NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life; Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004.

Rodney Clark

Numerous indices could be used to characterize health status in the later years. These indices include mortality (e.g., all causes, life expectancy, heart diseases, malignant neoplasms, and cerebrovascular diseases), chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension and cancer), and subjective health status. Many of the major racial (Asian, black, Native American, Pacific Islander, and white) and ethnic (Hispanic) groups in the United States, heretofore referred to as ethnic groups, differ with respect to these health indices. For example, research indicates that relative to their peers in other ethnic groups, more seasoned blacks (65 to 84 years of age) have shorter life expectancies, poorer subjective health, higher rates of hypertension, and higher death rates from all causes, heart diseases, malignant neoplasms, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 1998; Pamuk, Makuc, Heck, Reuben, and Lochner, 1998; Pappas, Queen, Hadden, and Fisher, 1993). With one rather consistent exception of non-Hispanic white males having higher mortality rates than black males in the oldest age group (85 years and older), the observation of poorer health profiles for black males and females tended to persist, even after stratifying by socioeconomic status. Among the other ethnic groups, non-Hispanic whites generally had the second poorest profiles, with Hispanics having the most favorable profiles and Asians or Pacific Islanders and Native Americans having intermediary profiles. Notable exceptions to this trend include age-adjusted death rates for chronic liver disease/cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus, where Native Americans have the highest and second highest mortality rates.

If these ethnic group disparities in health are not secondary to genetic or biological differences between the ethnic groups (American Anthropological Association, 1998; Barnett et al., 2001; Casper et al., 2000; Lewontin, 1995; Lieberman and Jackson, 1995; Williams, 1997), to what could the ethnic group disparities in health be attributed? Recent research suggests that behavioral risk profiles (NCHS, 1998) as well as direct and indirect effects of environmental and sociopolitical conditions are among the factors that contribute to these health disparities (Smith, Shipley, and Rose, 1990; Tennstedt and Chang, 1998). Racism is one environmental and sociopolitical condition that might help to explain the persisting disparities (Barnett et al., 2001; Casper et al., 2000; Krieger, 1999). The primary purpose of this chapter is to examine probable associations between racism and interethnic group health differences in the later years. Toward this end, the first section explores the ways in which racism has been conceptualized. In the context of a proposed conceptual model, the second section reviews research investigating the relationship of racism to different indices of health, and the final section highlights several directions for future research.

CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF RACISM

Throughout this chapter, racism is used to refer to “beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics [e.g., skin color, hair texture, width of nose, size of lips] or ethnic group affiliation” (Clark, Anderson, Clark, and Williams, 1999, p. 805). Defined in this way, racism can exist at both the individual and institutional levels and include subjective and more objective experiences of racism. Consistent with Clark et al. (1999), perceived racism involves perceptions of prejudiced attitudes and discriminatory behaviors, and is not limited to more overt expressions of behaviors (e.g., being called a “nigger”). That is, perceived racism may also include perceptions of subtler forms of racism (e.g., symbolic beliefs and behaviors) (McConahay and Hough, 1976; Sears, 1991; Yetman, 1985). Although perceived racism will be the focus of this chapter, institutional racism (discussed in detail elsewhere in this volume), which may not be perceived, is also included, given its complex and often overlooked relationship to perceived racism and health status.

Although several terms have been used in the scientific literature to describe perceived racism, it is important to note that using the definition of racism forwarded by Clark et al. (1999), perceived racism is not necessarily characterized by feelings of racial superiority, an ethnic group's control over valued resources, or the power of an ethnic group to impose its beliefs and values on others. Any member of a given ethnic group has the capacity to be racist against members of other ethnic groups (interethnic group racism) or against members of their own ethnic group (intraethnic group racism; also referred to as “colorism” by Hall [1992]). Because perceived racism is conceptualized herein as an umbrella term that includes prejudice and discrimination, it differs from other conceptualizations that describe racism as an ideologically based set of beliefs that direct relationships between oppressed and nonoppressed groups (Jones, 1997). Additionally, because relationships between ethnic groups are emphasized, racism perpetuated by members within an ethnic minority group is nonexistent.

