This is an open-access report distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Public Domain License. You can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Treating Substance Use Disorder in Older Adults: Updated 2020 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2020. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 26.)

Treating Substance Use Disorder in Older Adults: Updated 2020 [Internet].

Show detailsKEY MESSAGES

- •

Strong social networks support older adults in achieving and maintaining recovery from substance misuse. Providers can help older adults develop and maintain a social network that promotes recovery and wellness.

- •

Older adults have to increase their health literacy to maintain recovery and prevent relapse.

- •

Providers need to engage older adults in illness management and relapse prevention activities specific to substance misuse with a focus on health and wellness.

- •

Providers can help older adults feel more empowered by understanding the normal developmental challenges of aging and age-specific strategies for promoting resilience and setting goals.

Chapter 7 of this Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) will most benefit healthcare, behavioral health service, and social service providers who work with older adults (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, mental health counselors, alcohol and drug counselors, and peer recovery support specialists). It explains how older adults who misuse substances can benefit from wellness strategies that support relapse prevention, ongoing recovery, and better overall health. The keys to wellness for this group are having strong social networks and participating in health and wellness activities that support recovery.

The high prevalence of isolation in older adults who misuse substances can negatively affect cognitive functioning and reduce well-being. Older adults who lack family ties or social networks may find maintaining recovery from substance misuse difficult. Healthcare, behavioral health service, and social service providers can help older adults who misuse substances reduce isolation and improve recovery outcomes by promoting broader social networks.

Maintaining recovery from substance use can be harder for older adults who have trouble understanding and using health information. It may also be more difficult for those with limited self-management skills (e.g., difficulty engaging in regular exercise, healthy eating, or medication adherence). Medical conditions common in later life can also reduce functioning. Providers can engage older clients in skill-building and wellness activities that will support resilience and overall health while also reducing the likelihood of a return to substance misuse.

Organization of Chapter 7 of This TIP

Chapter 7 addresses promoting social support and other health and wellness strategies relevant to older adults in recovery from substance misuse.

The first section of Chapter 7 describes the importance of social support in promoting and maintaining health, wellness, and recovery among older adults who misuse substances.

Types of positive social support, the impact of social isolation on health and wellness, and strategies for promoting and maintaining social support are examined.

The second section addresses how to promote other wellness strategies for older adults. This section specifically focuses on assessing and promoting health and wellness for older adults in recovery. It addresses health and wellness activities relevant to older adults, strategies for promoting health and wellness, illness self-management and relapse prevention approaches, and strategies for promoting resilience and empowerment among older adults, including goal setting.

The final section identifies targeted resources to support your practice, some of which appear in full in the Chapter 7 Appendix; additional resources appear in Chapter 9 of this TIP. Exhibit 7.1 provides definitions for key terms that appear in Chapter 7.

Box

EXHIBIT 7.1 Key Terms.

Social Support: The Key to Health, Wellness, and Recovery

People with significant social support tend to have healthier lifestyles, engage in fewer behaviors that risk health (e.g., substance misuse), and be more active. Older adults in long-term recovery from substance misuse have better outcomes when their social supports promote abstinence.1137,1138

Three major components of positive support for older adults are:

- •

Family and friends. Family members often provide most of an older adult's basic social support. Strong friendships and neighborhood supports can also be important to older adults. Friends often provide emotional support, and neighbors can offer immediate help in an emergency.

- •

Mutual-help groups. Mutual-help groups such as AA and NA can support abstinence and foster new social connections, a sense of belonging, and healthy lifestyles.

- •

Religious or spiritual supports. Participation in religious or spiritual fellowships can decrease social isolation and is associated with health and wellness.1139

In the 2015 World Values Survey, more than 75 percent of adults in the United States over age 60 responded that they considered themselves to be religious and sometimes or often contemplated the meaning of life (an indicator of a spiritual focus).1140

Many religions discourage drug use and alcohol use or misuse.1141,1142 Involvement in religious and spiritual organizations can give older adults a sense of meaning, optimism, and self-esteem, lessening the impact of stressful life events like the death of a significant other.1143 A sense of meaning and optimism can help maintain recovery from substance misuse.

The quality and diversity of older adults' social networks matter more than size in promoting health, well-being, and recovery and in lowering risk of substance misuse.1144,1145 For example, tense relationships with family members can increase stress, which can negatively affect older adults' health and avoidance of relapse. In addition, too much support from children, although well-meaning, may increase older adults' dependence and reduce their sense of self-efficacy and well-being. Conversely, work colleagues, social contacts at senior centers, and behavioral health service and healthcare providers can be additional sources of emotional support. Mutual-help groups such as AA and NA can provide older adults with a stable source of friendships and enhance the diversity of their social networks.

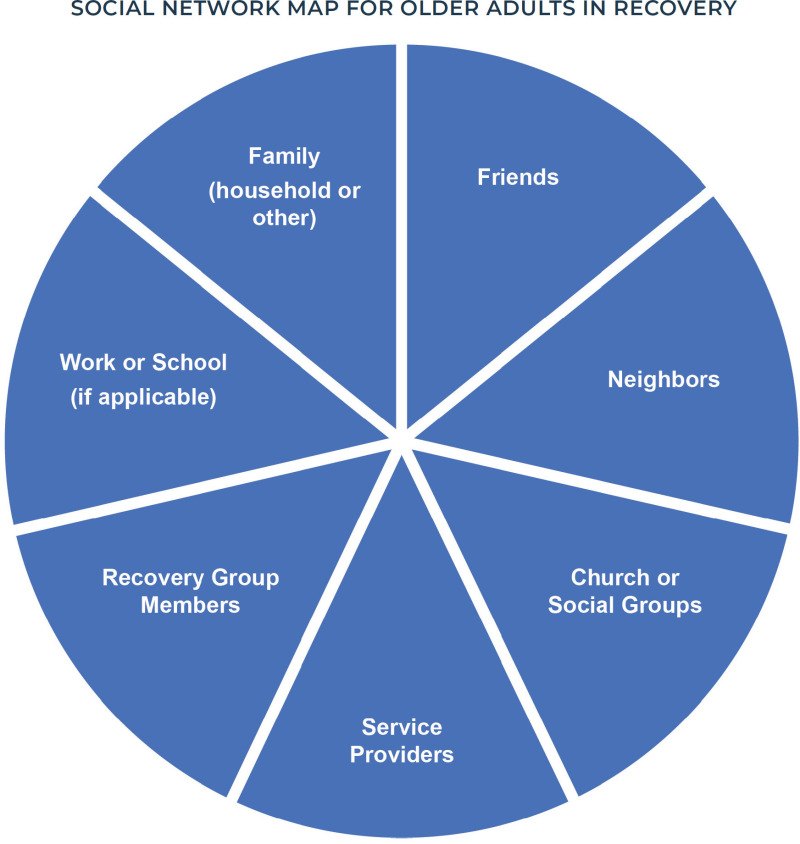

The consensus panel recommends that you assess the number of social connections older adults have and also gauge the quality and diversity of those connections and how they promote wellness and recovery. (See the Chapter 7 Appendix for the Social Network Map for assessing and discussing social networks with older adults.)

