All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: tni.ohw@snoissimrep).

… to promote personal mobility and enhance quality of life.

The introduction to the guidelines:

- defines an appropriate wheelchair;

- introduces users;

- points out the needs for and rights to wheelchairs;

- describes the benefits of wheelchairs;

- describes basic types of wheelchair and common systems of wheelchair provision; and

- describes different stakeholders and their roles in wheelchair provision.

Box 1.1Wheelchairs to enhance quality of life …

Testimonial from a user in Afghanistan

Zahida lives in Afghanistan, in a tent in her brother's yard. She became paraplegic in 2001, but has had two children since then. She was referred to a hospital outpatient physiotherapy department in Jalalabad and arrived pushed in a wheelbarrow. The physiotherapists worked with the technicians of a local wheelchair workshop to provide Zahida with a three-wheel wheelchair.

Without a wheelchair, Zahida could do very little at home without the help of her husband and children. She just lay on the bed. Her wheelchair has enabled her to successfully look after her children in a very rough and hilly compound. Zahida says, “My wheelchair – it is like my feet – I won't go anywhere without it! With my wheelchair I can cook, make bread, visit the neighbours. When we go to a family wedding in the village I take it with me in the back of the taxi. My older daughter and son help to push me up the steep places.”

1.1. Appropriate wheelchairs

These guidelines focus on appropriate manual wheelchairs. Manual wheelchairs are here defined as wheelchairs propelled by the user or pushed by another person. A wheelchair is appropriate when it (1):

- meets the user's needs and environmental conditions;

- provides proper fit and postural support;

- is safe and durable;

- is available in the country: and

- can be obtained and maintained and services sustained in the country at an affordable cost.

Throughout these guidelines, the term “wheelchair” means “appropriate manual wheelchair” unless otherwise indicated.

1.2. Users of wheelchairs

In these guidelines, the term “users” refers to people who already use a wheelchair or who can benefit from using a wheelchair because their ability to walk is limited. Users include:

- children, adults and the elderly;

- men and women and girls and boys;

- people with different neuromusculoskeletal impairments, lifestyles, life roles and socioeconomic status; and

- people living in different environments, including rural, semi-urban and urban.

Users represent a wide range of mobility needs, but they have in common the need for a wheelchair to enhance their mobility with dignity.

1.3. Need for wheelchairs

About 10% of the global population, i.e. about 650 million people, have disabilities (2). Studies indicate that, of these, some 10% require a wheelchair. It is thus estimated that about 1% of a total population – or 10% of a disabled population – need wheelchairs, i.e. about 65 million people worldwide.

In 2003, it was estimated that 20 million of those requiring a wheelchair for mobility did not have one. There are indications that only a minority of those in need of wheelchairs have access to them, and of these very few have access to an appropriate wheelchair (1).

1.4. Rights to wheelchairs

States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities have the obligation “to take effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for persons with disabilities”. This is a commitment to provide mobility aids, such as wheelchairs, that make personal mobility possible. In 1993, the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (3) expressed the same commitment, demanding that countries ensure the development, production, distribution and servicing of assistive devices for people with disabilities in order to increase their independence and to realize their human rights.

These two important international declarations create rights to wheelchairs because it is universally recognized that an appropriate wheelchair is a precondition to enjoying equal opportunities and rights, and for securing inclusion and participation. Personal mobility is an essential requirement to participating in many areas of social life, and wheelchairs are for many the best means of guaranteeing personal mobility.

Independent mobility makes it possible for people to study, work, participate in cultural life and access health care. Without wheelchairs, people may be confined to their homes and unable to live a full and inclusive life. We know that eliminating world poverty is not possible unless the needs of those with disabilities are taken into account. Without wheelchairs, these individuals are unable to participate in those mainstream developmental initiatives, programmes and strategies that are targeted to the poor, such as are embodied in the Millennium Development Goals (4), the Poverty Reduction Strategies (5) and other national developmental initiatives.

It is a vicious circle: lacking personal mobility aids, people with disabilities cannot leave the poverty trap. They are more likely to develop secondary complications and become more disabled, and poorer still. If they are children they will be unable to access the educational opportunities available to them, and without an education they will be unable to find employment when they grow up and will be driven even more deeply into poverty.

