All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: tni.ohw@snoissimrep).

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Operations Manual for Delivery of HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment at Primary Health Centres in High-Prevalence, Resource-Constrained Settings: Edition 1 for Fieldtesting and Country Adaptation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Operations Manual for Delivery of HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment at Primary Health Centres in High-Prevalence, Resource-Constrained Settings: Edition 1 for Fieldtesting and Country Adaptation.

Show detailsThe community is made up of members of the population served by your health centre. These may be HIV-positive people already enrolled in chronic HIV care at your centre. Or they may be people who are not living with HIV, but who are ready to support and improve the delivery of quality HIV care in their community. In areas with high HIV prevalence, most people, if not living with HIV, will have been affected by HIV

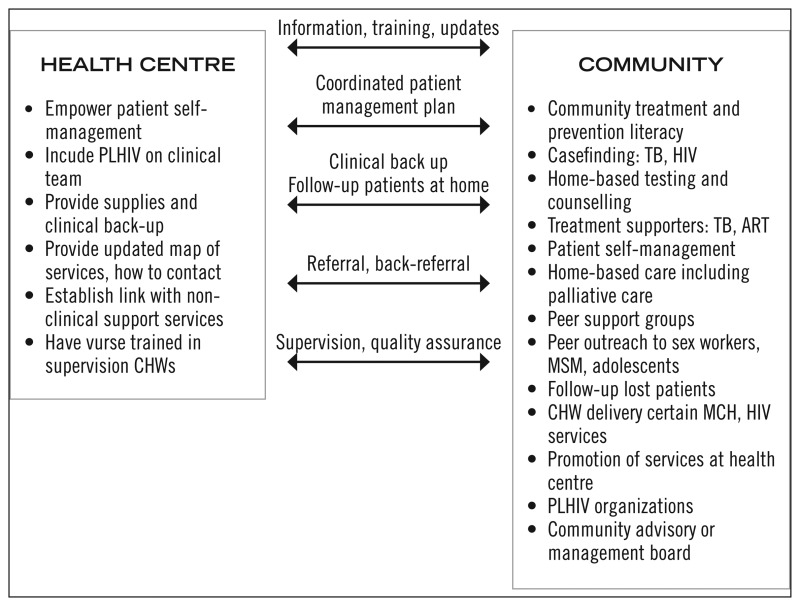

The community adds to the delivery of high quality HIV services in many ways. In addition it supports the health centre in the delivery of these services, resulting in improved quality of care. Community involvement comes in the form of both formal and informal activities. Formal structures may be established including, community or faith-based organizations (CBOs, FBOs); community health workers under the supervision of district health networks or non-governmental organizations (NGOs); DOTS supporters for the national TB system; peer outreach services to high risk groups, as well as home based and palliative care. The resources vastly underutilized by formal health systems include the ‘informal’ resources in the community in the form of PLHIV support groups; treatment supporters; as well as PLHIV, friends and families.

Health workers have technical skills that members of the community may not have, and these skills should be shared to ensure quality of community-based care. The community, in turn can form a significant component in the delivery of quality HIV services; including counselling, adherence support, development of a referral framework, and dissemination of information.

When planning for and delivering comprehensive HIV services at the health centre, that key community stakeholders are included at all times. Involving community stakeholders in Integrated HIV services at your health centre can also improve the quality of care received by your patients. Determining various ways to involve people living with HIV who are also on treatment is an important means of achieving effective and sustainable services. Therefore, planning for quality HIV care and treatment should specifically include who should be involved and how linkages between health facility and communities can be maximized and become an integral part of the continuum of care

4.1. COMMUNITY ROLE IN PREVENTION, CARE AND TREATMENT

It is important to approach HIV as a chronic disease and thereby focus on a patient-centred approach, as patients take on their role as the primary manager of their own chronic disease. It is also important to acknowledge the imbalance of power between patients, the community and health workers in order to build good relationships and help strengthen community structures in ways that support long-term patient self-management. HIV care may start at the health centre, but with increasing patient self-management, the vast majority of care takes place in the home and in the community.