Social Isolation

Social isolation, linked to loneliness, is common in older adults. Their social networks narrow because of retirement, decreased physical functioning, and deaths of spouses, intimate partners, and friends.1146 A spouse or intimate partner is essential for many older adults' well-being. The death of a spouse puts older adults at high risk for social isolation, and may decrease life expectancy for men.1147 Loneliness is linked with substance misuse in some older women.1148

Box

ADDRESSING GRIEF.

Other factors that can add to social isolation for older adults include family members living far away, lack of transportation, cognitive decline, living alone or in unsafe neighborhoods,1151 poverty, physical disability,1152 and disruption of existing social networks via relocation to long-term care facilities.

Social isolation in older adults has been linked to:

- •

Increased likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors such as alcohol misuse and smoking.1153

- •

Increased risk of depression.1154

- •

Cognitive decline and risk for developing dementia.1155

- •

Poor overall health, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, sleep disturbances, and sedentary lifestyles.1156,1157

- •

Impairment in executive functioning, which makes it hard to engage in health-promoting physical activities1158 or follow a relapse prevention plan.

- •

Increased risk for falls, rehospitalization, and death from all causes, including suicide among men.1159

Box

SOCIAL ISOLATION AMONG OLDER ADULTS IN METHADONE MAINTENANCE TREATMENT.

The consensus panel recommends that you screen older adults for social isolation and help them learn about the link between social isolation and substance misuse as part of your efforts to educate clients on health literacy. (See the Chapter 7 Appendix for a discussion of the Lubben Social Network Scale, a social isolation screening tool for older adults.)

Promoting Social Support for Older Adults

A lifespan perspective suggests that social networks change over a person's lifetime. One of the unique aspects of older adults' social networks is that those networks naturally shrink as people age and their close family members and friends die. This shrinkage may also occur because older adults become increasingly aware of the limits of time left in life and choose to focus on the most rewarding relationships. Doing so may help them emphasize emotional support while deemphasizing less satisfying relationships.1161 A high degree of emotional closeness is associated with high levels of quality of life and well-being for older adults.1162

Strategies for improving social support for older adults in recovery from substance misuse should focus on expanding network size, increasing network diversity, and deepening the emotional closeness of network connections. Interventions to decrease social isolation and improve well-being should be adaptable to older adults' needs and interests, include their input about what works for them, and actively versus passively engage them (e.g., playing cards with friends versus watching TV together).1163

The consensus panel recommends the following interventions to promote social support for older adults who misuse substances.

Engage family members and other caregivers in recovery support. Perhaps the most important social support for older adults is frequent contact with family members (or other caregivers) who support their recovery. Help foster positive social contact between family members and older adults who misuse substances by:

- •

Involving family members and other caregivers in older adults' treatment (with express consent from clients).

- •

Educating clients, caregivers, and families about the importance of emotional and instrumental support for older adults' recovery. (An example of instrumental support is providing rides to appointments.)

- •

Educating caregivers about skillful ways to provide support.

- •

Educating family members about the importance of visiting the older adult when he or she is not misusing substances, rather than visiting only during substance-related crises (e.g., binge episodes).

- •

Recommending that family members and other caregivers participate in family support groups for caregivers and mutual-help groups for family members such as Al-Anon.

When family members are not nearby geographically or older adults are homebound, explore the possibility of clients' connecting with family members regularly via phone or video calling services. Studies show that frequent contact between older adults and family members via online communication applications decreases loneliness and increases social contact for the older adults.1164

See Chapter 4 of this TIP for more information about family and caregiver involvement.

Enlist neighborhood supports. Social cohesion in neighborhoods is another factor that promotes the health and well-being of older adults. For example, when neighbors provide instrumental support for older men and emotional support for older women, the older adults attain better physical health and mental well-being.1165 You can help older adults build up this support by:

- •

Asking which neighbors they are close to.

- •

Helping them identify which neighbors have provided which kinds of support to them in the past.

- •

Asking them which neighbors they think would be supportive of their recovery efforts.

Many communities have befriending programs that send “friendly visitors”—who are trained volunteers—to the homes of older adults who have no close ties to neighbors or nearby relatives, or who are homebound. Visitors spend an hour or two a week with older adults to provide companionship, friendship, and linkage to health and wellness resources. They can often identify signs of substance misuse in the older adults they visit and help link these older adults to treatment resources. Contact your local Area Agency on Aging (AAA; see Resource Alert) to find out whether it or another organization in your community has a friendly visitor program.

Box

RESOURCE ALERT: AREA AGENCIES ON AGING.

In rare cases, friends and family members may commit elder abuse.1166 If you think such mistreatment is occurring, screen your older client for elder abuse (see Chapter 3 of this TIP).

Link clients to social and behavioral health support groups. In addition to linking your older clients to mutual-help groups such as AA, NA, or SMART Recovery, which can provide social as well as recovery support, refer them to social and behavioral health support groups in the community. These can range from smoking cessation groups to walking clubs to depression support groups. Create a list of organizations that offer support groups for older adults and actively link your client to one or more groups that are appropriate, accessible, and acceptable to him or her. (See Chapter 4 of this TIP for more information on active linkage to community resources and referral management.)

Agencies and organizations with support groups that may be helpful to older adults include:

- •

Recovery support organizations.

- •

Senior centers.

- •

Adult day health services.

- •

Community and private hospitals.

- •

Healthcare, behavioral health service, and social service programs for older adults.

- •

Veterans programs.

- •

Coalitions and advocacy groups for older adults.

- •

Assisted living facilities.

- •

Faith-based organizations.

- •

Community centers.

