Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-.

CASRN: 76-99-3

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Maternal use of oral opioids during breastfeeding can cause infant drowsiness, which may progress to rare but severe central nervous system depression. Newborn infants seem to be particularly sensitive to the effects of even small dosages of narcotic analgesics. If the mother of a newborn requires methadone, it is not a reason to discontinue breastfeeding; however, once the mother's milk comes in, it is best to provide pain control with a nonnarcotic analgesic and limit maternal intake of oral methadone to 2 to 3 days. Most infants receive an estimated dose of methadone ranging from 1 to 3% of the mother's weight-adjusted methadone dosage with a few receiving 5 to 6%, which is less than the dosage used for treating neonatal abstinence. Initiation of methadone postpartum or increasing the maternal dosage to greater than 100 mg daily therapeutically or by abuse while breastfeeding poses a risk of sedation and respiratory depression in the breastfed infant, especially if the infant was not exposed to methadone in utero. If the baby shows signs of increased sleepiness (more than usual), breathing difficulties, or limpness, a physician should be contacted immediately. Other agents are preferred over methadone for pain control during breastfeeding.

Women who received methadone maintenance during pregnancy and are stable should be encouraged to breastfeed their infants postpartum, unless there is another contraindication, such as use of street drugs.[1-12] Breastfeeding may decrease, but not eliminate, neonatal withdrawal symptoms in infants who were exposed in utero. Some studies have found shorter hospital stays, durations of neonatal abstinence therapy and shorter durations of therapy among breastfed infants, although the dosage of opiates used for neonatal abstinence may not be reduced.[8,9,11,13-20] The long-term outcome of infants breastfed during maternal methadone therapy for opiate abuse has not been well studied.[21] Abrupt weaning of breastfed infants of women on methadone maintenance might result in precipitation of or an increase in infant withdrawal symptoms, and gradual weaning is advised. The breastfeeding rate among mothers taking methadone for opiate dependency has been lower than in mothers not using methadone in some studies, but this finding appears to vary by institution, indicating that other factors may be important.

Drug Levels

Methadone is metabolized to inactive pyrrolidine and pyrroline metabolites. In adults, methadone oral bioavailability is 80 to 95%.

Maternal Levels. One mother taking 50 mg daily of oral methadone maintenance had milk sampled several times on postpartum days 4 through 8. The highest methadone breastmilk levels (100 and 120 mcg/L) were measured 4 hours after a dose. At 6 and 15 hours after a dose, the level was 40 mcg/L. Lower milk levels (20 and 30 mcg/L) were measured 0 to 3 hours after a dose.[22] Using the peak milk level from this study, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive 18 mcg/kg daily, equal to about 2% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

Ten mothers who were 3 to 10 days postpartum and taking oral methadone maintenance 10 to 80 mg once daily had single milk samples that contained methadone levels ranging from 50 to 570 mcg/L.[23] Using the peak level from this study, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive a maximum of 86 mcg/kg daily of methadone, equal to about 6% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

One mother taking 25 mg daily of oral methadone maintenance had breastmilk sampled twice on postpartum days 5 and 6. The peak methadone milk level was 700 mcg/L on day 5 and 600 mcg/L on day 6, both occurring 3 hours after the dose. Trough levels were about 15 mcg/L on both days.[24]

Two postpartum mothers taking oral methadone maintenance, one 73 mg once daily and the other 30 mg twice daily, had serial milk levels sampled on day 11 and 14 postpartum, respectively. Milk levels ranged from 110 to 180 mcg/L in the first mother and 110 to 250 mcg/L in the second.[25]

One lactating mother taking oral methadone maintenance 45 mg daily had milk sampled several times over the first 4 weeks postpartum and again several times over 24 hours at 6 weeks postpartum. Her colostrum methadone level was 77 mcg/L on the day of delivery and milk levels remained fairly constant (range 77 to 123 mcg/L) throughout the study period. There was little difference in milk levels before and after feeding. Peak milk levels occurred 4 to 6 hours after a dose.[26] Using the range of milk levels reported in this study, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive a maximum of about 12 to 18 mcg/kg daily, equal to 1.6 to 2.4% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

Two mothers, one at 1 week and the other at 3 weeks postpartum, taking oral methadone maintenance (average 0.5 mg/kg daily), had milk levels sampled 4 to 6 times over 8 to 10 hours after a dose. Peak levels were 30 mcg/L and 70 mcg/L, and occurred 1 and 2 hours after the dose, respectively. The half-life of methadone elimination from milk over the collection period was about 8 to 10 hours in both mothers.[27] Using the milk levels reported in this study, calculated average milk levels are about 21 mcg/L and 58 mcg/L, respectively. Using these calculated average milk levels, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive about 3 to 8 mcg/kg daily of methadone, equal to 0.6 to 1.6% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