Although a large body of research has examined the prevalence of interethnic group racism (both institutional and individual), relatively few have explored the existence of intraethnic group racism—a likely byproduct of how racism has been conceptualized to date in the scientific literature (Clark, in press). Among the limited number of studies exploring the existence of intraethnic group racism, research suggests that U.S. blacks once endorsed the idea of lighter skinned superiority (Gatewood, 1988; Okazawa-Rey, Robinson, and Ward, 1986) and routinely blocked darker skinned blacks from valued resources (e.g., matriculation at select historically black colleges and universities, as well as membership in some predominantly black fraternities and sororities, churches, and social/business organizations) (Neal and Wilson, 1989; Okazawa-Rey et al., 1986). Published research investigating the independent effects of intraethnic group racism, as well as the interactive or additive effects of intraethnic group racism and interethnic group racism, on health has yet to be published.

Jones (1972, p. 131) described institutional racism as “established laws, customs, and practices, which systematically reflect and produce racial inequities in American society.” The institutionalization of these laws, customs, and practices are significant because their “effects are widespread and because they can result either from overt racism by an individual, or from a negative race-based policy, or as a systematic racial effect of a bias-free practice or policy” (Jones, 1997, p. 437). Institutional racism, whether overt/covert or intentional/unintentional, refers to social conditions such as residential segregation, occupational steering, and racial profiling. These social conditions in turn are posited to contribute to (1) socioeconomic disparities, (2) greater exposure to hazards (e.g., dangerous jobs and toxic environments), (3) coping responses, and (4) perceptions of unfair treatment and injustices—all of which may influence health (Bird and Bogart, 2001; Charatz-Litt, 1992; Cooper, 2001; Ferguson et al., 1998; Fernando, 1984; Jackson, Anderson, Johnson, and Sorlie, 2000; Kennedy, Kawachi, Lochner, Jones, and Prothrow-Stith, 1997; Klassen, Hall, Saksvig, Curbow, and Klassen, 2002; Landrine and Klonoff, 2000; Polednak, 1996; Utsey, Payne, Jackson, and Jones, 2002; Williams and Collins, 1995).

PERCEIVED RACISM AND HEALTH DISPARITIES: A PROPOSED MODEL

Racism as a Source of Stress

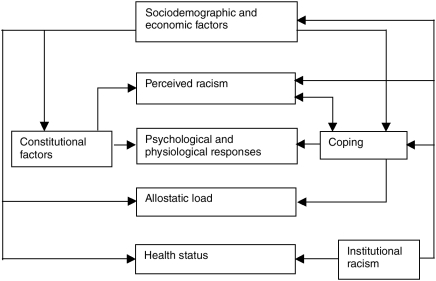

An emerging body of research indicates that racism (whether or not it is perceived) is a potential source of acute and chronic stress for many ethnic group members (Clark, in press; Harrell, 2000; Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams, 1999; Krieger, 1999; Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, and Rummens, 1999; Utsey and Ponterotto, 1996; Williams and Neighbors, 2001), including Caucasians (Williams, 1997b). As an additional source of stress, individual and institutional racism may contribute to interethnic group and intraethnic group disparities in health via distal and proximal pathways (Figure 14-1). Distal pathways include internal and external factors that are hypothesized to mediate the relationship between environmental events and perceptions of these events as involving racism and involving harm, a threat, or a challenge. Importantly, the subjective component of perceived racism precludes an a priori determination of stressfulness (i.e., perception of harm, a threat, or a challenge). Proximal pathways, on the other hand, are postulated to influence psychological (e.g., anger) and physiological (e.g., sympathetic nervous system and immune activity) stress responses or tertiary outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular disease, depression, low birthweight, and cancer) more directly.