Link clients to peer recovery support specialists. An important strategy for increasing social support for older adults in recovery is to link them to peer recovery support services.1167,1168,1169 Peer recovery support specialists work in a variety of settings, including addiction treatment programs, faith-based institutions, and recovery community organizations (RCOs).1170 (For information on RCOs, see www.recoveryanswers.org/resource/recovery-community-centers.)

Peer recovery support specialists offer four types of social support: emotional, instrumental, informational, and affiliational (i.e., facilitating contact with others to strengthen social networks).1171

Linking older adults to peer recovery support specialists can:

- •

Increase and diversify older adults' social networks.

- •

Introduce older adults to the culture of recovery.

- •

Facilitate engagement and active participation in community-based mutual-help groups.

- •

Prevent relapse by helping older adults stay connected to mutual-help groups.

Peer recovery support specialists who work with older adults should have age-specific training and a commitment to working with this age group. These specialists are often older adults who can share their own experiences with recovery at this stage of life.

See Chapter 2 of this TIP for more information on key strategies for providing support to older adults.

Educate clients about social media and online social networking support. Online technologies— including social media applications and social networking websites—may be an important way for older adults to expand their support networks. Videoconferencing and use of social networking, educational and informational websites, and online discussion forums can reduce social isolation and improve social support, self-efficacy, and empowerment among older adults.1172 In addition, information exchange about specific issues—such as substance misuse, recovery resources, chronic illness management, and health and wellness resources—in online social networks and discussion forums can boost well-being for older adults.1173 Many addiction-focused mutual-help groups offer online meetings through chat rooms, web-based forums, and telephone or videoconferencing applications.

Many baby boomers already use smartphones and online technologies. About 42 percent of adults ages 65 and older own smartphones, up from 18 percent in 2013; 67 percent use the Internet.1174 However, barriers to social media and mobile technology use include:1175,1176,1177

- •

The cost of owning a computer, tablet, or cell phone and data or Internet access fees.

- •

Lack of broadband infrastructure in rural and tribal areas.

- •

Concerns about privacy and what happens to personal information once it is posted on the web.

- •

Decline in cognitive and physical functioning, which hinders use. For instance, older adults may have physical or cognitive barriers in reading webpages that do not have universal accessibility, or difficulties using features of the device, like buttons on a cell phone or touchscreens.

Help older clients who are curious about or interested in trying online technologies for social support:

- •

Access basic information about using online technologies safely (e.g., protecting personal information, avoiding scams; for more information, see the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's [SAMHSA] TIP 60, Using Technology-Based Therapeutic Tools in Behavioral Health Services).

- •

Problem-solve ways to overcome access barriers (Chapter 4 offers problem-solving strategies).

- •

Learn about local and online resources that are appropriate and acceptable to them. For example, senior centers, libraries, community colleges, community centers, AARP, Senior

.net learning centers, and adult learning programs are potential sources of free or low-cost educational programs to help older adults learn how to use a computer and social media websites and applications. - •

Ask for support from family members or tech-savvy friends who can help set up a computer, tablet, or cell phone; teach them how to safely use social media and other apps; and provide ongoing support in their use of technologies.

Specific websites offering assistance with social media are listed in the folllowing Resource Alert.

Box

RESOURCE ALERT: CONNECTING OLDER ADULTS WITH SOCIAL MEDIA SUPPORTS.

Some older adults living in retirement communities or long-term care facilities have a built-in social network that facilitates drinking.1178 Older adults in such settings may perceive drinking as a pleasurable or necessary aspect of socializing with their fellow residents. If you have older clients who misuse alcohol to fit in to their residential setting, help them learn to feel comfortable saying “no” to too much—or any—alcohol in social situations. If you have older clients who enjoy the social aspects of drinking in these settings but engage in alcohol misuse, educate them about the importance of reducing their alcohol intake.1179

Promoting Wellness Strategies for Older Adults

This section reviews the eight dimensions of wellness and how to explore wellness from a client-centered perspective. It then examines strategies for promoting wellness, illness self-management and relapse prevention approaches, and strategies for promoting resilience and empowerment relevant to older adults in recovery from substance misuse.

What Is Wellness for Older Adults in Recovery?

Wellness is not simply abstinence from alcohol or drugs or the absence of illness or stress; it is being in good physical, emotional, and mental health.1180 To better promote wellness and recovery in older adults, effective strategies should include a focus on illness self-management and relapse prevention and an emphasis on health potential.1181

SAMHSA has identified eight dimensions of wellness1182 (Exhibit 7.2) that further a person's health, well-being, and recovery from substance misuse and mental disorders:

Box

EXHIBIT 7.2 SAMHSA Wellness Wheel.

- •

Emotional—Coping effectively with life and creating satisfying relationships

- •

Environmental—Occupying pleasant, stimulating environments that support well-being

- •

Financial—Being satisfied with current and future financial situations

- •

Intellectual—Recognizing creative abilities and finding ways to expand knowledge and skills

- •

Occupational—Personal satisfaction and enrichment from one's work

- •

Physical—Recognizing the need for physical activity, healthy foods, and sleep

- •

Social—Developing a sense of connection, belonging, and a well-developed support system

- •

Spiritual—Expanding a sense of purpose and meaning in life

The consensus panel recommends that you explore all of these dimensions of wellness as a way to help older adults sustain their recovery from substance misuse.

Talk with clients about their own wellness goals in each of the eight dimensions. (See “Collaborative Goal Setting” in this chapter for more information.) This will help you understand what wellness means to each client and open the conversation about ways to develop health and wellness in recovery. (See the Chapter 7 Appendix for the Health Enhancement Lifestyle tool to assess older adults' health and wellness.)

For older adults in retirement, occupational wellness may be more about satisfaction and enrichment from nonpaid work such as volunteering in the community or a satisfying hobby like gardening or painting.

Promoting Health and Wellness in Recovery

You can promote health and wellness among older adults in recovery from substance misuse by exploring obstacles to recovery, understanding their perspectives on health and wellness, and supporting their interest in and readiness to engage in activities that maximize health and wellness. The consensus panel recommends the strategies discussed below, which apply to diverse clinical and service settings, for promoting wellness among older adults in recovery.