Twelve breastfeeding mothers, 11 of whom were 3 to 7 days postpartum and 1 who was 26 days postpartum, were taking daily oral methadone maintenance (range 20 to 80 mg daily) and had their milk sampled once before and once after breastfeeding their infants. Milk sampling occurred 2 to 4 hours after a methadone dose. Levels after the feeding tended to be higher than those before. Milk levels tended to be higher with higher maternal doses. The reported average milk level from all 12 mothers was 116 mcg/L (range 39 to 232 mcg/L). Using this average milk level, the authors calculated an average infant dose from breastmilk of 17.4 mcg/kg daily (range 5.9 to 34.8 mcg/kg daily) and an average maternal weight-adjusted dosage of 2.8% (range 1.4 to 5.1%).[28]

Eight breastfeeding mothers who were 3 weeks to 6 months postpartum and taking an average daily dosage of 102 mg of oral methadone maintenance (range 25 to 180 mg) divided twice daily during pregnancy and lactation had their milk sampled 1 to 3 times at 1 to 8 hours after a dose. The reported average milk level of all the samples from all the mothers in this study was 95 mcg/L (range 27 to 260 mcg/L). Milk levels were reportedly not related to methadone dose, but the exact timing of maternal dose and milk levels was not reported. The maximum level reported in this study occurred in a mother taking 55 mg twice daily at 110 days postpartum.[29] Using the maximum milk level reported in this study, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive about 39 mcg/kg daily, equal to about 2% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

Nine breastfeeding mothers taking 22 to 230 mg of daily oral methadone maintenance had their milk sampled prior to their daily dose and several times 1 to 23 hours after the dose. Peak levels appeared to occur 2 hours after the dose. A calculated maximum infant intake of 200 mcg/kg daily was reported. The age of the infants, the individual maternal methadone doses and methadone milk levels were not reported.[30]

Eight breastfeeding mothers who were 1 to 11 days postpartum and taking 40 to 105 mg of oral methadone maintenance once daily during pregnancy and lactation had their milk sampled 6 times over 24 hours after a dose. Average milk levels in each mother were calculated from their multiple samples. The average milk level of all 8 mothers was 237 mcg/L (range 68 to 385 mcg/L). Using each of the mother's average milk level, the authors calculated an average maternal weight-adjusted dosage of 2.8%. Two of these mothers had a milk sampling at 18 and 27 days postpartum. Each was taking 75 mg daily of methadone. Their average milk levels were 254 and 165 mcg/L with an average maternal weight-adjusted dosage of 2.35 and 1.75%, respectively.[31]

Twelve mothers who were taking oral methadone maintenance during pregnancy and postpartum had their milk tested. Each mother collected pre- and post-feed samples by pump or hand expression just before and 3 hours after the daily methadone dose for each of the first 4 days postpartum. Their average methadone dose at delivery was 76 mg daily (range 40 to 100 mg daily). Average pre-feed trough milk levels ranged from 76 to 102 mcg/L; average post-feed trough levels ranged from 65 to 115 mcg/L. Average pre-feed peak milk levels ranged from 128 to 166 mcg/L; average post-feed peak levels ranged from 123 to 200 mcg/L. No relationship was found between maternal dose and milk levels. The authors calculated that an exclusively breastfed infant would receive the following average doses of methadone: 0.006 mg on day 1 postpartum, 0.018 mg on day 2 postpartum, 0.039 mg on day 3 postpartum and 0.084 mg on day 4 postpartum.[32] In a further analysis, 4 women were followed for 90 to 120 days postpartum. No increase in milk concentrations or infant dosage were noted over time, with an average infant intake calculated to be less than 0.33 mg daily.[33]

Three women were taking methadone for narcotic abstinence in doses of 70, 40 and 30 mg daily. Methadone milk concentrations measured before and 4 hours after the doses were in the range of 32 to 146 mcg/L with much lower amounts of the two major methadone metabolites, EDDP and EMDP.[34]

Twenty women who were taking methadone in daily dosages averaging 102 mg (range 40 to 200 mg) had methadone measured in milk samples 1 to 6 days postpartum; 16 of the 20 samples were taken between 1 and 4 hours after a dose at the approximate time of peak milk levels. The authors estimated that the maximum amount that a fully breastfed infant would receive is 20 mcg/kg daily (range 4 to 99) of R-methadone and 13 mcg/kg daily (range 2 to 71) of S-methadone in breastmilk. These amounts were 2.7% and 1.6% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosages of the 2 isomers.[35]

Infant Levels. The 4-week-old infant of a breastfeeding mother taking 45 mg of oral methadone maintenance a day had undetectable (<0.3 mcg/L) serum levels throughout the first 4 weeks of life.[26]

Eight 3- to 7-day-old term infants of mothers taking daily oral methadone maintenance (range 20 to 80 mg daily) had their blood drawn shortly after breastfeeding. Methadone was undetectable (individual assay sensitivity varied from <5 to <30 mcg/L) in 7 of the infants and was 6.5 mcg/L in 1 infant.[28]

