, Ohiri K, Sparkes S. Working in health: Financing and managing the public sector health workforce. Paris, France: World Bank; 2009.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. WHO Chronicle. 1978;32(11):428–430. [PubMed: 11643481]

- WHO. The world health report 2008: Primary health care; now more than ever. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008.

- WHO. Transforming and scaling up health professionals' education and training. 2013. [February 9, 2020]. https://www

.who.int/hrh /resources/transf_scaling_hpet/en. [PubMed: 26042324] - WHO. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [PMC free article: PMC3853967] [PubMed: 24347717]

- World Bank. Beyond Wage Bill ceilings: The impact of government fiscal and human resource management policies on the health workforce in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2008. Background country study for Rwanda.

- World Bank. Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) (modeled ILO estimate). 2018. [October 14, 2019]. https://data

.worldbank .org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS. - Zeng W, Rwiyereka AK, Amico PR, Ávila-Figueroa C, Shepard DS. Efficiency of HIV/AIDS health centers and effect of community-based health insurance and performance-based financing on HIV/AIDS service delivery in Rwanda. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014;90(4):740–746. [PMC free article: PMC3973523] [PubMed: 24515939]

Footnotes

- 1

Shifting health care services to nurses and CHWs has been a key strategy for expanding access to primary care in Rwanda and elsewhere. Cancedda and Binagwaho (2019) point out that the HRH Program was designed to complement existing and ongoing efforts that strengthened primary care, including task shifting.

- 2

There is no singular guidance on the number or density of medical specialists in low- and middle-income countries. In fact, the WHO's Global Health Observatory data repository, which tracks health worker density, does not disaggregate medical specialists at all. A review of the literature revealed little guidance on the topic as well. One recent modeling exercise suggests that four physician anesthesia providers per 100,000 population is a “modest target” (Davies et al., 2018).

- 3

Salaries were set via job classifications, which fell under the purview of the Ministry of Public Service and Labour. At the time of data collection, it was reported that job classifications should have been reviewed in 2017. Salaries were determined based on the position, rather than on “the diploma carried by the person who occupies a position” (Vujicic et al., 2009).

- 4

The development of the dentistry program at the University of Rwanda was not supported by PEPFAR's investments and therefore not included in this evaluation.

- 5

This text has changed since the prepublication release of this report.

- Health Worker Production - Evaluation of PEPFAR's Contribution (2012-2017) to Rw...Health Worker Production - Evaluation of PEPFAR's Contribution (2012-2017) to Rwanda's Human Resources for Health Program

- Enasidenib - LiverToxEnasidenib - LiverTox