General Wellness Promotion Strategies

Reduce fear, shame, guilt, and defensiveness related to substance misuse. Older adults may feel shame and guilt about acknowledging that they misuse substances. The first step in helping them achieve better health and wellness is to address their misconceptions about substance misuse and any fears they may have about treatment and the recovery process. One helpful strategy is to discuss substance misuse in a nonjudgmental way as a health issue like any other chronic illness (e.g., diabetes). Also express understanding and compassion to help older adults manage their fears and uncertainties about recovery from substance misuse and ways to engage in wellness activities to improve their health and well-being.1184

Identify wellness activities. Use the table in Exhibit 7.3 with clients to identify wellness activities that they find accessible, acceptable, and appropriate. Introduce the table by describing the eight dimensions of wellness and give some examples of activities in each domain. Then brainstorm with clients to identify specific activities in each domain that fit their preferences and wellness goals. With express consent from clients, ask supportive family members for suggestions on activities.

Box

EXHIBIT 7.3. Identifying Wellness Activities.

Strategies To Increase Motivation

Increase motivation to change health risk behaviors and participate in wellness activities through motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a nonconfrontational, respectful approach that can effectively help older adults resolve ambivalence about change and increase motivation to change a target behavior.1185 MI strategies can help older adults reduce alcohol consumption and tobacco use, improve general health, increase physical activity and exercise, improve diet, reduce cardiovascular risk factors, lose weight, and prevent disease.1186,1187

MI strategies can help older adults change health risk behaviors like intentional or unintentional misuse of prescription medications, and resolve ambivalence about participating in wellness activities. Use the following MI strategies to help older clients identify and plan for achieving target behaviors that reduce health risk, improve wellness, and sustain recovery from substance misuse:

- •

Identify a specific target behavior that the client is willing to explore (e.g., attending an educational session about the health risks of medication misuse for older adults or calling the local senior center to find out about a tai chi class). The more specific the target behavior, the more likely you and the older adult will be able to work together toward achieving the client's change goal.

- •

Apply MI communication skills (e.g., OARS— open questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summarization) to shape the conversation with clients to help them resolve ambivalence about change. (See the Chapter 7 Appendix for an example of using OARS.)

- •

Emphasize change talk through reflective listening.

- •

Help the client create a change plan for each target behavior by writing down the change goal and a timeframe for achieving that goal. (The “Collaborative Goal Setting” section has more information.)

- •

Follow up with the client to see whether the change plan is working or needs adjustment.

For more on MI, see SAMHSA's update of TIP 35, Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment (https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-35-Enhancing-Motivation-for-Change-in-Substance-Use-Disorder-Treatment/PEP19-02-01-003).

Educational Strategies To Address Nutrition, Exercise, and Fall Prevention

Provide education on nutrition, exercise, and fall prevention. Access to health information, a key component of health literacy, enables people to better manage their health and sustain recovery. Three key elements of preventive care for older adults in recovery from substance misuse are nutrition, exercise, and fall prevention. You don't need to be an expert in nutrition or fitness to provide older adults with accurate information about health. Just knowing a few things about these elements of wellness for older adults can help you get the conversation started.

Advise older clients to check with their healthcare provider before starting or dramatically changing their exercise routine or diet.

Begin by educating yourself. Explore the resources listed in the Resource Alert below for information on nutrition, exercise, and fall prevention for older adults. Then take a client-centered approach to client education and information exchange using these strategies:

- •

Ask older clients what they know about nutrition, exercise, and fall prevention for people their age.

- •

Provide small chunks of information that are personally relevant to older clients; use visual aids.

- •

Ask clients what they think of this information and how it affects their level of interest in or readiness to engage in health promotion activities.

- •

Develop an individualized change plan. If the information has an impact and clients are ready to act, brainstorm activities that they think are fun, easy, accessible, and personally relevant.

- •

Follow up at the next visit. Ask clients what worked and did not work, and help them adjust the change plan while making progress toward change goals.

Client education is a process of information exchange over time, not a single event. Information exchange can help you build a closer relationship with clients through a deeper understanding of their own experiences with making health behavior changes.

Box

RESOURCE ALERT: OLDER ADULT NUTRITION, EXERCISE, AND FALL PREVENTION.

Strategies for Complementary Therapies, Spirituality, and Ancillary Services

Encourage the informed use of complementary therapies and activities. Complementary and integrative medicine techniques can be categorized into three groups—natural products (e.g., vitamins, herbal products), mind-body practices (e.g., meditation, yoga), and other health approaches (e.g., homeopathy, naturopathy). (See “Resource Alert: Complementary and Integrative Health for Older Adults.”) Many complementary therapies and activities are appropriate for helping older adults maintain good health and well-being in ongoing recovery. For example, owning or interacting with a pet (e.g., in animal-assisted therapy) can increase physical activity, improve cardiovascular functioning, enhance socialization, lower blood pressure, and decrease loneliness in some older adults.1188 Tai chi, a low-impact exercise and meditative movement, may prevent falls by improving balance, strength, mobility, and flexibility.1189,1190 It may also help older adults sleep better.1191

Practicing mindfulness has many mental, emotional, spiritual, and health benefits that can enhance older adults' sense of well-being.

Mindfulness has been widely adapted and studied in the United States as a strategy for stress reduction and healthy coping. Mindfulness helps people develop open, nonjudgmental attention to present-moment experience. Older adults can use mindfulness skills to cope with stresses like physical pain and financial worries. Mindfulness may also increase older adults' social support, well-being, and ability to regulate emotional states like depression, anger, and anxiety.1192

You can incorporate mindfulness practices in work with older adults or refer your clients to local programs that teach mindfulness. For more on mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs, see the website of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at www.umassmed.edu/cfm.

Other complementary therapies and wellness activities appropriate for older adults in recovery include:

- •

Gentle or senior-friendly yoga.

- •

Dance and movement therapy.

- •

Low-impact fitness programs.

- •

Swimming and water therapy.

- •

Meditation.

The consensus panel recommends that you explore the benefits and potential downsides of complementary therapies with your older clients and work collaboratively with them to find the right ft based on cost, level of physical and cognitive functioning needed to participate successfully, age-specific adaptations, and ease of access.

Explore the spiritual dimension of wellness and recovery. As mentioned previously, participation in religious or spiritual fellowship can expand the social dimension of wellness for older adults. For example, one recent study found that more frequent attendance at church among adults ages 50 and older is associated with a sense of belonging and greater spiritual support, which are in turn associated with a greater likelihood of positive self-report of health.1193 Engagement in religious activities (e.g., praying, attending religious services) and spiritual practices (e.g., mindfulness, meditation), including the spiritual aspects of AA, are linked with better alcohol use outcomes, improved recovery from AUD, increased coping skills and ability to manage stress, decreased anxiety and depression, and improved cognition.1194,1195

To explore the spiritual dimensions of wellness and recovery with older clients, you can:

- •

Acknowledge that spirituality or religious engagement may be important to your clients' well-being.