Eight breastfed and 8 formula-fed newborn infants whose mothers were receiving methadone maintenance in a median dose of 70 mg daily (range 50 to 105 mg daily) had methadone measured in their plasma on day 14 of life. Concentrations ranged from 2.2 to 8.1 mcg/L compared with maternal plasma concentrations ranging from 134 to 939 mcg/L. No correlation was found between the infant plasma concentrations and their mother's methadone dosage, their breastfeeding status, or whether the infant received treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome.[36]

A 1-year-old infant who was breastfed only during the night had a serum concentration of 2 mcg/L at 12 hours after breastfeeding. Maternal methadone dosage was not specified.[33]

Effects in Breastfed Infants

One center reported 10 women who breastfed during methadone maintenance with no observed adverse effects in their infants.[23]

The death of a 5-week-old infant who was born 1 week prematurely to a former heroin-abusing mother was possibly related to methadone in breastmilk. The infant had been breastfeeding since birth and the mother was taking an unreported daily dose of oral methadone maintenance. The medical examiner's diagnosis was methadone intoxication. A high level of methadone was found in the infant's serum at autopsy; however, the high level might have been caused by postpartum redistribution (which can be 2- to 10-fold[37]). The infant was also noted to be "obviously malnourished." Abnormal brain, liver and other organs on autopsy were also found and it appeared that the infant had been neglected.[38,39]

Three breastfed term infants of mothers taking oral methadone maintenance 45 to 70 mg daily during pregnancy and lactation had no reported adverse effects. They were cared for in a well-baby nursery after birth and discharged in good health home with their mothers at 2 to 3 days of age. At follow up over 3 weeks to 6 months of age, the infants had no symptoms of sedation or methadone withdrawal while breastfeeding. One infant who had breastfeeding discontinued at 3 weeks of age developed withdrawal symptoms of hyperirritability and sleeplessness. The other 2 infants were slowly weaned over 4 to 6 months and did not experience withdrawal upon breastfeeding discontinuation. The authors cautioned against abrupt breastfeeding discontinuation during methadone maintenance.[26]

A partially breastfed 3.5-month-old infant of a mother taking oral methadone maintenance 73 mg once daily died of sudden infant death syndrome. The mother was reportedly mostly bottle feeding the infant due to diminished milk supply. There was no methadone detected in the infant's blood at autopsy (lower limit of the assay not reported).[25]

Twelve full-term breastfed (extent not stated) newborns of mothers taking oral methadone maintenance (range 20 to 80 mg daily) during pregnancy and lactation were observed during their first week of age. Seven of these infants developed methadone withdrawal and 6 required treatment. The authors considered maternal methadone maintenance to be compatible with breastfeeding in the first week of a newborn's life but cautioned that newborn methadone withdrawal may occur despite breastfeeding.[28]

The hospital course of 88 breastfed newborns were compared to 32 non-breastfed newborns. All had mothers who were taking oral methadone maintenance at an average dose of 40 mg daily (range 5 to 175 mg daily). Although the breastfed newborns developed neonatal abstinence syndrome and required rehospitalization after discharge at the same rate as bottle-fed infants, they did have a shorter hospital stay than bottle-fed newborns.[40]

Two fully breastfed term infants of mothers taking oral methadone maintenance 70 and 130 mg daily during pregnancy and lactation had no adverse effects and required no treatment for methadone withdrawal prior to postpartum hospital discharge at 8 and 6 days of age, respectively. Both infants were rehospitalized and treated for methadone withdrawal symptoms at 6 weeks and 17 days of age, respectively, shortly after their mothers abruptly discontinued breastfeeding. The authors surmised that the appearance of symptoms were probably due to withdrawal from methadone in breastmilk.[41]

A Swiss descriptive report found that among the newborns of 84 mothers on methadone maintenance, the neonatal abstinence syndrome was less frequent in breastfed infants than in non-breastfed infants, 26% and 78%, respectively. Twenty-seven infants were breastfed and 54 were formula-fed. "Breastfed" was defined by the authors as more than 50% of feeding from breastmilk while in the hospital.[42]

A 5-week-old breastfed infant became cyanotic and required mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and intubation. The infant's urine was positive for opioids and the infant responded positively to naloxone; the level of consciousness improved over 2 days and extubation was accomplished. The infant's mother admitted to taking methadone and a hydrocodone-acetaminophen combination product that had been prescribed for migraine headache before she was breastfeeding.[43]

A retrospective review from Australia was conducted on the medical records of 190 drug-dependent mothers and their infants. One hundred forty-nine of the mothers were taking methadone at delivery; 62 mothers taking methadone (average dose 68.5 mg daily; maximum dose 150 mg daily) breastfed their infants and 87 mothers taking methadone (average dose 79.6 mg daily) formula-fed their infants. Breastfed infants had a longer median time to withdrawal symptoms (10 days) than formula-fed infants (3 days). Breastfed infants were less likely to require pharmacologic treatment and doses of morphine required to treat withdrawal were lower in breastfed infants. Treatment duration was also shorter in breastfed infants (85 vs. 108 days).[44]