Building on existing conceptualizations proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), McEwen (1998), and Clark et al. (1999), the underlying premise of this proposed model is that perceptions of an environmental stimulus as involving racism and involving harm, a threat, or a challenge are mitigated by sociodemographic factors, constitutional factors, and coping resources. Once the stimulus is perceived as involving racism and involving harm, a threat, or a challenge, psychological and physiological stress responses will result, followed by coping responses. Over time, the repeated activation and adaptation of these psychological and physiological systems are posited to lead to an allostatic burden, which, in turn, increases the risk of negative health outcomes (McEwen and Seeman, 1999). To the extent that (1) perceived racism evokes psychological and physiological responses with which people cope, and (2) the differential allostatic burden associated with perceived racism is observed along ethnic-gender lines, this model may provide a more context-specific framework for understanding the relationship between perceived racism and health disparities in the later years. Although it is probable that perceptions of discrimination associated with other “isms” (e.g., ageism, classism, and sexism), as well as perceptions of other stressors (e.g., acculturative stress), are related in similar ways to psychological and physiological functioning, this chapter will be relegated to a discussion of ethnically based injustices and inequities.

Sociodemographic and Economic Factors

Ethnicity

Research conducted in various countries indicates that ethnically based injustices and inequities are evident across different ethnic groups (Collier and Burke, 1986; Gilvarry et al., 1999; Karlsen and Nazroo, 2002; Lowell, Teachman, and Jing, 1995; McKeigue, Richards, and Richards, 1990; Sakamoto, Wu, and Tzeng, 2000; Villarruel, Canales, and Torres, 2001), which may have implications for health among Southeast Asian refugees in Canada (Noh et al., 1999), Asian-American Vietnam veterans in the United States (Loo et al., 2001), Southeast Asian refugees and Pacific Islander immigrants in New Zealand (Pernice and Brook, 1996), former Soviet immigrants in the United States (Aroian, Norris, Patsdaughter, and Tran, 1998), Chinese Canadians in Canada (Pak, Dion, and Dion, 1991; Tang and Trovato, 1998), Chinese Americans in the United States (Gee, 2002), Native Americans in the United States (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, and Stubben, 2001), Latin Americans in Australia (McDonald, Vechi, Bowman, and Sanson-Fisher, 1996), Aboriginals in Australia (Lowe, Kerridge, and Mitchell, 1995), and Mexican Americans in the United States (Finch, Kolody, and Vega, 2000).

In the United States, blacks are disproportionately exposed to environmental stimuli that might be perceived as involving racism (Collier and Burke, 1986; James, 1993; Jones, 1997; Krieger, 1999; Krieger, Sidney, and Coakley, 1998; Outlaw, 1993; Sears, 1991; Sigelman and Welch, 1991; Utsey, 1998). Although members of other ethnic groups report experiences of racism in the United States (Aroian et al., 1998; Finch et al., 2000; Krieger, 1990; Krieger and Sidney, 1996; Whitbeck et al., 2001; Williams, Yu, Jackson, and Anderson, 1997b), the sociopolitical history of racism in the United States as it relates to blacks (e.g., statement regarding slaves in the U.S. Constitution) has been more pervasive (James, 1993; Jones, 1997) and has contributed to acute and chronic perceptions that may be especially toxic for blacks (Cooper, 1993). In a multistage probability sample of 1,139 black and white adults (18 years and over) in three counties in southeastern Michigan, Williams et al. (1997a) found that blacks were nearly 10 times more likely to attribute perceptions of unfair treatment to ethnicity. Additionally, blacks were four times more likely to report ever being treated unfairly because of their ethnicity compared to whites. These attributions were positively related to chronic health conditions, and lifetime experiences of racism were positively associated with bed days and chronic health conditions in black but not white adults. Were these findings to be replicated among persons in the later years, and were the cumulative psychological and physiological effects of perceived racism associated with coping resources and allostatic burden, a more informed understanding of probable contributors to the health divide in the later years might be evinced.

Socioeconomic Status

Research indicates that socioeconomic status (SES) is one of the strongest predictors of health status (Krieger, Rowley, Herman, Avery, and Phillips, 1993; Marmot, Kogevinas, and Elston, 1987; Williams and Collins, 1995). Although space limitations preclude a detailed discussion of the direct and indirect effects of SES and health status, several reports have discussed these relationships and are suggested for further reading (Anderson and Armstead, 1995; Kaufman, Long, Liao, Cooper, and McGee, 1998; Krieger, 1999; Krieger et al., 1993; Marmot et al., 1987; NCHS, 1998; West, 1997; Whitfield, Weidner, Clark, and Anderson, 2002; Williams and Collins, 1995). Per the proposed model, SES differences could influence health disparities directly or indirectly. As an example of the former, secondary to sociopolitical conditions such as institutional racism, black elders are disproportionately represented in lower SES groups (Pamuk et al., 1998). Accordingly, they would be more likely to experience financial barriers to health care (beyond that provided by Medicare, e.g., out-of-pocket expenses for deductibles and co-payments) (McBean and Gornick, 1994) and reside in areas with limited access to quality health services and personnel, leading to elevated morbidity and mortality rates.