Community participation can serve to:

- raise awareness, disseminate information and reduce stigma through education, acceptance and political buy-in;

- improve treatment and care outcomes by providing leadership and supportive services;

- assist in assessing, coordinating and mobilizing resources that complement health centre and hospital services;

- improve services as HIV care and treatment moves from an acute-care model to a chronic-care framework;

- support a sustainable patient-centred approach.

HIV is a life-long diagnosis and the long-term medical and psychosocial consequences of HIV can be mitigated by sustainable community-based services. For many reasons, the needs of PLHIV cannot be met by the health centre alone:

- health centres are often under-resourced;

- the type of support needed by PLHIV is not always health-related;

- PLHIV may respond better to non-medical people;

- distance from the health centre to the patients home may be great; whereas the patient lives within the community.

■. Health centre role in community linkages

The health centre can help to ensure the effective seamless community linkages needed for good chronic care of PLHIV. Key functions of the health centre include supporting community structures that offer adherence support, patient self-management and psychosocial support.

An important mechanism to facilitate the linkages between the community and the health centre is the establishment of a community advisory board (CAB). The CAB is composed of interested stakeholders from the community as well as members of the health centre team. The role of the CAB and steps to form it are discussed below. It is essential that health centres and CABs establish a plan that links community-and home- based care activities with health centres, and that incorporates all key stakeholders involved in patients' treatment needs. Formalized referral systems should be developed to link health centres and community-based resources to their patients.

■. Interaction between the health centre and community structures

It is important to formally link with community and home-based care structures that provide additional services to PLHIV and their families in the areas of physical, preventive, psychological/spiritual, and social care. These links were introduced in the Integration chapter.

Use participatory approaches to engage with the community and to find mutually acceptable solutions for services and linkages.

Participatory methods are tools to allow greater communication and discovery between the health centre and targeted community. This approach may take more time, but the investment ensures a better working relationship as well as, targeted, accepted and more sustainable solutions.

Exercises such as role-play, community mapping, spider diagrams, and wheel charts can break down barriers between health centre staff and community workers, encouraging both to adopt a common language for identifying and solving problems together.

The health centre should provide community groups with understandable, culturally appropriate and accurate treatment and prevention literacy materials and training.

■. Promoting health centre and community services

The health centre and CAB can work together to strengthen awareness and use of each other's services. PLHIV need to be aware of the services available and where and when it is most appropriate and effective to use them. This is especially true for PLHIV in rural areas where access to the health centre and district hospital mean considerable travel and expense. On the other hand, a well-timed visit to the health centre can prevent significant symptoms or disease progression. By working together, the team and the CAB can work out protocols for effective and efficient two-way referral.

■. How to map community assets

The point of a community asset mapping exercise is to generate a list of all organizations and facilities providing HIV-related services in your catchment area. It is important to initially focus on “assets” and not on “needs” within the community. The mapping exercise can reveal rich resources that can support a long-term, sustainable patient-centred approach to HIV in the community and relieve the health centres burden, thus improving chronic care. Use participatory tools to facilitate a common understanding of “community” and what roles stakeholders play.

4.2. COMMUNITY ADVISORY BOARD (CAB)

The goal of establishing a CAB is to define stakeholder opportunities, create a sense of shared responsibility, and ensure there is a platform for ongoing dialogue and cooperation. The CAB is independent of the health centre and can provide a forum for information, education and communication. The role of the CAB includes to:

- defining the vision of a comprehensive HIV care programme for the community within the bounds of national and provincial policy;

- assessing the available HIV services in the catchment area by undertaking a mapping exercise (see How to map community assets below);

- defining the roles and responsibilities of the care providers to achieve the vision at institutional and individual/staffing levels (i.e. developing standards);

- reviewing the programme established by the health centre, as well as community service provided by the health centre;

- assisting in development of a referral network;

- organizing community resources to advocate for services and funding;

- organizing community launch and acceptance of planned services when new to the community;

- monitoring service provision and review the impact on the community. This monitoring and review needs to include all key stakeholders involved in the treatment and care needs of the patient;

- advising the health centre whether the programme is meeting the needs of the community and also recommending that the health centre needs to meet specific community needs.