On the other hand, access to appropriate wheelchairs allows people with disabilities to work and participate in mainstream development initiatives that will reduce their poverty (see Fig.1.1.). Similarly, a wheelchair can enable a child to go to school, to gain an education and, when the time comes, to find a job (see Fig.1.2.).

Fig. 1.1

User at work.

Fig. 1.2

User at school.

The right to a wheelchair must be an essential component of all international endeavours to secure the human rights of people with disabilities.

1.5. Benefits of wheelchairs

Wheelchair provision is not only about the wheelchair, which is just a product (6). Rather, it is about enabling people with disabilities to become mobile, remain healthy and participate fully in community life. A wheelchair is the catalyst to increased independence and social integration, but it is not an end in itself (6–8) (see Fig.1.3.).

Fig.1.3

Participation in community life.

The benefits of using an appropriate wheelchair include those outlined below.

Health and quality of life

In addition to providing mobility, an appropriate wheelchair is of benefit to the physical health and quality of life of the user. Combined with adequate user training, an appropriate wheelchair can serve to reduce common problems such as pressure sores, the progression of deformities or contractures, and other secondary conditions (9). A wheelchair with a proper cushion often prevents premature death in people with spinal cord injuries and similar conditions and, in one sense, is a life-saving device for these people. A wheelchair that is functional, comfortable and can be propelled efficiently can result in increased levels of activity. Independent mobility and increased physical function can reduce dependence on others. Other benefits, such as improved respiration and digestion, increased head, trunk and upper extremity control and overall stability, can be achieved with proper postural support. Maintenance of health is an important factor in measuring quality of life. These factors combined serve to increase access to opportunities for education, employment and participation within the family and the community.

Economy

A wheelchair often makes all the difference between being a passive receiver and an active contributor. Economic benefits are realized when users are able to access opportunities for education and employment. With a wheelchair, an individual can earn a living and contribute to the family's income and national revenue, whereas without a wheelchair that person may remain isolated and be a burden to the family and the nation at large. Similarly, a wheelchair that is not durable will be more expensive owing to the need for frequent repairs, absence from work and eventual replacement of the wheelchair. Providing wheelchairs is more cost-effective if they last longer (10). It is also more cost-effective if users are involved in selecting their devices and if their long-term needs are considered (11).

For society, the financial benefits associated with the provision of wheelchairs include reduced health care expenses, such as those for treating pressure sores and correcting deformities. A study from a developing country reported that in 1997, 75% of those with spinal cord injuries admitted to hospital died within 18–24 months from secondary complications arising from their injuries. In the same place, the incidence of pressure sores decreased by 71% and repetitive urinary tract infections fell by 61% within two years as a result of improvements in health care training and appropriate equipment, including good wheelchairs with cushions (12).

1.6. Challenges for users

Users face a range of challenges, which must be considered when developing approaches to wheelchair provision.

Financial barriers

Some 80% of the people with disabilities in the world live in low-income countries. The majority of them are poor and do not have access to basic services, including rehabilitation facilities (13). The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that the unemployment rates of people with disabilities reach an estimated 80% or more in many developing countries (14). Government funding for the provision of a wheelchair is rarely available, leaving the majority of users unable to pay for a wheelchair themselves.

Physical barriers

As many users are poor, they live in small houses or huts with inaccessible surroundings. They also live where road systems are poor, there is a lack of pavements, and the climate and physical terrain are often extreme. In many contexts, public and private buildings are difficult to access in a wheelchair. These physical barriers place additional requirements on the strength and durability of wheelchairs. They also require that users exercise a high degree of skill if they are to be mobile.

Access to rehabilitation services

In many developing countries, only 3% of people with disabilities who require rehabilitation services have access to them (15). According to a report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur (16), 62 countries have no national rehabilitation services available to people with disabilities. This means that many wheelchair users are at risk of developing secondary complications and premature death that could be avoided with proper rehabilitation services. In many countries, wheelchair service delivery is not included in the national rehabilitation plan.

Education and information

Many users have difficulty in accessing relevant information, such as on their own health conditions, prevention of secondary complications, available rehabilitation services and types of wheelchair available. For many, a wheelchair service may be their first access to any form of rehabilitation service. This places even more emphasis on the importance of user education.