A hospital in England reported outcomes among infants whose mothers were taking methadone maintenance during pregnancy over 2 time periods. Several changes were made in the management of mothers taking methadone between the 2 time periods. In the first time period (1991-1994), only 10% breastfed their infants (4% exclusive); in the second time period (1997-2001), 30% breastfed their infants (20% exclusive). During the second time period, the frequency of jaundice, and convulsions were less frequent in all infants, even though the average maternal methadone dose was twice as high as in the earlier period. Pharmacologic treatment of the infants for withdrawal, days of hospitalization, days in intensive care, and percentage of infants admitted to intensive care were all lower during the second time period.[45]

Eight breastfed and 8 formula-fed newborn infants whose mothers were receiving methadone maintenance in a median dose of 70 mg daily (range 50 to 105 mg daily). No differences were noted between infants in the 2 groups on days 3, 14 or 30 in 9 neurobehavioral measures or on the percentage requiting pharmacologic management of withdrawal.[37] Four of these breastfed infants were followed for 6 months. No health concerns arose during this time. Another infant who was partially breastfed for 1 year had no important health or developmental problems during this time.[33]

A retrospective review of the charts of 68 newborn infants exposed to methadone in utero found that infants who were breastfed had a trend towards requiring shorter durations of treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome, although the trend was not statistically significant.[46]

A retrospective cohort study reviewed the records of 437 newborn infants whose mothers were taking methadone maintenance therapy. Infants who were breastfed for 72 or more hours had a 45% reduced risk of experiencing neonatal abstinence syndrome compared to those who were not. Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more likely in mothers who were also receiving a benzodiazepine.[47]

A 13-month-old infant was being primarily breastfed by a mother who was taking hydrocodone and acetaminophen for pain. On 2 occasions 4 hours apart, she substituted a dose of 40 mg of methadone for the acetaminophen-hydrocodone combination. The child nursed 2 and 6 hours after the second dose for 45 minutes each time, then fell asleep for 45 minutes. Forty-five minutes later, the infant's mother noted that the infant was drowsy and not responsive. Emergency responders confirmed that the baby had cyanosis, myosis, and decreased breathing. Upon arrival at the emergency room, the child was unarousable, but had normal vital signs. The baby awoke after naloxone 0.2 mg was given intravenously. The infant's urine drug screen was positive for opiates, including methadone metabolites. Eighteen hours after the mother's first dose, the infant remained intermittently drowsy with oxygen saturation dropping as low as 91%. During this 18-hour time period, the infant received 4 doses of naloxone intravenously. Eventually, the baby returned to normal state of good health.[48]

A retrospective study in the United States of 128 infants exposed during pregnancy and breastfeeding to methadone found an inverse relationship between the amount of breastfeeding and duration of hospitalization for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Five of the breastfed infants were readmitted for withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing or markedly reducing breastmilk intake after discharge.[13]

A retrospective review of the charts of the infants of mothers taking methadone during pregnancy and postpartum at 2 hospitals in Maine was made. Infants who breastfed (n = 8) had lower neonatal abstinence scores than infants who were formula-fed (n = 9) or had mixed feeding (n = 11).[49]

A retrospective review of the charts of the infants of mothers taking methadone during pregnancy and postpartum at an Ontario Canada hospital was made. Infants who were breastfed (n = 14) had statistically significantly shorter hospital stays than those who were given formula or mixed feeding (n = 118).[14]

A retrospective cohort study of the infants of 354 mothers receiving methadone maintenance in Glasgow, Scotland compared the weight loss of infants who were breastfed to those who were given formula. Infants in the entire breastfed (including partial) group lost a maximum of 10.2% of body weight after birth compared with a weight loss of 8.5% in the formula-fed group and 9.3% in the exclusively breastfed subgroup. Weight loss was less in infants who were small for gestational age compared to infants with normal birth weights. Median maximal weight loss occurred on day 5 postpartum, except for exclusively breastfed infants in whom it occurred on day 4. Neither methadone dose nor polydrug abuse correlated with weight loss. These weight loss values were greater than local values for infants who were not exposed to drugs.[50]

A tertiary care hospital in British Columbia analyzed the charts of 295 women receiving methadone maintenance who delivered an infant over a 39-month period. Infants who were breastfed had a 79% reduced chance of requiring morphine to treat withdrawal symptoms than nonbreastfed infants. All infants were rooming-in, which may have assisted by increasing on-demand feeding and skin-to-skin contact.[51]

A cohort of 124 infants exposed during pregnancy to maternal medication for opioid maintenance therapy were followed postpartum in a Norwegian study. Seventy-eight infants were born to mothers taking methadone. Overall, infants who were breastfed had a lower rate of neonatal abstinence symptoms and a shorter duration of therapy for neonatal abstinence. Among infants exposed to methadone, 53% of breastfed infants and 80% of nonbreastfed infants required treatment. Breastfed infants required treatment for an average of 31 days compared with an average of 49 days among nonbreastfed.[15]