■. Forming a CAB

Establish an HIV CAB based on meetings between the district, health centre team and local stakeholders, such as community leaders (political or religious); PLWHA; women's groups, local associations, etc.

It is important to assure that:

- the CAB meets at regular intervals;

- board members regularly attend its meetings;

- board composition is reasonably representative of the diverse needs and interests of the communities the health centre serves;

- the role and functions of the CAB are clearly defined;

- board members understand their obligation to keep confidential any information about specific individuals and their HIV status.

■. Membership

This is a volunteer appointment. Members will have a chance to learn about HIV and influence what happens in their community, voluntary CAB role may be recognized by the community. It is strongly recommended that the CAB includes PLHIV.

Possible members of the CAB include:

- the health centre HIV coordinator;

- community stakeholders providing services (e.g. women's groups, faith leaders, etc.);

- people at risk1;

- local leaders (e.g. mayor's, chiefs, religious leaders, school principals etc);

- staff from other CBOs/FBOs/NGOs providing care at community and home levels;

- community health workers;

- health centre staff.

■. Functions of the CAB

Specific functions of the CAB are to:

- create linkages/referrals to known providers;

- create relationships with untapped entities;

- update contact list for stakeholders, assets, referrals, etc (see How to map community assets below);

- schedule and facilitate regular meetings;

- follow-up on tasks (monitor implementation);

- develop a plan to evaluate the impact of health centre-community integration and linkages (pre- and post- assessment tools, indicators, etc.) See Annex;

- evaluate impact.

Based on your context, there may be additional issues that need discussion and integration into CAB responsibilities. Before finalizing the system, the health centre/community team should also conduct several community meetings and present the results of its findings through this process for additional feedback and discussion.

Topics for consideration at CAB meetings:

- list and prioritize factors affecting community health (including HIV-related priorities);

- determine priorities for community and health centre interactions with the community;

- holding individual or focus group discussions with community leaders and/or stakeholders to discuss potential areas for interaction;

- develop implementation plan and discuss how to achieve priority items.

The following is an example from ICAP's experience with developing site CABs:

| CAB preconditions | CAB functions |

|---|---|

| Diverse/representative membership; members of HIV-affected community | Observe and report information about the community, as well as share information about HIV services with the community |

| Commitment and interest in learning; willingness to share | Serve as representatives of the community; share concerns and perspectives with HIV service providers |

| Ongoing and sufficient support | Build trust and acceptance of HIV services |

| Clear mechanism for information exchange | Promote access to HIV care |

| Meeting accessibility, e.g. location, transportation, child care | Advise on appropriate/culturally sensitive HIV information and activities |

| Sense of civic responsibility/volunteerism | Monitor ethical issues and patient rights |

| Recognition by community represented and institutions that are advised | Advocate for HIV services and funding |

■. Summary of community's role and linkages between the health centre and community

Community support can be even more extensive. In Tamil Nadu, India, substantial management and support responsibilities for health centres have been turned over to the community actively participates in health centre management and provides key supplies such as colour-coded waste bins (see Infrastructure chapter).

4.3. TECHNICAL ROLE OF THE COMMUNITY IN SERVICES

■. Community treatment and prevention literacy

Members of the different communities, especially PLHIV and at risk subgroups, are in the best position to make decisions about the approaches to treatment, prevention, and testing support that will be most effective in their communities. Treatment and prevention literacy is a community-based activity that helps people learn factual evidence-based information in a non-threatening manner, thus addressing stigma and discrimination, as well as myths about these issues in the community. It is important to engage the community to dispel myths and support changes in how cultures approach prevention so that your health centre can provide effective services.