If the SES associated with institutional racism is related to elevated morbidity and mortality in some black elders, what accounts for their ability not to succumb to these ailments in young and middle adulthood? Cross-sectional data suggest that many chronic health conditions observed in young and middle adulthood persist into late adulthood, thereby contributing to higher rates of major activity limitations and higher percentages of respondent-assessed fair and poor health observed among blacks (65 years of age and older) compared to their white counterparts (NCHS, 1998). Regarding mortality, the cumulative effects of perceived racism probably do not lead to physiological exhaustion until the associated allostatic burden has taken its toll in late adulthood.

SES might also affect ethnic group health disparities indirectly via its relationship to the quantity and type of racist stimuli to which individuals are exposed, constitutional factors, and coping resources. For example, the equivocal findings with regard to the relationship between SES and the prevalence of racism (Gary, 1995; Landrine and Klonoff, 1996; Sigelman and Welch, 1991) probably are secondary to the dimension of racism assessed, with higher and lower SES blacks having greater exposures to subtle and overt forms of racism, respectively (Clark et al., 1999). To the extent that the magnitude of psychological and physiological stress responses are similar for overt and more subtle forms of perceived racism, contributing to comparable allostatic burdens, the deleterious effects of perceived racism would be observed across SES groups among those disproportionately exposed to environmental stimuli perceived as involving racism and involving harm, a threat, or a challenge. This interpretation is consistent with the observation that many ethnic disparities in health persist after adjusting for SES.

Age

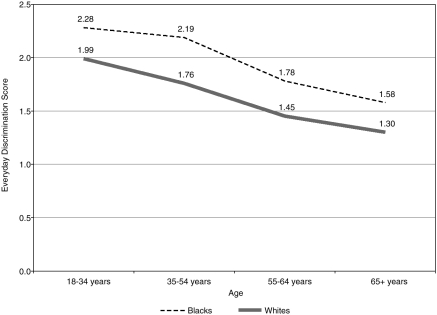

Age is another sociodemographic factor that is rather consistently related to health status, with more seasoned persons being at greater risk for negative health outcomes (NCHS, 1998). In addition to its relationship to health status, age is also related to the frequency with which blacks and whites (Bledsoe, Combs, Sigelman, and Welch, 1996), as well as Southeast Asian refugees (Noh et al., 1999), perceive racism. For example, Forman, Williams, and Jackson (1997) found that perceptions of lifetime discrimination (e.g., “Do you think that you have ever been unfairly stopped, searched, questioned, physically threatened or abused by the police?”), recent discrimination (same as lifetime discrimination questions, except exposure is limited to the past 12 months), and everyday discrimination (e.g., “In your day-to-day life how often have any of the following things happened to you: You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores?”) decreased with advancing age in blacks and whites. Relative to the older age cohort (65+ years of age), for instance, blacks and whites in the youngest age cohort (18 to 34 years) had scores on the measure of everyday discrimination that were 44 percent and 53 percent higher (blacks and whites, respectively) (Figure 14-2). Despite decreases in reports of discrimination across the two ethnic groups, black-white differences in these reports remained consistent across the four age groups. However, the direction of these relationships has varied. Although some studies have found positive relationships between age and perceived racism/discrimination (Sigelman and Welch, 1991), the association in other studies has been negative (Adams and Dressler, 1988; Forman et al., 1997; Gary, 1995), and the relationship in still other investigations has been curvilinear (with the apex occurring during middle adulthood) (Forman et al., 1997; Schuman and Hatchett, 1974). The observed black-white differences with respect to perceived discrimination should be interpreted cautiously in the Forman et al. (1997) study, given that participants were not instructed to limit their reports to ethnic group discrimination. Therefore, it is possible that whites were reporting on experiences of discrimination that they perceived as being secondary to their gender, sexual orientation, SES, or weight. Although the discrimination scores for blacks probably were also inflated with respect to perceived ethnic discrimination—as opposed to discrimination from all causes—research indicates that blacks overwhelmingly attribute such unfair treatment to racism, whereas whites do not (Williams et al., 1997b).