Choice

Users are rarely given the opportunity to choose the most appropriate wheelchair. Often there is only one type of wheelchair available (and often in only one or two sizes), which may not be suited to the user's physical needs, or practical in terms of the user's lifestyle or home or work environment. According to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “States Parties shall take effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for persons with disabilities … by facilitating the personal mobility of persons with disabilities in the manner and at the time of their choice, and at affordable cost” (17).

1.7. Wheelchair provision

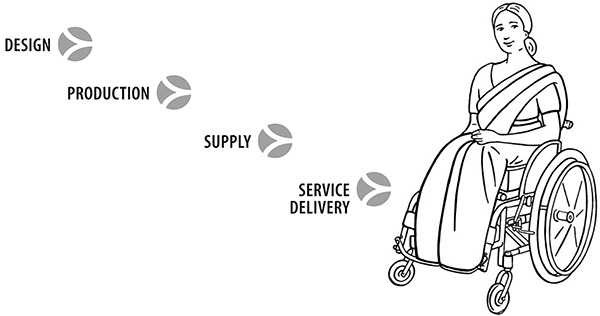

Wheelchair provision usually includes the design, production and supply of wheelchairs and delivery of wheelchair services.

Fig. 1.4Overview of wheelchair provision

Wheelchair provision can only enhance a wheelchair user's quality of life if all parts of the process are working well. This includes ensuring users have access to:

- wheelchairs of an appropriate design;

- wheelchairs that have been produced to appropriate standards;

- a reliable supply of wheelchairs and spare parts; and

- wheelchair services that assist the user in selecting and being fitted with a wheelchair, provide training in its use and maintenance, and ensure follow-up and repair services.

Personnel involved in each area of wheelchair provision need to have the correct skills and knowledge. This means that training is essential for those involved in wheelchair provision.

Design, production and supply

The design of a wheelchair depends on a number of factors:

- the physical needs of users;

- the way and the environment in which the wheelchair will be used; and

- the materials and technology available where the wheelchair is made and used.

Wheelchairs can be produced in the country or outside the country. Those produced outside the country are often mass produced and imported as new or used wheelchairs. Wheelchairs can be supplied to wheelchair service providers by manufacturers, agents or distributors, or by organizations specializing in wheelchair supply.

Information on design, production and supply is provided in Chapter 2.

Service delivery

Appropriate provision of wheelchairs is most important in the successful rehabilitation of people who need a wheelchair for mobility. Historically, however, wheelchair service delivery has not been an integral part of rehabilitation services. This is due to many factors, including poor awareness, scarce resources, a lack of appropriate products, and a lack of training for health and rehabilitation personnel in wheelchair service delivery.

In many countries, users depend on charity or external donations. Donated wheelchairs are often inappropriate and of poor quality, giving further problems for the user and for the country in the long run. Users are not in a position to demand good quality from charities. A study in India revealed that 60% of wheelchair users who had received donated wheelchairs stopped using them owing to discomfort and the unsuitability of the wheelchair design for the environment in which it was used (18).

The result is that many people who require a wheelchair do not receive one at all, while those who do often get one without any assessment, prescription, fitting and follow-up. Many users, even people with spinal cord injury, often get wheelchairs without a cushion or basic instructions, which can lead to pressure sores and even premature death.

There is, however, increasing awareness of the importance of providing individual assessment, fitting and training in how to use a wheelchair. In a number of less-resourced settings, wheelchair services have been established using different models of service delivery. Such models include centre-based or community-based services, outreach services, mobile “camp”-style services and donations of imported wheelchairs. In countries where user groups are well informed and service providers have the necessary knowledge and support, wheelchair services are becoming integrated into existing rehabilitation activities. The common aim is to ensure that users are given skilled assistance in selecting the most appropriate wheelchair for their needs.

Information on wheelchair services is provided in Chapter 3.

Training

In less-resourced settings, limited training opportunities result in few people being trained to manage the provision of wheelchairs and other assistive devices. Scarcity of trained personnel to assist in choosing and obtaining a wheelchair becomes a barrier to participation (19).

Existing courses for health and rehabilitation professionals provide little input on wheelchair service delivery and related issues. In some instances, national personnel may have had informal training from expatriate personnel, but such training is often limited to the products available in the country and the trainer's own experience and abilities. If the training is not recorded it is not replicable, and the resulting skill levels are not measurable. It is difficult for local personnel to continue practising skills derived from this type of informal training once the trainers and original users leave the service.