- •

Be open to exploring clients' spiritual or religious beliefs and practices and their potential impact on clients' health, wellness, and recovery. Do not insert your own beliefs into the conversation.

- •

Explore how your clients' understanding of spirituality relates to their overall well-being, experience of recovery, sense of meaning and purpose, health, and coping with loss, stress, or adversity.

- •

Encourage active participation in personally relevant religious or spiritual activities such as attending religious services, attending AA or NA 12-Step meetings, praying, engaging in mindfulness or meditation, or “giving back” by becoming an AA or NA sponsor or volunteering in the community.

Actively link or refer older adults to ancillary services, such as:

- •

Health care provided by physicians with experience and training in geriatric medicine.

- •

Specialized pharmacy services.

- •

Health education programs.

- •

Disease prevention or wellness counseling services.

- •

Complementary therapies.

- •

Fitness programs for older adults.

Active linkage includes contacting the service or program you are referring your client to, getting a release from your client, giving written instructions to your client about how to access the service (e.g., name of provider, appointment time), and following up with the ancillary service provider via phone, letter, or email. (Chapter 4 of this TIP has more information about active linkage and referral management.)

Box

RESOURCE ALERT: COMPLEMENTARY AND INTEGRATIVE HEALTH FOR OLDER ADULTS.

Recognize and explore strengths. Older adults have a great deal of knowledge from their own experience, practical wisdom, and a wide range of skills and abilities. A strengths-based approach assumes that people do not simply survive difficult life circumstances, including substance misuse and the aging process itself, but can thrive in recovery and achieve enhanced health and wellness. Exploring older adults' strengths involves validating their interests, acknowledging and appreciating their successes, and inviting them to reflect on future possibilities.1196

Clinical Scenario: A Strengths-Based Intervention

Older adults in recovery from substance misuse who are widows or widowers may feel guilty about surviving and lose interest in life. The following scenario focuses on exploring an older adult's strengths to rekindle a sense of possibility about the future.

- •

AUD Recovery and Loss: An older adult in recovery from AUD drops out of AA after becoming a widower.

- •

Treatment Setting: Outpatient addiction treatment program

- •

Provider: Licensed alcohol and drug counselor

- •

Treatment Strategy: Strengths-based approach

Harry is 79 years old. He has been in recovery from AUD for 3 years. He initially attended AA meetings, became actively involved in the program, and attended recovery-oriented social gatherings with his wife, Ginny. When Ginny died suddenly, Harry stopped going to AA and isolated himself from family and friends. His daughter became worried about him and convinced him to go see a counselor.

At the initial interview, the provider acknowledges Harry for maintaining his abstinence through a very difficult time. This acknowledgement helps Harry feel more comfortable talking about how he has lost interest in going to meetings or spending time with family and friends. He says, “I just can't let myself have fun or feel joy anymore. It's like I would be betraying Ginny. I'm the alcoholic and she is the one who died too young. It should have been me.”

The provider offers Harry an affirmation and an open question that directs the conversation toward exploring Harry's strengths and an alternative story about his pulling back from life, “I appreciate your efforts to honor Ginny's memory. It seems like you really respect and appreciate how other people have touched you and contributed so much to your life. Not everyone has that quality. How did you come by that ability?”

Harry begins to tell a story about how he learned about respecting others early in his life and how important being respectful is to him. This opens the door for the counselor to explore Harry's other strengths and abilities. “What other abilities or talents would you say have contributed to your life?”

As the provider helps Harry identify his strengths, Harry starts to believe in himself again and gives himself permission to feel good. His story about honoring Ginny changes. He sees another way he can honor his wife: by getting back to living his own life. He decides to call his former AA sponsor about returning to his home group.

Promoting Self-Management and Relapse Prevention

Perhaps the most critical tasks for older adults who misuse substances are to achieve stability and maintain ongoing recovery. Sustaining recovery is challenging without a sense of health and well-being, especially for older adults with co-occurring mental disorders or multiple chronic illnesses. Relapse prevention planning is the key to helping older adults identify potential relapse triggers and build coping skills. Engaging older adults in chronic illness self-management programs, relapse prevention planning, continuing care, and ongoing recovery support can help them maintain long-term recovery.

Chronic Illness Self-Management

Chronic illnesses can increase isolation and interfere with substance misuse recovery efforts. Mental disorders like depression and anxiety are common in older adults. So are chronic health conditions: 80 percent of older adults have at least one chronic health condition, such as diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and chronic pain.1197 Illness self-management programs are an important part of integrated and client-centered care. They improve health outcomes, help people maintain higher levels of health functioning, and enrich quality of life by helping people develop skills to manage their symptoms and change attitudes and behaviors.1198

One such program, the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP),1199 is an evidence-based approach that has demonstrated effectiveness with older adults. CDSMP has helped people improve wellness across several dimensions, such as through improvements in exercise, cognitive symptom management, and self-reported general health; decreases in health distress, fatigue, and disability; and reduced hospitalizations.1200 To help older clients develop and sustain chronic illness self-management plans, CDSMP:

- •

Explores with clients how having a chronic condition affects them and how, if not properly managed, the condition may interfere with recovery from substance misuse.

- •

Addresses depression and anxiety, often associated with substance misuse and chronic illnesses.

- •

Acknowledges the challenges and successes of daily self-management of symptoms.

- •

Addresses ways to build structure into daily routines to support clients' ability to manage symptoms while emphasizing recovery and wellness activities (e.g., take medication as scheduled, have lunch with a friend, attend AA meetings or other support groups).

- •

Provides information on and links clients to local or online CDSMP services.

- •

Supports clients in their efforts to sustain self-management of symptoms while actively participating in recovery and wellness activities.

To find organizations that offer a licensed CDSMP, go to www.eblcprograms.org/evidence-based/map-of-programs. Also check with the AAA or the Aging and Disability Resource Center (if available) for your community.

The Self-Management Resource Center (www.selfmanagementresource.com) offers a variety of illness self-management programs, including an online program, originally developed by and housed at the Stanford Patient Education Research Center. The Self-Management Resource Center also provides information about training and licensing for organizations that would like to offer a CDSMP.

Clinical Scenario: Promoting Chronic Illness Self-Management

Older adults in recovery from substance misuse who have chronic medical conditions may feel ashamed of having an illness that limits their functioning and ability to engage in recovery activities. The following scenario focuses on an older adult's negative self-judgments about having a chronic medical condition.