To address the curvilinear relationship they observed between age and subjective experiences of racism, Schuman and Hatchett (1974) reasoned that higher reports of racism during middle adulthood, relative to early and late adulthood, might reflect their greater exposure to workplace discrimination. Studies that have found an inverse association between age and perceptions of racism should not necessarily be interpreted as meaning that black elders habituate (psychologically or physiologically) to perceptions of racism. In addition to habituation, several explanations are plausible. First, in the later years, blacks may come to accept racism as a way of life and not attribute the unfair treatment to racism (Adams and Dressler, 1988). Second, because of their disproportionate exposure to racist stimuli, more seasoned blacks may have come to use racism-specific coping strategies (e.g., anticipatory coping) that mitigate the negative psychological effects associated with these stimuli (Essed, 1991). As a result, they may not perceive the stimulus as being stressful or involving as much stress (e.g., possibly secondary to habituation) as their white counterparts. Third, given that blacks who are 65 and older were teenagers and young adults before and just after the Civil Rights Movement, it is also probable that by comparison, black elders do not consider many of the subtler forms of racism prevalent in the United States today as involving the same type of racism to which many of them may have been exposed. Thus, they may not perceive these more subtle forms of racism as really involving racism. Finally, if blacks in the later years use denial (i.e., not reporting perceptions of racism) as a way of coping with the untoward effects associated with their higher perceptions of racism (Forman et al., 1997), and if this method of coping is used repeatedly to deal with perceived racism or is associated with prolonged psychological or physiological reactivity, a greater allostatic burden would be expected to develop in this group (Krieger, 1999; McEwen and Seeman, 1999). Although speculative, this increased allostatic burden may contribute to more negative health profiles among blacks in the later years.

Gender

With the exception of health outcomes that occur in an inordinately higher frequency in one gender group (e.g., breast and prostate cancer), females generally have more favorable health profiles than males across ethnic and socioeconomic groups (Barnett et al., 2001; Casper et al., 2000; NCHS, 1998; Pamuk et al., 1998). Exceptions to this general trend include higher cerebrovascular mortality rates for black and white females (relative to males) who are 85 years and over, and higher hypertension prevalence rates for females (relative to males) who are 55 years and over. Similar to the observed relationships between age and perceived racism, the findings with respect to gender and perceived racism have been mixed, with some research showing that black males and females perceive equal amounts of racism (Landrine and Klonoff, 1996) and other investigations indicating that black men perceive more racism than black women (Sigelman and Welch, 1991; Utsey et al., 2002). In one study of black and white adults, Forman et al. (1997) used two indices to measure major perceptions of discrimination: lifetime discrimination and recent (past 12 months) discrimination. They found that black males and white males perceived more discrimination than black females and white females, respectively, although the gender effect was stronger in blacks. In another study using a more seasoned sample of blacks (mean age = 71.62 years), Utsey et al. (2002) assessed perceptions of cultural, institutional, individual, and collective racism. Their findings indicated that the stress associated with perceptions of institutional and collective racism was significantly higher for black males relative to black females. These findings, coupled with the previously mentioned observations that blacks perceive more racism than whites, suggest that black males may be the most vulnerable to the allostatic burden associated with perceived racism—a pattern that mirrors the health risk profiles of black males (highest risk).