The lack of formal training has resulted in a lack of recognition of specialist skills in wheelchair provision. In an attempt to address these needs, some initiatives have been taken by development organizations.

Detailed information on training is provided in Chapter 4.

1.8. Types of wheelchair

No single model or size of wheelchair can meet the needs of all users, and the diversity among users creates a need for different types of wheelchair. Those selecting wheelchairs, in consultation with the user, need to understand the physical needs of the intended user and how he or she intends to use the wheelchair, as well as knowledge of the reasons for different wheelchair designs.

The physical needs of users

The ability to adjust or customize a wheelchair to meet the user's physical needs will vary, depending on the type of wheelchair. Often, wheelchairs are available in at least a small range of sizes and allow some basic adjustments.

Wheelchairs designed for temporary uses (for example, to be used in a hospital to move patients from one ward to another) are not designed to provide the user with a close fit, postural support or pressure relief. Orthopaedic or “hospital” wheelchairs are an example of this type (see Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

Wheelchair designed for temporary user.

For long-term users, a wheelchair must fit well and provide good postural support and pressure relief (Fig. 1.6). A range of seat widths and depths, and the possibility to adjust at least the footrest and backrest height are important in ensuring that the wheelchair can be fitted correctly. Other common adjustments and options include cushion types, postural supports and an adjustable wheel position.

Fig. 1.6

Wheelchair designed for long-term user.

Highly adjustable or individually modified wheelchairs are designed for long-term users with special postural needs (Fig. 1.7). Such wheelchairs often have additional components added to help support the user.

Fig. 1.7

Wheelchair designed for user with postural support needs.

How the wheelchair is used

Wheelchair designs vary to enable users to safely and effectively use their wheelchair in the environment in which they live and work.

A wheelchair that is used primarily in rough outdoor environments needs to be robust, more stable and easier to propel over rough ground. Fig. 1.8 illustrates an example of a three-wheeled wheelchair that would be well suited to outdoor use. In comparison, a wheelchair that is used indoors on smooth surfaces needs to be easy to manoeuvre in small indoor spaces.

Fig. 1.8

Wheelchair suitable for outdoor use.

Many users live and work in a range of settings, and a compromise is therefore often necessary. Fig. 1.9 shows a robust wheelchair with a relatively short wheelbase but large castor wheels. This wheelchair could be used both indoors and outdoors.

Fig. 1.9

Wheelchair suitable for indoor and outdoor use.

Users need to be able to get in and out of the wheelchair easily, to propel it efficiently and to repair it. Users may need to transport their wheelchair, for example in a bus or car (Fig. 1.10). Different wheelchair designs allow for wheelchairs to be made more compact in different ways. Some are cross-folding (Fig. 1.10), while others have quick-release wheels (Fig.1.11. and Fig.1.12.) and the backrest folds forwards.

Fig. 1.10

Folding wheelchair.

Fig. 1.11

Quick-release wheels.

Fig. 1.12

Detachable wheels.

These needs and their related wheelchair design features are discussed in Chapter 2.

Materials and technology available

Wheelchair designs vary, depending on the materials and technology available for production and repair, For example, wheelchair designers must take into account the strength and variability of the available materials to avoid premature failure. In the case of failure, the wheelchair should be easily repairable (20). See Chapter 2 for more information on this topic.

1.9. Stakeholders and their roles

1.9.1. Policy planners and implementers

Policy planners and implementers are directly involved in the planning, initiation and ongoing financial, advisory and legislative support of wheelchair provision. The role of policy planners includes the following.

- Wheelchair provision policy is developed in consultation with other stakeholders, aiming at effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for people with disabilities. This includes:

- facilitating the personal mobility in the manner and at the time of their choice and at an affordable cost;

- access to wheelchairs, including making them available at an affordable cost;

- providing training in mobility skills to people with disabilities and to rehabilitation personnel; and

- encouraging entities that produce wheelchairs and other mobility aids within the country

- Standards for wheelchair products, service delivery and training are adopted, promoted and enforced.

- Measures are taken to ensure that wheelchair provision is equitable and accessible to all, including women and children, the poorest and those in remote areas.

- Wheelchair services are developed as an integral part of health care structures and in coordination with associated services, such as rehabilitation, prosthetic, orthotic and community-based rehabilitation services.

- Sustainable funding policies for wheelchair provision are developed.