Two infants whose mothers were on methadone maintenance therapy died. Both infants were heterozygous for the lower activity form of the P-glycoprotein transporter, and one had a pharmacogenetic variant for CYP2B6 thought to reduce methadone metabolism. Both also had other factors that could have contributed to their deaths. The authors state that it would inappropriate to assume that methadone from breastmilk was the sole cause of death in thee infants.[37]

A study of pregnant being treated for opiate dependency with methadone at a clinic in Vienna were followed as were their newborn infants. Compared to infants who were not breastfed (n = 118), breastfed infants (n = 48) had lower average measures of neonatal abstinence, lower dosage requirements of morphine (4.35 mg vs 12.65 mg), shorter durations of treatment for neonatal abstinence (8.1 vs 17 days) and shorter hospital stays (17.2 vs 29.4 days).[52]

A retrospective chart review of 194 new mothers who were on methadone maintenance and their infants found that predominant breastfeeding during the first 2 days postpartum delayed the onset on neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in the infants compared to formula feeding. However, breastfeeding did not decrease the need for treatment of the infant for NAS.[53]

A statewide retrospective database study found that infants diagnosed with NAS spent a median of 2 days less in the hospital if they were breastfed than those who were not breastfed.[54]

The results of two multicenter cohort studies were compared. The original study had 86 newborns with neonatal abstinence and the second had 113 infants. All infants had been exposed to methadone or buprenorphine in utero. Infants who were breastfed had a shorter hospitalization by 4.5 to 7.5 days than infants who were not breastfed. Infants who were exposed to buprenorphine had a shorter hospitalization by 4 to 5 days than those exposed to methadone.[55]

A systematic review of studies on the effect of breastfeeding on the outcomes of infants whose mothers were taking methadone during pregnancy and postpartum concluded that breastfeeding was associated with decreased frequency and duration of pharmacologic treatment, shorter hospital length of stay, and decreased severity of NAS.[20]

A search was performed of the shared database of all U.S. poison control centers for the time period of 2001 to 2017 for calls regarding medications and breastfeeding. Of 2319 calls in which an infant was exposed to a substance via breastmilk, 7 were classified as resulting in a major adverse effect, and three of these involved methadone. A one-month-old infant was admitted to the intensive care unit and described as being agitated and irritable and having tremor, respiratory arrest, diarrhea, drowsiness and lethargy. A 13-month-old infant was admitted to the intensive care unit with respiratory depression. A 6-month-old exposed to methadone and benzodiazepines was admitted to the intensive care unit with drowsiness, lethargy, seizure, and tremor. The dosages and extent of breastfeeding were not reported and all of the infants survived.[56]

An infant was born to a mother with opioid use disorder who was taking up to 2 grams of intravenous fentanyl daily. In the hospital she was transitioned to intravenous hydromorphone 120 mg three times daily, oral hydromorphone 32 mg every hour as needed, and methadone 70 mg daily by mouth. After 9 days of tapering the oral morphine dosage, the infant was given 72 mL of the mother’s expressed milk. On day 10, the infant received two doses of 0.1 mg of oral morphine and then breastfed for 30 minutes 3 hours after a maternal dose of 110 mg of intravenous hydromorphone. The infant was alert and active, feeding and sleeping well, and the infant’s morphine was discontinued. There were no clinically relevant episodes of apnea, bradycardia, desaturation, signs of respiratory depression, or excessive sedation. The infant continued to receive formula plus either breastfeeding or expressed milk with no clinically important adverse effects. The mother’s hydromorphone dose was tapered over 47 days while oral methadone and oral slow-release morphine were increased to 190 mg and 1200 mg daily, respectively, and she was discharged on day 58 postpartum. The extent of breastfeeding after hospital discharge was not reported. At 4 months of age, the infant scored above average on all developmental domains.[57]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

Methadone can increase serum prolactin.[58] However, the prolactin level in a mother with established lactation may not affect her ability to breastfeed.

In a French multicenter prospective study of 246 pregnant women in receiving either methadone or buprenorphine for opiate dependency, 93 women were receiving methadone. Twenty-four percent of women receiving methadone breastfed their infants, which was not different from those receiving buprenorphine.[59]

Successful breastfeeding was reported in New Zealand in 15 infants whose mothers were taking methadone for pain and 18 infants whose mothers were taking methadone for maintenance of narcotic abstinence. Both groups of mothers were taking a wide range of doses with median daily dosages of 40 and 60 mg, respectively. An additional 8 infants were bottle-fed and the feeding method was unknown in 2.[60]

A woman who was not breastfeeding, but who had 2 children (breastfeeding history not stated), was prescribed methadone 30 mg daily for heroin dependency. When the dose was increased to 40 mg daily, she developed galactorrhea. Her serum prolactin levels were elevated on 3 occasions over the next year, but all other examinations were normal. Galactorrhea and amenorrhea persisted for at least 2 years with continuous methadone use. The authors of the article stated that 3 cases of hyperprolactinemia had been reported to the United Kingdom's drug regulatory agency. Causality was not proven in any of these cases.[61]