- •

AUD Recovery and Chronic Medical Condition: An older adult in long-term recovery from AUD has a chronic medical condition.

- •

Treatment Setting: Hospital-based outpatient behavioral health program

- •

Provider: Licensed psychologist

- •

Treatment Strategies: Foster self-acceptance and promote chronic illness self-management activities.

Ruth is 69 years old, is in long-term AUD recovery, and has attended AA for many years. She lives with her daughter and two grandchildren. Her daughter is divorced and works full time. Ruth watches her grandchildren after school. She became the General Service Representative of her home AA group and sponsored many members over the years. She smoked cigarettes for 20 years. Ruth frequently tells people that “smoking is a bad habit I picked up at meetings.” She recently stopped after she was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Ruth's pulmonologist referred her to counseling at the hospital's outpatient program given her score of 12 on the Patient Health Questionnaire, indicating moderate depression. (Chapter 3 of this TIP offers screening and assessment tools.) She also was not following instructions for managing her COPD.

In counseling, Ruth discloses that she feels ashamed that she has COPD. She stopped going to AA meetings because she feels like a failure for having a chronic medical condition that she says she should have avoided. She also finds it more and more difficult to leave the house. Her energy is low, and she coughs all the time. She also states that she has recently felt like drinking after seeing alcohol commercials on TV.

The provider helps Ruth identify specific self-judgments about COPD. Ruth says, “I hate being sick all the time. I don't want another chronic illness. It's my fault for not taking care of myself. I really failed this time.” The provider helps her reevaluate her perspective about what it means to have a chronic illness and how to manage it, using her experience in recovery as an analogy. The provider says, “You told me that when you first got into recovery, you felt a lot of shame. But you started to feel more accepting when other people talked about alcoholism as a disease that has no cure but can be managed a day at a time.” Ruth tells the provider that she benefited from having a support group to help her learn about her disease, how to accept it, and ways to manage it.

The provider asks Ruth how she quit smoking after 20 years and avoided drinking. She says that she got a nicotine patch and went to a quit smoking group at the hospital. The provider says, “So it seems like you used some of the same tools you used to get sober to stop smoking and stay sober too.” Ruth says, “I guess I'm not such a failure. If I can stay sober for this long and quit smoking after 20 years, I can learn to manage the COPD.”

The provider then explores possible community COPD support resources, including a pulmonary rehabilitation program at the hospital that teaches people about COPD, how to manage their symptoms, and how to save their energy for other activities. Ruth agrees to sign up for the program. She says, “If I can get this thing under control and I have more energy, I'm sure I can get back to my home group. I really miss everyone.”

Ruth and her provider agree to keep meeting while Ruth is in the pulmonary rehabilitation program to monitor her progress and explore any obstacles to returning to AA and staying focused on managing her COPD.

Continuing Care and Relapse Prevention

Continuing care in addiction treatment has traditionally consisted of short-term (e.g., 12-week) outpatient group counseling and passive referral to mutual-help groups. Current thinking about continuing care emphasizes interventions that are long term and flexible enough to adjust to the needs of clients as they move through different stages of recovery.

Staying longer in addiction treatment and having a social support system after treatment that reinforces abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs are two of the most important factors associated with long-term recovery for older adults.1201 Continuing care for older adults should emphasize:

- •

Retention in ongoing treatment and recovery support, including mutual-help group meetings.

- •

Relapse prevention planning.

- •

Use of in-home or telephone counseling as appropriate to strengthen retention and engagement.

- •

Active involvement (with the older adults' permission) of spouses and other family members, or other significant others who support the older adults' recovery.

- •

Active linkage to and follow-up with community-based resources, such as housing and employment services (when needed); senior centers; and fitness, health, and wellness services for older adults.

Also, some individuals find treatment facility alumni programs helpful in supporting their recovery from SUDs. Alumni programs typically offer graduates of the same treatment facility ongoing support through organized activities, continued contact with treatment staff, and further addiction education.

Box

SOCIAL NETWORK COUNSELING.

Relapse prevention planning is an important part of treatment and continuing care. You can facilitate this process by understanding older adult-specific relapse risk factors and strategies for reducing the risk of a return to substance misuse.

Some factors that increase the risk of relapse for older adults who misuse substances1203 include:

- •

Loneliness and isolation.

- •

Boredom.

- •

Chronic pain.

- •

Untreated mental disorders or symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- •

Complicated grief.

- •

Sleep problems.

- •

Lack of social support for recovery.

- •

Chronic medical problems.

- •

Unsafe or unsuitable living environment.

- •

Prolonged stress.

- •

Difficulty managing instrumental ADLs including finances.

- •

Misunderstanding of relapse or lack of a relapse prevention plan.

Support your older clients in maintaining ongoing recovery and reducing the risk of relapse by:1204,1205,1206

- •

Teaching them stress management and coping skills throughout treatment.

- •

Helping them develop or broaden social networks that support recovery.

- •

Developing relapse prevention plans tailored to their individual needs.

- •

Exploring the potential for a return to substance use, normalizing relapse without implying that it is inevitable, and reframing relapse as a learning opportunity.

- •

Reviewing their past success in managing triggers; discussing themes and triggers for past relapses.

- •

Developing plans for reengaging in treatment if they return to substance use before it becomes a full relapse to previous levels of use.

- •

Working with them to evaluate coping strategies and, if needed, retrain on existing strategies or develop new ones.

- •

If appropriate to your role and setting, sustaining long-term supportive contact with them, with the emphasis on helping them maintain stability in recovery and better health and wellness.

Promoting Resilience and Empowerment in Recovery

Interventions that promote resilience can support relapse prevention efforts.1207 Thinking of older adults as inflexible or “set in their ways” is ageist and fails to acknowledge the skills, abilities, and wisdom they have acquired from years of experience. Instead, promote resilience and empower your older clients in recovery from substance misuse by:

- •

Learning about their unique life-course events and challenges.

- •

Tapping into their wisdom.

- •

Supporting them in reflecting on successful resolutions to past challenges they have faced.

- •

Helping them build coping skills to meet the challenges of recovery from substance misuse.

Tasks and Challenges of Aging

Developmental theory suggests that a person has unique, age-specific tasks to master over the life course. The tasks of older adulthood can be challenging, yet rewarding, and include:

- •

Adjusting to decreasing physical health, strength, and cognitive functioning.

- •

Adjusting to retirement and reduced income.

- •

Trying new activities (e.g., creative hobbies limited earlier by career, job, or family responsibilities).