- Wheelchair user groups and disabled peoples' organizations are involved at every stage from planning to implementation.

According to United Nations Standard Rules and the Convention, it is the primarily responsibility of countries to make wheelchairs available at an affordable cost. Ensuring the availability of wheelchair services within a country does not necessarily mean the direct provision of services by the government. Nevertheless, the government can work closely with nongovernmental and international nongovernmental organizations, development agencies, user groups and the private sector to develop national policies and a provision system. Furthermore, in developing the policy one needs to ensure that wheelchair services are cohesive and closely linked with national health and rehabilitation strategies.

Box 1.2Wheelchair provision and government ministries

Which ministry is typically responsible for wheelchair provision?

Wheelchair provision impacts on a number of government ministries and authorities. Ministries of health are generally responsible for health care and rehabilitation services, and therefore have a primary responsibility for wheelchair provision. In some countries, however, other ministries take a leading role. In India, wheelchair services are provided by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and in Ghana by the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare. In Kenya, a consortium of the Ministry of Health, social welfare services and nongovernmental organizations facilitates wheelchair service delivery within the country. Other ministries can also play a role, as the needs of users include economic and social issues that may be addressed by the ministry of social welfare or similar.

Ministries responsible for employment and education have a role in ensuring the rights of wheelchair users. Thus, unless the responsible ministries or authorities ensure that wheelchair users have access to buildings and public transport, they will not be able to participate in educational, economic and social activities.

1.9.2. Manufacturers and suppliers

An organization may be involved in one or more of the areas of manufacturing and supplying wheelchairs. Supplying means delivering wheelchairs to service providers, either through sale or donation. The role of manufacturers and suppliers of wheelchairs is to develop, produce or supply wheelchairs that meet the needs of users in different contexts. This includes:

- manufacturing or supplying products that are appropriate for the use to which they will be put;

- ensuring their products meet or exceed relevant wheelchair standards;

- providing wheelchairs through wheelchair services that offer, as a minimum, assessment, fitting, user training and follow-up; and

- ensuring that wheelchairs can be repaired locally.

Irrespective of the service model used to provide wheelchairs, it is recommended that suppliers exercise their responsibility by ensuring that:

- the service provider has the capacity to provide the supplied wheelchairs in a reasonable and responsible manner; and

- the supply is based on an assessment of the situation in the country or region and considers the impact on local manufacturers and service providers.

1.9.3. Wheelchair services

Wheelchair services provide the essential link between the users and the manufacturers and suppliers of wheelchairs. Service providers include:

- government wheelchair services

- nongovernmental organizations that provide such services

- the private sector

- hospitals and public health centres.

The main role of a wheelchair service is to assist users to choose the most appropriate wheelchair, to ensure that it is adjusted or modified to suit their individual needs, to train users, and to provide follow-up and maintenance services. Service providers also play a role in:

- giving feedback to manufacturers and suppliers about wheelchair design;

- developing referral networks; and

- developing and finding sustainable funding sources for wheelchairs and services.

1.9.4. Professional groups

Rehabilitation is a question of teamwork. Professionals such as therapists, health/nursing personnel, orthotists/prosthetists, physiatrists and others can play a major role in providing quality services, training personnel as well as users, enhancing the quality of life of the users, and sharing and documenting best practices. A team comprising all groups of rehabilitation personnel can ultimately benefit the user and has in particular proven useful in the development of the new profession or discipline of wheelchair provision. More professional groups need to be involved in wheelchair provision in less-resourced settings. A good example of such involvement is the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO), which has supported the development of structured professional training for wheelchair technologists.

The role of professional groups includes:

- guiding and supporting the activities of those responsible for wheelchair services;

- advancing the practice and standards of wheelchair service delivery;

- facilitating the placement and secondment of wheelchair professionals;

- facilitating the exchange of information; and

- promoting the education and training of wheelchair professionals.

Box 1.3Wheelchair industry association in Africa

In Africa, the Pan Africa Wheelchair Builders Association represents those involved in wheelchair design, production, funding and distribution. The Association was formed following a meeting of African wheelchair producers in Zambia in 2003 and is now established in Moshi, United Republic of Tanzania. One of its main activities is networking among wheelchair builders to support each other and to share resources.