A retrospective chart review of 276 opiate-dependent mothers who delivered in a Baby Friendly Hospital found that mothers taking methadone or buprenorphine for opiate dependency were unlikely to breastfeed their infants. Only 27% of the 132 mothers on methadone maintenance initiated breastfeeding. Of all women in the study, 60% discontinued breastfeeding before discharge from the hospital.[62]

A retrospective cohort study of 150 women enrolled in a substance abuse treatment program found that women taking methadone had a higher prevalence of breastfeeding than women taking buprenorphine plus naloxone. However, this difference appeared to be related to the greater intention to breastfeed before delivery in the methadone group.[63]

A retrospective cohort study of 228 women enrolled in a perinatal substance abuse treatment program found that women taking buprenorphine had a higher prevalence of breastfeeding than women taking methadone. The intention to breastfeed before delivery was similar in both groups. Variations in the prepronociceptin and catechol-O-methyltransferase genes also affected the needed for infant drug treatment for neonatal abstinence.[64]

A small retrospective study of 19 mothers with for opiate use disorder found that mothers who were taking methadone were less likely to breastfeed their infants than mothers taking buprenorphine (29% vs 70%).[65]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

(Analgesia) Acetaminophen, Butorphanol, Fentanyl, Hydromorphone, Ibuprofen, Morphine; (Opiate Dependency) Buprenorphine, Naltrexone

References

- 1.

- Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2014;9:19. [PMC free article: PMC4166410] [PubMed: 25199822]

- 2.

- Kocherlakota P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics 2014;134:e547-61. [PubMed: 25070299]

- 3.

- Mozurkewich EL, Rayburn WF. Buprenorphine and methadone for opioid addiction during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2014;41:241-53. [PubMed: 24845488]

- 4.

- Sutter MB, Leeman L, Hsi A. Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2014;41:317-34. [PubMed: 24845493]

- 5.

- Lefevere J, Allegaert K. Question: is breastfeeding useful in the management of neonatal abstinence syndrome? Arch Dis Child 2015;100:414-5. [PubMed: 25784740]

- 6.

- Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: Guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med 2015;10:135-41. [PMC free article: PMC4378642] [PubMed: 25836677]

- 7.

- Cleveland LM. Breastfeeding recommendations for women who receive medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders: AWHONN Practice Brief Number 4. Nurs Womens Health 2016;20:432-4. [PubMed: 27520608]

- 8.

- McQueen K, Murphy-Oikonen J. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2468-79. [PubMed: 28002715]

- 9.

- Holmes AP, Schmidlin HN, Kurzum EN. Breastfeeding considerations for mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:861-9. [PubMed: 28488805]

- 10.

- Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e81-e94. [PubMed: 28742676]

- 11.

- Bogen DL, Whalen BL. Breastmilk feeding for mothers and infants with opioid exposure: What is best? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;24:95-104. [PubMed: 30922811]

- 12.

- Harris M, Schiff DM, Saia K, et al. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #21: Breastfeeding in the setting of substance use and substance use disorder (Revised 2023). Breastfeed Med 2023;18:715-33. [PMC free article: PMC10775244] [PubMed: 37856658]

- 13.

- Isemann B, Meinzen-Derr J, Akinbi H. Maternal and neonatal factors impacting response to methadone therapy in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Perinatol 2011;31:25-9. [PubMed: 20508596]

- 14.

- Pritham UA, Paul JA, Hayes MJ. Opioid dependency in pregnancy and length of stay for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012;41:180-90. [PMC free article: PMC3407283] [PubMed: 22375882]

- 15.

- Welle-Strand GK, Skurtveit S, Jansson LM, et al. Breastfeeding reduces the need for withdrawal treatment in opioid-exposed infants. Acta Paediatr 2013;102:1060-6. [PubMed: 23909865]

- 16.

- Meites E. Opiate exposure in breastfeeding newborns. J Hum Lact 2007;23:13. [PubMed: 17293546]

- 17.

- Philipp BL, Merewood A, O'Brien S. Methadone and breastfeeding: New horizons. Pediatrics 2003;111:1429-30. [PubMed: 12777563]

- 18.

- Oei J, Lui K. Management of the newborn infant affected by maternal opiates and other drugs of dependency. J Paediatr Child Health 2007;43:9-18. [PubMed: 17207049]

- 19.

- MacVicar S, Humphrey T, Forbes-McKay KE. Breastfeeding and the substance-exposed mother and baby. Birth 2018;45:450-8. [PubMed: 29411890]

- 20.

- McQueen K, Taylor C, Murphy-Oikonen J. Systematic review of newborn feeding method and outcomes related to neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2019;48:398-407. [PubMed: 31034790]

- 21.

- Wachman EM, Schiff DM, Silverstein M. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 2018;319:1362-74. [PubMed: 29614184]

- 22.

- Kreek MJ, Schecter A, Gutjahr CL, et al. Analyses of methadone and other drugs in maternal and neonatal body fluids: Use in evaluation of symptoms in a neonate of mother maintained on methadone. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1974;1:409-19. [PubMed: 4619541]

- 23.