This can be particularly important if:

- stigma and discrimination are particularly high in a community as it can be difficult to attract patients to treatment centres or to identify treatment supporters;

- myths around prevention in communities result in less regular use of condoms, or failed attempts to support the idea that people should have fewer sexual partners;

- myths about treatment adversely affect adherence (e.g. myths that assert treatment is poison, or claims that foodstuffs or local tribal remedies can cure HIV).

Key steps include the following:

- Involve people who are respected by the community;

- Make sure that treatment and prevention messages are clear, easily understood and delivered in the most culturally- and linguistically-appropriate manner – people in communities may speak more than one language even if they may not be able to read;

- Do not assume that people in communities who cannot read are not able to learn about the science behind treatment and prevention; even those with very little education are able to learn very well;

- Particular groups within the community who are at high risk of HIV infection will require more specific messages (men who have sex with men (MSM) or commercial sex workers (CSWs);

- Enlist the support of PLHIV and counsellors who will appeal to the particular sub-group.

Many examples exist of community-based treatment and prevention literacy.

The Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) of South Africa is a good example. TAC is active in most provinces of the country. It has created a movement of PLHIV and HIV-affected people who advocate for treatment access by ensuring that advocates are well informed about treatment and prevention science. Training takes place in local languages interspersed with scientific terms in English that the advocates learn with ease. The result is a critical mass of people who are informed and can support people on ART.

■. Peer support groups

Peer support groups assist with treatment support and literacy. They help patients deal with side effects, etc. and feelings of isolation and they work to combat stigma and discrimination. Peer support groups can be health centre-based or community-based. It is important that these groups are supported by the health centre and that effective linkages are established and maintained. Local peer support groups should be linked with national groups in order to facilitate advocacy and skill building. These grups are also important from a regional and international perspective to ensure that the diverse ‘voices’ of PLHIV are represented in decision-making at all levels.

The purpose of peer support groups is to:

- exchange information and skills;

- discuss positive and negative experiences and provide support for each other;

- provide extra support to PLHIV with managing symptoms, side effects and challenges of lifelong treatment adherence;

- improve the sense of self-esteem of PLHIV and help them become self supporting (both of which are necessary in achieving good long-term chronic care and patient self-mangement).

Consider separate peer support groups for peer outreach to vulnerable groups as it is important to consider the needs of specific groups, and when necessary, to establish separate peer support groups for them. These may be for women, men, children or other vulnerable people such as MSMs, CSWs and alcohol or substance-users. Different target groups may require different approaches since they may have varying needs, some of which may be specific to that group. It is helpful to ensure that people are comfortable and prepared to take advantage of the benefits offered by the peer process.

■. PLHIV organizations

PLHIV organizations and networks often begin by forming support groups based within the health centre or in the community. Their role in providing advocacy, technical support through treatment and prevention literacy, as well as psychosocial support are important and should be bolstered by the health centre and the CAB. Support groups may also become independent from existing health centre or community structures over time, although they will still benefit from continued support and linkages.

■. Treatment supporters (TB, ART)

Treatment supporters are key in providing PLHIV with the assistance they need to adhere to treatment regimens, and to increasingly progress to self-management of their HIV, especially when starting life-long treatment. Treatment supporters may be linked to health centres, community-based or family-based.

In many cases, treatment supporters are experienced PLHIV who have learned to manage their own treatment and prevention strategies, and to deal well with the psychosocial impact of HIV disease. Their role is to pass this expertise on to their clients.

Treatment support should be executed in a manner that:

- is acceptable to PLHIV and their families;

- ensures that confidentiality is maintained, and treatment supporters do not inadvertently signal the HIV status of their clients through their duties. In many communities, disclosure of HIV status can lead to stigma and discrimination.