Constitutional

The constitutional factors are qualities with which people are born, and include genes, skin tone, and family history of disease (e.g., hypertension, cancer, heart disease, and psychological disorders). These factors are not only related to perceived racism, but may interact with other components of the model to influence health status (Clark, 2003a; Dressler, Baleiro, and Dos Santos, 1999; Klag, Whelton, Coresh, Grim, and Kuller, 1991; Knapp et al., 1995). For example, although nil findings have been reported (Krieger et al., 1998), research indicates that darker skin blacks perceive more racism (Keith and Herring, 1991; Klonoff and Landrine, 2000; Udry, Bauman, and Chase, 1971), have lower incomes (Keith and Herring, 1991), are employed in less prestigious positions (Hughes and Hertel, 1990; Keith and Herring, 1991), and have higher diastolic blood pressure (Gleiberman, Harburg, Frone, Russell, and Cooper, 1995) than lighter skin blacks. Whereas the posited mechanisms underlying the relationship of skin tone to socioeconomic and health factors in blacks (e.g., the associations explicated in Figure 14-1) may be different than those in other ethnic groups, it is noteworthy that with some exceptions (Mosley et al., 2000), similar patterns have also been observed in other ethnic groups. In one study of Brazilians, for instance, Telles and Lim (1998) showed that after controlling for human capital and labor market factors, whites earned 26 percent more than “browns” (a racial classification in Brazil), and browns earned 13 percent more than blacks. In another study of 763 white Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, Gleiberman, Harburg, Frone, Russell, and Cooper (1993) found that darker skin tone was associated with higher systolic blood pressure.

Psychological and Physiological Responses

Several responses from different systems are posited to follow perceptions of racism (e.g., psychological and physiological). The psychological responses include anger, helplessness, hopelessness, anxiety, resentment, and fear (Armstead, Lawler, Gorden, Cross, and Gibbons, 1989; Bullock and Houston, 1987; Clark, 2000; Fernando, 1984), and the physiological responses involve the cardiovascular, immune, and neuroendocrine systems (Clark et al., 1999). Whereas cardiac contraction, vasodilation, venoconstriction, vasoconstriction, and decreased excretion of sodium are among the cardiovascular responses, immune response to chronic stress most notably involve cellular and humoral reactions and include lower natural-killer cell activity and suppression of B- and T-lymphocytes, which increase susceptibility to disease (Cohen and Herbert, 1996). Lastly, activation of the pituitary-adrenocortical and hypothalamic-sympathetic-adrenal medullary systems is the primary response of the neuroendocrine system (Burchfield, 1979; Herd, 1991).

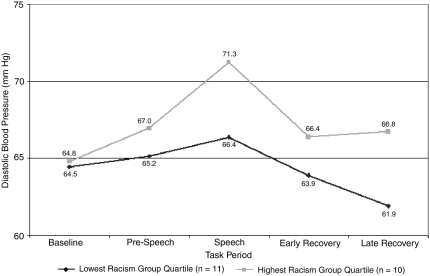

Although published research in this area is lacking (in general) and is nonexistent among the elderly, a limited number of studies using young-and middle-adulthood samples have examined the relationship of perceived racism to resting blood pressure and cardiovascular responses. These studies have shown that perceptions of racism are positively related to stress-induced changes in diastolic blood pressure in blacks (Fang and Myers, 2001; Guyll, Matthews, and Bromberger, 2001). In one study of black females that measured blood pressure responses during a standardized laboratory-speaking task, Clark (2000) found that perceptions of racism (during past year) were related to more exaggerated diastolic blood pressure responses. Even though participants who scored in the upper and lower quartile on perceived racism had similar baseline diastolic blood pressure levels, participants in the upper quartile had higher diastolic blood pressure levels during the prespeech and speech periods, and poorer posttask recovery (Figure 14-3).

Coping Responses

Coping responses and behaviors (coping responses) involve efforts used by or resources available to persons to manage intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli that are perceived as stressful. Although numerous conceptualizations of coping exist (e.g., approach, avoidance, emotion focused, problem focused, and cognitive), these strategies can be characterized as active or passive. Responses that are more active involve efforts to change the nature of the person-environment interaction (e.g., problem solving), whereas more passive responses include efforts to manage “distress” resulting from the perceived stressor (e.g., self-medication) (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). It remains to be determined if individuals use similar coping responses to negotiate stressors (Carver, Scheier, and Weintraub, 1989) or if coping responses are context dependent (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

To the extent that individual differences in psychological and physiological responses to perceived racism are mitigated in part by coping responses (Clark, 2003b; Clark and Adams, in press), these responses are expected to influence allostatic loads in late adulthood. Ethnic minority group members who advance to late adulthood in light of life histories riddled with chronic exposures to racism probably have done so because of the mitigating effects associated with their coping responses and attribution styles. For example, in one probability sample of black adults, LaVeist, Sellars, and Neighbors (2001) found that individuals who are exposed to racism and who attribute these negative experiences to institutional and societal practices—as opposed to personal deficiencies—were more likely to survive the 13-year follow-up period.