- Blinick G, Inturrisi CE, Jerez E, Wallach RC. Methadone assays in pregnant women and progeny. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975;121:617-21. [PubMed: 1115163]

- 24.

- Kreek MJ. Methadone disposition during perinatal period in humans. Pharmcol Biochem Behav 1979;11 (Suppl):7-13. [PubMed: 550136]

- 25.

- Geraghty B, Graham EA, Logan B, Weiss EL. Methadone levels in breast milk. J Hum Lact 1997;13:227-30. [PubMed: 9341416]

- 26.

- Robinson JS, Catlin DH, Barrett CT. Withdrawal from methadone by breast feeding. Stern L et al, eds Intensive care in the Newborn, III Masson 1979:213-8.

- 27.

- Pond SM, Kreek MJ, Tong TG, et al. Altered methadone pharmacokinetics in methadone-maintained pregnant women. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1985;233:1-6. [PubMed: 3981450]

- 28.

- Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;44:543-7. [PMC free article: PMC2042880] [PubMed: 9431829]

- 29.

- McCarthy JJ, Posey BL. Methadone levels in human milk. J Hum Lact 2000;16:115-20. [PubMed: 11153342]

- 30.

- Ho T, Selby P, Kapur B, Ito S. Pharmacokinetics of methadone in breast milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001;69:P51. doi:10.1016/S0009‐9236(01)90087‐6a [CrossRef]

- 31.

- Begg EJ, Malpas TJ, Hackett LP, Ilett KF. Distribution of R- and S-methadone into human milk during multiple, medium to high oral dosing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:681-85. [PMC free article: PMC2014565] [PubMed: 11736879]

- 32.

- Jansson LM, Choo RE, Harrow C, et al. Concentrations of methadone in breast milk and plasma in the immediate perinatal period. J Hum Lact 2007;23:184-90. [PMC free article: PMC2718050] [PubMed: 17478871]

- 33.

- Jansson LM, Choo R, Velez ML, et al. Methadone maintenance and long-term lactation. Breastfeed Med 2008;3:34-7. [PMC free article: PMC2689552] [PubMed: 18333767]

- 34.

- Nikolaou PD, Papoutsis II, Maravelias CP, et al. Development and validation of an EI-GC-MS method for the determination of methadone and its major metabolites (EDDP and EMDP) in human breast milk. J Anal Toxicol 2008;32:478-84. [PubMed: 18713515]

- 35.

- Bogen DL, Perel JM, Helsel JC, et al. Estimated infant exposure to enantiomer-specific methadone levels in breastmilk. Breastfeed Med 2011;6:377-84. [PMC free article: PMC3228593] [PubMed: 21348770]

- 36.

- Jansson LM, Choo R, Velez ML, et al. Methadone maintenance and breastfeeding in the neonatal period. Pediatrics 2008;121:106-14. [PubMed: 18166563]

- 37.

- Madadi P, Kelly LE, Ross CJ, et al. Forensic investigation of methadone concentrations in deceased breastfed infants. J Forensic Sci 2016;61:576-80. [PubMed: 26513313]

- 38.

- Smialek JE, Monforte JR. Toxicology and sudden infant death. J Forensic Sci 1977;22:757-62. [PubMed: 618000]

- 39.

- Smialek JE, Monforte JR, Aronow R, Spitz WU. Methadone deaths in children: A continuing problem. JAMA 1977;238:2516-7. [PubMed: 578886]

- 40.

- Malpas TJ, Horwood J, Darlow BA. Breastfeeding reduces the severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health 1997;33:A38 P20.

- 41.

- Malpas TJ, Darlow BA. Neonatal abstinence syndrome following abrupt cessation of breastfeeding. N Z Med J 1999;112:12-3. [PubMed: 10073159]

- 42.

- Arlettaz R, Kashiwagi M, Das-Kundu S, et al. Methadone maintenance program in pregnancy in a Swiss perinatal center (II): Neonatal outcome and social resources. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:145-50. [PubMed: 15683374]

- 43.

- Meyer D, Tobias JD. Adverse effects following the inadvertent administration of opioids to infants and children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44:499-503. [PubMed: 16015396]

- 44.

- Abdel-Latif ME, Pinner J, Clews S, et al. Effects of breast milk on the severity and outcome of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants of drug-dependent mothers. Pediatrics 2006;117:e1163-9. [PubMed: 16740817]

- 45.

- Miles J, Sugumar K, Macrory F, et al. Methadone-exposed newborn infants: Outcome after alterations to a service for mothers and infants. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:206-12. [PubMed: 17291325]

- 46.

- Lim S, Prasad MR, Samuels P, et al. High-dose methadone in pregnant women and its effect on duration of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:70.e1-5. [PubMed: 18976737]

- 47.

- Dryden C, Young D, Hepburn M, Mactier H. Maternal methadone use in pregnancy: Factors associated with the development of neonatal abstinence syndrome and implications for healthcare resources. BJOG 2009;116:665-71. [PubMed: 19220239]

- 48.