1.9.5. International nongovernmental organizations

International nongovernmental organizations are often involved in facilitating wheelchair provision where there is little or no national service delivery. The policies and practices of these organizations should promote coordinated wheelchair provision that is equally accessible to all.

The role of international nongovernmental organizations in wheelchair provision includes:

- meeting the immediate needs of users where local wheelchair provision is lacking;

- supporting the state to fulfil its obligations concerning wheelchair provision;

- assisting the national authorities to develop a proper wheelchair service delivery system within the country;

- ensuring their activities are part of a broader long-term strategy acknowledged and supported by relevant authorities (e.g. the government);

- building the capacities of disabled people's organizations in accessing wheelchairs and developing partnerships;

- facilitating links between the various stakeholders – users, wheelchair service providers and governments;

- implementing wheelchair services by providing training expertise where none is available locally, and building capacities for both the technical and organizational aspects of wheelchair service delivery; and

- establishing services or pilot projects that include best practices for replication by governmental, nongovernmental and international nongovernmental organizations.

1.9.6. Disabled people's organizations

Disabled people's organizations have a crucial role to play in the planning, initiation and ongoing support of wheelchair service delivery. As organizations, they are able to advocate more effectively than individuals for users' needs.

To be effective, disabled people's organizations need knowledge and experience with appropriate products and services. Such organizations played an important role in preparing the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and will continue to be involved in its implementation in the future. Wheelchair users have an important role to play in implementing Article 20 of the Convention concerned with personal mobility and of Article 26 addressing habilitation and rehabilitation.

The role of disabled people's organizations in wheelchair provision includes:

- defining user's needs and barriers to equal participation;

- raising awareness of the need for effective wheelchair provision and financing;

- consulting with policy planners and implementers in the development of wheelchair services;

- raising awareness of wheelchair services, and identifying people who need wheelchairs and linking them with wheelchair services;

- monitoring and evaluating wheelchair services;

- advocating against inappropriate wheelchair provision, and that wheelchair services comply with agreed guidelines; and

- supporting users by providing peer support and training.

1.9.7. Users, families and caregivers

Users and their groups are at the centre of developing and implementing wheelchair provision (Fig.1.13). They can help ensure that wheelchair services meet their needs effectively.

Fig. 1.13

Users group.

The role of users includes:

- participating in the planning, implementation, management and evaluation of wheelchair provision;

- participating in the development and testing of wheelchair designs;

- working within wheelchair services in clinical, technical and training roles; and

- supporting and training new users.

Some users permanently rely on members of their family to assist with day-to-day activities of living, while others may be more independent. Where a family member or caregiver is responsible for assisting a user on a daily basis, such as a parent of a child with cerebral palsy, he or she should also be involved in all the roles listed above for users.

Family groups for parents, siblings and other relatives of children with disabilities are encouraged to undertake the activities listed under in Section 1.9.6.

Box 1.4Wheelchair user at policy and implementation level in Uganda

In Uganda, a wheelchair provision stakeholders' meeting was held in 2004, hosted by the Ministry of Health and sponsored by the Norwegian Association for the Disabled. This allowed users, disabled people's organizations, producers, government departments and donors to contribute their perspectives on the current situation of wheelchair provision, to agree on long-term goals, and to plan how to achieve them. The meeting led to the appointment of a wheelchair user as Wheelchair Project Officer within the Ministry of Health. This person's own experience has enriched the process of wheelchair service development in the country by bringing a user's perspective to the policy and implementation level.

Summary

- About 1% of a population need a wheelchair.

- Rights to wheelchairs are outlined in the United Nations policy instruments “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities” and “Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities”.

- Using an appropriate wheelchair benefits the health and quality of life of the user, and can lead to economic benefits for the user, the user's family and society as a whole.

- Wheelchair provision includes the design, production and supply of wheelchairs and wheelchair service delivery.

- When developing approaches to wheelchair provision, it is necessary to consider financial and physical barriers for users, their access to rehabilitation services, and user education, information and choice.

- There is a need for different types and sizes of wheelchair owing to the diversity of needs among users.

- Stakeholders involved in wheelchair provision include policy planners and implementers; manufacturers, suppliers and donors of wheelchairs; providers of wheelchair services and professional groups; national and international nongovernmental organizations and disabled people's organizations; and users, their families and caregivers.

References

- 1.