■. Assist with patient tracking (i.e. follow-up patient visit ‘no-shows’)

Community-based systems for supporting patients assist health centres with tracking patients lost to follow-up. Involving the community in developing mechanisms for follow-up is helpful in reducing the number of patients who are lost over time. Innovative follow-up mechanisms include home visits, including PLHIV on the clinical team, and mobile phone reminders (see Chapter 6, Monitoring services). It is important to ensure that patients consent to this tracking and that confidentiality is maintained.

Strategies for reaching out to patients and ensuring that they have adequate care that are developed in a particular community need to respond to the particular needs of patients who live there. Take into account that some patient groups may be more at risk than others. Some patient groups should be selected for extra attention and they often benefit from targeted interventions.

Pay special attention to groups of people at high risk of being lost to follow up:

- orphaned children

- MSM

- commercial sex workers

- migrant workers

- alcohol or other substance users.

Many individuals at high risk of not arriving for scheduled visits may be marginalized and difficult to reach. In many instances, they may respond favourably to targeted interventions delivered by people in support groups whose members come from these same risk categories. (see Peer support group section on p.49).

■. Psychosocial support

PLHIV whose symptoms are under control from a medical point of view may still face significant challenges due to HIV-related stigma and discrimination. Often, the challenges to treatment adherence; preventing and treating side-effects; and maintaining good follow-up with medical centres are not related to the patients medical condition at all. Psychosocial support is critical to ensuring positive outcomes for PLHIV who face these challenges in different ways. Therefore, effective community structures with both group and individualized approaches to psychosocial support need to be linked seamlessly to health centre- and community-based medical care services.

■. Home-based care, including palliative care

Community- and home-based care deliver services that respond to the continuing care needs of a PLHIV outside the health centre.

Community- and home-based care programmes:

- function as entry points for HIV testing and counselling, as well as identifying eligible candidates for ART;

- follow-up patients who are discharged from a health centre or hospital but who still require direct monitoring and need active care;

- provide continuing care so that families and communities handle some patient care needs;

- strengthen the chronic-care approach to HIV treatment, care and prevention by supporting structures close to home where decisions are made about adherence, prevention and side-effect management.

In addition, these programmes help to offset the financial and human capacity constraints of many health centres. These centres benefit from the additional resources offered, as well as providing support for quality community- and home-based care programmes.

There are several models of how community- and home-based care programmes can be structured and linked with health centres.

4.4. CASE FINDING (TB, HIV)

Once appropriate community-based structures are in place to support scale-up of testing for HIV and TB, the health centre should actively begin provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) and TB screening. PITC should be offered to all patients at the health centre (refer to PITC guidelines). Everyone who tests positive for HIV should be screened for TB. Likewise, all patients with TB symptoms should be offered HIV testing and counselling.

To reach people who do not come to health centres, community organizations should be contacted to determine appropriate community-based testing mechanisms that can be initiated or strengthened. This can include reinforcing client-initiated counselling and testing services; initiating testing services in CBOs or FBOs; and introducing home-based HIV testing and counselling.

Note that case finding is not just about identifying who is infected with HIV. Case finding should emphasize the positive benefits of HIV testing and counselling, including access to treatment, care and support services, as well as receiving feedback on behaviours that promote HIV prevention. Health centres should also emphasize that testing is not a one-off event. It is an ongoing process that needs to be linked to supporting individuals and communities in their prevention efforts, including assisting people who are already living with HIV.

Furthermore, testing should be seen as an opportunity to reinforce prevention strategies with people who test positive or negative. Case finding depends on testing.

■. Home based HIV testing and counselling

In some communities, home-based testing and counselling can be an effective way to increase the number of people who know their HIV status. Effective programmes will incorporate CBO and/or FBO services so that both people with HIV-positive or HIV-negative results receive support and are linked with health centre services for ongoing care.

■. Integrate MCH and HIV services

Community-based organizations can also help provide maternal and child-health (MCH) services. Links between MCH and HIV services can be a way to provide services more effectively, including nutrition counselling, etc. MCH services should be designed to include men as well as women in order to educate people as widely as possible.