- West PL, Mckeown NJ, Hendrickson RG. Methadone overdose in a breast-feeding toddler. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:721. doi:10.1080/15563650903076924 [CrossRef]

- 49.

- McQueen KA, Murphy-Oikonen J, Gerlach K, Montelpare W. The impact of infant feeding method on neonatal abstinence scores of methadone-exposed infants. Adv Neonatal Care 2011;11:282-90. [PubMed: 22123351]

- 50.

- Dryden C, Young D, Campbell N, Mactier H. Postnatal weight loss in substitute methadone-exposed infants: Implications for the management of breast feeding. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F214-6. [PubMed: 20656717]

- 51.

- Hodgson ZG, Abrahams RR. A rooming-in program to mitigate the need to treat for opiate withdrawal in the newborn. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:475-81. [PubMed: 22555142]

- 52.

- Metz VE, Comer SD, Pribasnig A, et al. Observational study in an outpatient clinic specializing in treating opioid-dependent pregnant women: Neonatal abstinence syndrome in infants exposed to methadone-, buprenorphine- and slow-release oral morphine. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl 2015;17:5-15. https://www

.heroinaddictionrelatedclinicalproblems .org/harcp-archives .php?year=2015 - 53.

- Liu A, Juarez J, Nair A, Nanan R. Feeding modalities and the onset of the neonatal abstinence syndrome. Front Pediatr 2015;3:14. [PMC free article: PMC4341509] [PubMed: 25767791]

- 54.

- Short VL, Gannon M, Abatemarco DJ. The association between breastfeeding and length of hospital stay among infants diagnosed with neonatal abstinence syndrome: A population-based study of in-hospital births. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:343-9. [PubMed: 27529500]

- 55.

- Wachman EM, Hayes MJ, Sherva R, et al. Association of maternal and infant variants in PNOC and COMT genes with neonatal abstinence syndrome severity. Am J Addict 2017;26:42-9. [PMC free article: PMC5206487] [PubMed: 27983768]

- 56.

- Beauchamp GA, Hendrickson RG, Horowitz BZ, Spyker DA. Exposures through breast milk: An analysis of exposure and information calls to U.S. poison centers, 2001-2017. Breastfeed Med 2019;14:508-12. [PubMed: 31211594]

- 57.

- Patricelli CJ, Gouin IJ, Gordon S, et al. Breastfeeding on injectable opioid agonist therapy: A case report. J Addict Med 2022;7:222-6. [PMC free article: PMC10022656] [PubMed: 36001061]

- 58.

- Tolis G, Dent R, Guyda H. Opiates, prolactin, and the dopamine receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1978;47:200-3. [PubMed: 263291]

- 59.

- Lejeune C, Aubisson S, Simmat-Durand L, et al. [Withdrawal syndromes of newborns of pregnant drug abusers maintained under methadone or high-dose buprenorphine: 246 cases]. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 2001;152 (Suppl 7):21-7. [PubMed: 11965095]

- 60.

- Sharpe C, Kuschel C. Outcomes of infants born to mothers receiving methadone for pain management in pregnancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004;89:F33-6. [PMC free article: PMC1721632] [PubMed: 14711851]

- 61.

- Bennett J, Whale R. Galactorrhoea may be associated with methadone use. BMJ 2006;332:1071. [PMC free article: PMC1458551] [PubMed: 16675813]

- 62.

- Wachman EM, Byun J, Philipp BL. Breastfeeding rates among mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Breastfeed Med 2010;5:159-64. [PubMed: 20658895]

- 63.

- Gawronski KM, Prasad MR, Backes CR, et al. Neonatal outcomes following in utero exposure to buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone. SAGE Open Med 2014;2:2050312114530282. [PMC free article: PMC4607220] [PubMed: 26770721]

- 64.

- Yonke N, Maston R, Weitzen S, Leeman L. Breastfeeding intention compared with breastfeeding postpartum among women receiving medication-assisted treatment. J Hum Lact 2019;35:71-9. [PubMed: 29723483]

- 65.

- Skiba B, Feldman A. Factors associated with breastfeeding among mothers being treated with opiates. J Invest Med 2022;70:1191. doi:10.1136/jim-2022-ERM.275 [CrossRef]

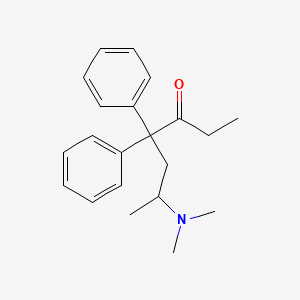

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Methadone

CAS Registry Number

76-99-3

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

- User and Medical Advice Disclaimer

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Record Format

- LactMed - Database Creation and Peer Review Process

- Fact Sheet. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Glossary

- LactMed Selected References

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - About Dietary Supplements

- Breastfeeding Links

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Fentanyl.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Fentanyl.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Hydrocodone.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Hydrocodone.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Oxymorphone.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Oxymorphone.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Tapentadol.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Tapentadol.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Piritramide.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Piritramide.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Methadone - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)Methadone - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...