- Sheldon S, Jacobs NA, editors. Report of a Consensus Conference on Wheelchairs for Developing Countries; Bangalore, India. 6–11 November 2006; Copenhagen: International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics; 2007. [8 March 2008]. http://homepage

.mac.com /eaglesmoon/WheelchairCC /WheelchairReport_Jan08.pdf. - 2.

- Concept note. World Report on Disability and Rehabilitation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [8 March 2008]. http://www

.who.int/disabilities /publications /dar_world_report_concept_note.pdf. - 3.

- The Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities Preconditions for Equal Participation. New York: United Nations; 1993. [8 March 2008]. http://www

.un.org/esa /socdev/enable/dissre03.htm. - 4.

- Millennium Development Goals. New York: United Nations; 2000. [8 March 2008]. http://www

.un.org/millenniumgoals. - 5.

- Poverty reduction strategies. Washington DC: World Bank; 2007. [8 March 2008]. http://web

.worldbank .org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL /TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/EXTPRS /0,,menuPK:384207∼pagePK :149018∼piPK :149093∼theSitePK:384201,00.html. - 6.

- Krizack M. It's not about wheelchairs. San Francisco, CA: Whirlwind Wheelchair International; 2003. [8 March 2008]. 2003. http://www

.whirlwindwheelchair .org/articles /current/article_c02.htm. - 7.

- Rushman C, Shangali HG. Wheelchair service guide for low-income countries. Moshi, Tanzanian Training Centre for Orthopaedic Technology: Tumani University; 2005.

- 8.

- Rushman C, et al. Atlas of orthoses and assistive devices: appropriate technologies for assistive devices. 3rd ed. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006.

- 9.

- Howitt J. Patronage or partnership? Lessons learned from wheelchair provision in Nicaragua [thesis]. Washington, DC: Georgetown University; 2005.

- 10.

- Fitzgerald SG, et al. Comparison of fatigue life for 3 types of manual wheelchairs. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;82:1484–1488. [PubMed: 11588758]

- 11.

- Phillips B, Zhao H. Predictors of assistive technology abandonment. Assistive Technology. 1993;5:36–45. [PubMed: 10171664]

- 12.

- Beattie S, Wijayaratne L. A study of the cost of rehabilitation of spinal cord injured patients in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Motivation; 1999. [25 March 2008]. http://www

.motivation .org.uk/_history/History _SriLankaTotalRehab.htm. - 13.

- Disability and Rehabilitation Team (DAR). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [26 July 2006]. http://www

.who.int/disabilities /introduction/en/ - 14.

- Time for equality at work. Global Report under the Follow-up to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2003. [8 March 2008]. http://www

.ilo.org/dyn /declaris/DECLARATIONWEB .DOWNLOAD_BLOB/Var_DocumentID=1558. - 15.

- Helander E. Prejudice and dignity: an introduction to community based rehabilitation. 2nd ed. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 1999.

- 16.

- Global Survey on Government Action on the Implementation of the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006. [8 March 2008]. http://www

.un.org/disabilities/default .asp?navid =9&pid=183. - 17.

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; [6 March 2008]. http://www

.un.org/disabilities/default .asp?id=259. [PubMed: 29885750] - 18.

- Mukherjee G, Samanta A. Wheelchair charity: a useless benevolence in community-based rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2005;27:591–596. [PubMed: 16019868]

- 19.

- Scherer MJ, Glueckauf R. Assessing the benefits of assistive technologies for activities and participation. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2005;50:132–141.

- 20.

- McNeal A, Cooper RA, Pearlman J. Critical factors for wheelchair technology transfers to developing countries – materials and design constraints; Proceedings of the 28th Annual RESNA Conference [CD-ROM]; RESNA; Atlanta, GA. 2005. pp. 25–27.

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- INTRODUCTION - Guidelines on the Provision of Manual Wheelchairs in Less Resourc...INTRODUCTION - Guidelines on the Provision of Manual Wheelchairs in Less Resourced Settings

- polygalacturonase, partial [Phleum pratense]polygalacturonase, partial [Phleum pratense]gi|4826572|emb|CAB42886.1|Protein

- MIR3682 microRNA 3682 [Homo sapiens]MIR3682 microRNA 3682 [Homo sapiens]Gene ID:100500850Gene

- rhaA [Escherichia coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655]rhaA [Escherichia coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655]Gene ID:948400Gene

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...