- •

Establishing safe housing and satisfactory living arrangements.

- •

Entering new social roles, including affiliating with one's age group, caring for relatives (particularly relevant for women), and grandparenting.

- •

Adjusting to and accepting the death of a spouse, other family members, or friends.

- •

Finding meaning in life while facing the prospect of death.1208

One way to think about the challenges of aging is to understand that with age comes a broad spectrum of losses and transitions that may be traumatic for the older adult. Work from a perspective of trauma-informed care, which assumes that older clients' presenting issues, behaviors, and emotional reactions may be adaptive responses to trauma or loss and not symptoms of pathology.

The consensus panel recommends that you approach every older adult in SUD treatment or recovery from a trauma-informed and person-centered perspective that recognizes that the experiences of trauma, loss, and grief are highly individualized.

See SAMHSA's TIP 57, Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, for an indepth examination of a trauma-informed approach to the treatment and prevention of addiction and mental illness (https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-57-Trauma-Informed-Care-in-Behavioral-Health-Services/SMA14-4816). See also www.samhsa.gov/trauma-violence.

Despite age-related losses and limitations on physical and cognitive functioning, older adults can experience mental growth and maturation.1209 Most older adults maintain a positive outlook, improve their emotional regulation over time, and express a high degree of life satisfaction. Many older adults rise to the challenge, rediscover themselves, and grow from traumatic or stressful experiences. You can support your older clients in recovery in addressing the tasks and challenges of aging by:

- •

Recognizing that loss and transition are a normal part of aging and helping your older clients identify the losses and transitions specific to them.

- •

Recognizing that your older clients who have experienced the death of a spouse or intimate partner are at higher risk for starting or returning to alcohol misuse or drug use.

- •

Connecting your older clients with recovery supports when the urge to drink or use drugs arises.

- •

Recognizing that multiple losses may trigger trauma reactions in older adults with a history of depression, anxiety, or other mental disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder, and treating co-occurring mental disorders concurrently.

- •

Helping your older clients identify day-to-day coping strategies, including maintaining a regular schedule, which helps people structure activities and maintain participation in social activities.1210

- •

Helping your older clients accept supports and services needed to maximize functioning and independence.

- •

Aiding them in balancing distraction from negative emotions with acceptance and learning to tolerate intense emotions associated with trauma.

- •

Helping clients identify personally relevant strategies for coping with and making meaning of loss and managing normal feelings of grief.

- •

Exploring with them whether reconnecting to a faith community could provide meaning and purpose.

- •

Linking clients in institutional settings (e.g., hospitals, assisted living) to mutual-help groups that provide meetings in such settings, if available.

- •

Helping clients build bridges to new sources of meaning and purpose.1211

- •

Exploring with clients the role adjustments they may face related to retirement; death of a spouse, other family members, friends, or a sponsor; a move to another geographic area; or taking on a parenting role for grandchildren.

- •

Helping clients build and strengthen their support networks.

- •

Encouraging them to explore creative ways to make amends, bring closure to a chapter in their life, celebrate past accomplishments and new developments in their life, or remember a significant other (e.g., creating personally meaningful rituals and ceremonies, writing therapeutic letters, creating memory books).

Strategies for Strengthening Resilience

To help your older clients foster resilience, encourage them to recognize that they can develop cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping skills that strengthen their ability to prevent relapse, manage stress, and rebound from adversity. Bolstering resilience in older adults helps promote healthy aging, improves responses to developmental tasks and challenges, and heightens quality of life.1212 The ability to cope with stressful situations is a key factor in preventing relapse from SUDs (see Resource Alert).

Box

RESOURCE ALERT: STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING RESILIENCE1213.

Collaborative Goal Setting

Collaborative goal setting draws on clients' strengths and focuses on developing attainable goals. This can promote a positive attitude toward changing substance misuse behaviors1214 and create a sense of self-efficacy and hope for older adults in ongoing recovery. Goals should be personally relevant to your older clients, challenging but realistic, achievable, and specific.1215

As a provider, you can facilitate goal setting with your older clients by:

- •

Helping them identify emotionally meaningful goals that support recovery and improve health and wellness (e.g., spending more time with family and friends, maintaining independence or recovery support, aging in place).

- •

Targeting short-term, easily attainable goals that build toward larger goals. For example, to stop alcohol use, help clients identify activities to do instead of drinking (like going out to dinner with a nondrinking friend rather than staying home at night drinking).

- •

Collaborating with your clients to develop a SMART plan (Exhibit 7.4) for achieving the identified substance misuse or wellness goal; the plan should specify a timeframe and any supports clients need to meet the goal.

- •

Monitoring progress toward meeting goals for reducing or stopping substance misuse or engaging in wellness activities.

- •

Helping clients modify goals as needed. Questions you can ask your older clients include:

- –

Was your initial goal too easy or too hard?

- –

Would accomplishing smaller tasks, like reducing your alcohol intake, make it easier to accomplish your ultimate goal of stopping completely?

- –

What obstacles prevented you from achieving or maintaining abstinence?

- –

What obstacles prevented you from starting the wellness activity (e.g., taking a walk every day)?

- –

What are some of your strategies for overcoming these obstacles?

- –

Is your goal still important to you, or is it time to move to a different goal?

Box

EXHIBIT 7.4 Writing a SMART Goal.

Help older clients learn which health and wellness activities will help them prevent return to substance misuse, broaden social networks, build resilience, and give meaning and purpose to ongoing recovery.

Chapter 7 Resources

Provider Resources

A Clinician's Guide to CBT With Older People (www.uea.ac.uk/documents/246046/11919343/CBT_BOOKLET_FINAL_FEB2016%287%29.pdf/280459ae-a1b8-4c31-a1b3-173c524330c9): This workbook explores age-sensitive strategies for adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—Alzheimer's Disease and Healthy Aging (www.cdc.gov/aging/index.html): CDC offers educational materials and resources to help healthcare providers engage in activities of its Healthy Aging Program.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services— Annual Wellness Visit (www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/AWV_chart_ICN905706.pdf): Healthcare providers can use this booklet to learn about the elements of the Health Risk Assessment and the Annual Wellness Visit.

National Council on Aging—Center for Healthy Aging (www.ncoa.org/center-for-healthy-aging): The Center for Healthy Aging provides educational resources for providers on health and wellness, disease management, nutrition, exercise, and fall prevention for older adults.