4.5. COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKERS (CHWS)

Community Health Workers (CHWs) are valuable members of the clinical team that provides services to the community. CHW's may or may not be part of the district health network, but effective linkages are essential. CHWs are not a substitute for a weak health system and need to work in a strong health system with effective linkages to health centres. CHWs should receive adequate and sustainable remuneration for their work. Health centres and CABs need to identify the possible tasks that CHWs can realistically deliver (see the table on p.53 and note that each CHW can only effectively provide a limited number of services. Other services can be delivered by community/family volunteers/community carers). In some countries, TBAs deliver 40% to 50% of all infants and with special training they can play an important auxiliary role in HIV prevention and home-based testing.

Successful CHW programmes include:

- good planning and realistic expectations;

- identified person(s) in the health centre who liaise with CHWs;

- association with wider community mobilization efforts;

- appropriate selection and recruitment processes and then appropriate training;

- continuing education including educational and mentoring activities with health service staff to ensure understanding of the CHW role, as well as continuous health centre supervision and support;

- financial compensation for CHWs (there is no evidence that volunteerism can be sustained for long periods);

- adequate logistical support;

- political leadership and sustained commitment and investment;

- close working relationship between CHWs (and TBAs) and health center staff.

Assistance provided by CHWs

| Nutrition |

|

| Child health |

|

| PMTCT/maternal care |

|

| HIV care/ART and TB (including prevention by people who are HIV-positive to protect their own health) |

|

| Prevent HIV transmission |

|

| Malaria |

|

| Palliative care |

|

| Psychological/spiritual care |

|

| Social Care |

|

How to support community health worker activities

Organize a monthly meeting for community health workers who are involved in activities such as providing nutrition, a malaria, TB or HIV assistance. This is an important opportunity for health- centre staff to provide clinical support to community health workers. Having PLHIV on the clinical team and on the CAB bolsters the support provided in key areas.

Organize these meetings in collaboration with the CAB to ensure good links between health centre staff and the community health workers.

Hold separate meetings for community health workers in each area of work. For example, all community health workers involved in educating the community and identifying malnourished children should come to the same meeting.

Invite community health workers from NGOs in the district, as well as those who use the health centre as a base. In order to ensure that activities are sustainable, health centre workers should facilitate these meetings with a view to empowering and enabling NGOs to take the lead. Investing in NGO leadership will pay off in the long run; resulting in systems and programmes that support the efforts of PLHIV and maintain functional links with the health centre.

Ensure that several health centre staff are available to discuss problems with CHWs and to provide them with feedback.

Example: Agenda of a monthly meeting for community health workers

- Short educational session or demonstration of skills: this can be as simple as discussing the best way to explain HIV, or how to provide treatment support. The topic may be chosen by the nurse or the CAB depending on the needs of the specific group of community health workers. It is important to highlight the experiences of both the health centre and the community health workers, and learning should be in both directions.

- Report on educational and mobilization activities.

- Report on clinical activities and distribution of drugs and commodities (for community health workers with clinical activities related to malaria, TB or HIV, etc.).

- Follow-up of patients lost to treatment; treatment support, discussions of adherence problems, etc.

- Renumeration/payment for CHW work.

Footnotes

- 1

It is important for the health centre and CAB to determine the best approach to include various key populations at higher risk of HIV infection. This can best be accomplished by including most at risk populations in the CAB, some of whom are already infected with HIV. In this way, approaches to the target groups will be more acceptable, sustainable and effective. Sometimes, it will be difficult for people within these groups to participate because of the ‘double stigma’ they face or, more importantly, criminalization of their activities. The health centre and CAB must avoid putting these populations most at risk of arrest, or of getting in trouble with the law. In some countries, the outreach activities identify them as members of outlawed groups.

- COMMUNITY - Operations Manual for Delivery of HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment...COMMUNITY - Operations Manual for Delivery of HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment at Primary Health Centres in High-Prevalence, Resource-Constrained Settings

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...