NIA—Health Topics A-Z (www.nia.nih.gov/health/topics): NIA provides an alphabetical listing of educational resources and information that may be useful for providers when educating older adults on health and wellness topics.

Consumer Resources

Administration on Aging—Eldercare Locator (https://eldercare.acl.gov/Public/Index.aspx): The locator connects older adults and their families to local services.

Eldercare Locator—Expand Your Circles: Prevent Isolation and Loneliness As You Age (https://eldercare.acl.gov/Public/Resources/Brochures/docs/Expanding-Circles.pdf): This easy-to-read brochure offers tips to older adults about expanding their social networks.

National Council on Aging—Resources (www.ncoa.org/audience/older-adults-caregivers-resources/?post_type=ncoaresource): This webpage contains a searchable database of articles, webinars, and other resources.

NIA—Alcohol Use or Abuse (www.nia.nih.gov/health/topics/alcohol-use-or-abuse): This webpage has links to information for older adults and family members about alcohol misuse.

NIA— Older Adults and Alcohol: You Can Get Help (https://order.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-01/older-adults-and-alcohol.pdf): This easy-to-read consumer brochure lays out the issues and answers common questions that older adults have about drinking.

Silver Sneakers—Health and Fitness for Older Adults (www.silversneakers.com): Silver Sneakers connects eligible older adults on some Medicare plans to free memberships at fitness programs across the nation. This website also offers general information about wellness and fitness for older adults.

Chapter 7 Appendix

Assessing Social Support

The Social Network Map is a handy visual tool to help you and your clients identify members of their social network and the types of support they provide.1217 It was developed as a clinical tool for assessing and broadening social support resources for families and has been used in studies to map social networks of older adults and adults with SUDs.1218 The Social Network Map is a client-centered tool that collects information on the composition of older adults' networks, the extent to which network members provide different types of support, and the nature of relationships within the networks.1219 The version depicted below is adapted for use with older adults in recovery.

Adapted from Tracy & Whittaker (1990).1220

The following strategies1221 will help you and your older clients develop a social network map:

- •

Create a pie chart with the seven domains. Health, behavioral health service, social service, and peer recovery support providers may be part of the support network clients identify.

- •

Ask older clients to identify members of their social networks by first name or initials only.

- •

Ask clients to describe how available (e.g., rarely, sometimes, often) each member of the network is to give emotional, instrumental, or informational support. Give examples and be specific:

- –

“Who is available to give you emotional support like comforting you if you are upset or listening if you are stressed?” “How often does this person give you that kind of support?”

- –

“Who is available to help you out in a concrete way like giving you a ride or helping with a chore?” “How often does this person give you that kind of support?”

- –

“Who would give you information on how to do something new or help you make a big decision?” “How often does this person give you that kind of support?”

- •

Note the type and frequency of support each person listed in each domain can offer.

- •

Ask clients to describe how close they are to each member of their network, how long they have known them, and how frequently they see them.

- •

Ask clients to review the map and identify types of support that may be lacking and strategies for adding new network members to beef up their social support.

Assessing Isolation

Assess older adults' level of social isolation and explore all possible sources of social support they have. The Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) is designed for use with older adults. It measures social isolation and focuses on the nature of older adults' relationships with family and friends.1222 Older clients can easily complete the six-item short version (LSNS-6), a self-report questionnaire. The LSNS-6 is available via www.bc.edu/content/bc-web/schools/ssw/sites/lubben/description.html.

For the LSNS-6, the total score (0–30) is an equally weighted sum of the scale's six items. A score below 12 indicates social isolation and need for further assessment.1223 Low scores are associated with increased mortality, hospitalization for all causes, physical health problems, depression and other mental disorders, and low adherence to health-promoting activities.1224 The Modified LSNS-R, with a “family of choice” subscale, was developed for use with lesbian older adults.1225

A screening tool like the LSNS-6 will give you an overall sense of the number of people in an older adult's life who provide support and the level of social isolation or social support the older adult is experiencing. The next step is to explore the kinds of social support older adults have or would like to have. This exploration will help you and your client generate strategies for increasing the diversity of social supports that promote health, wellness, and recovery.

Three types of social support enhance the health of older adults:

- •

Emotional support (e.g., feeling heard and understood, having help with reflecting on one's values, providing a sense that someone cares)

- •

Instrumental support (e.g., helping with finances, transportation, medication adherence)

- •

Informational support (e.g., providing information about community resources or the benefits of wellness and recovery activities, problem-solving, giving advice when asked)1226

Begin your conversation by describing the benefit of social support to people's health and well-being and give examples of the three types of support mentioned above. Then indicate that you would like to ask a few questions to see what kind of support your client already has.

Screening Instruments and Other Tools

The Health Enhancement Lifestyle Profile (HELP) is a validated assessment tool of older adults' habits and routines in health-promoting behaviors in five of the eight dimensions of wellness. It is administered as either a self-report questionnaire or a structured interview.1227 The HELP screening tool is a short version of the comprehensive assessment. It is a 15-item questionnaire that asks for “yes” or “no” responses. It is quick and easy to understand when administered to older adults as a self-report review of health-related lifestyle and wellness factors. (See page 32 of www.csudh.edu/Assets/csudh-sites/ot/docs/3%20Health%20Enhancement%20Lifestyle%20Profile%20(HELP)-Guide%20for%20Clinicians-2016.pdf for the screening tool.) The questions focus on exercise, nutrition, social support, recreational activities, and spirituality.

If further exploration is needed, focus the conversation with the client on items marked “no.” For example, if the client marks “no” on the item about exercise, you might start with a nonjudgmental observation like “I noticed that you normally don't exercise more than twice a week. Exercise can mean different things to different people. Tell me more about what you do for exercise.” This will open a conversation about physical activity and the client's understanding of what exercise is. Build on what the client is already doing before providing information about recommended guidelines or jumping in with advice about how to improve in that area.

The OARS approach is a person-centered communication approach used in motivational interviewing.1228 You can use OARS throughout conversations with clients to help them feel relaxed, understood, and open to thinking about changing their pattern of substance misuse or engaging in wellness activities. Here are some examples of how to apply OARS to your discussions with older clients.

Box

CLINICAL SKILLS: USING OARS IN CLIENT COMMUNICATIONS ON SUBSTANCE MISUSE.

- Chapter 7—Social Support and Other Wellness Strategies for Older Adults - Treati...Chapter 7—Social Support and Other Wellness Strategies for Older Adults - Treating Substance Use Disorder in Older Adults

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...