Relatively few studies have examined the relationships among perceived racism, coping, and health status. Among the studies that have been conducted, the directions of the relationships have been outcome dependent. For example, in a sample of black college females, Clark and Anderson (2001) found that although some passive and active coping responses were positively related to blood pressure and heart rate responses, both strategies were also inversely related to cardiovascular responses. In a probability sample of black and white adults, Williams et al. (1997a) also found that passive and active coping responses to unfair treatment (including ethnic group discrimination) were positively associated with psychological distress, poorer well-being, and chronic conditions in blacks and whites. In another study exploring the effects of coping with unfair treatment and resting blood pressure, Krieger and Sidney (1996) found that more passive strategies were related to higher resting blood pressure levels in working-class blacks. In yet another study, Noh et al. (1999) found that depression symptoms were higher in Asian refugees who were high in perceived discrimination and high in the use of passive coping strategies, relative to those who were high in perceived discrimination and low in the use of passive coping strategies.

Consistent with Sterling and Eyer (1988) and McEwen (1998), allostasis involves achieving or maintaining physiological systems through change. Although not originally discussed in this way, allostasis could be thought of as the physiological equivalent of coping. For example, if Mr. Leach, a lower SES black male with a dark skin tone in his middle 60s, has come to respond to relatively chronic perceptions of interethnic group and intraethnic racism by briefly removing himself from the environment to “collect himself and regroup,” a coping response that leads to the blunting and elimination of hostile feelings and to a marked reduction in heart rate, he would be said to have coped successfully and to have achieved allostasis. Although possibly adaptive in the short term (e.g., observable decrease in psychological and physiological responses), repeated attempts to maintain psychological and physiological systems in response to chronic perceptions of racism may have associated “costs.” All things equal (e.g., age, socioeconomic resources, occupational status, and education attainment), compare Mr. Leach's psychological and physiological health risk profile to that of a white male peer who has not perceived racism or whose perceptions of racism have been more discrete, or to that of a black male peer who has perceived approximately the same amount of interethnic group racism but has not perceived intraethnic group racism because his skin tone is slightly lighter than a brown paper bag.

Institutional Racism

Even when racism is not perceived, institutional forms of racism may also influence health directly by restricted access to health care or high-quality health care (King, 1996; Kuno and Rothbard, 2002; Sheifer, Escarce, and Schulman, 2000; Whaley, 1998; Williams, 1997). For example, amid some nil findings (Farley et al., 2001; Taylor, Meyer, Morse, and Pearson, 1997), research suggests that ethnic minorities (usually blacks) are less likely than whites to receive select cardiovascular procedures (Gregory, Rhoads, Wilson, O'Dowd, and Kostis, 1999; Johnson, Lee, Cook, Rouan, and Goldman, 1993; Peterson et al., 1997; Schulman et al., 1999; Whittle, Conigliaro, Good, and Lofgren, 1993) and renal procedures (Alexander and Sehgal, 1998; Epstein et al., 2000; Kasiske, London, and Ellison, 1998; McCauley et al., 1997; Soucie, Neylan, and McClellan, 1992). MacLean, Siew, Fowler, and Graham (1987) also found that relative to their elderly French-Canadian, English-Canadian, and Portuguese counterparts, institutional racism contributed to limited or blocked social and health services for Chinese elders in Montreal. Similarly, the contribution of institutional practices to health access problems has been observed among older Mexican Americans (Parra and Espino, 1992). Research indicates that these ethnic group biases (1) begin in medical school (Rathore et al., 2000), (2) are observed among black and white physicians (Chen, Rathore, Radford, Wang, and Krumholz, 2001), and (3) are present in the treatment of patient populations before adulthood (Cuffe, Waller, Cuccaro, Pumariega, and Garrison, 1995).

Allostatic Load and Health Outcomes

The cumulative negative effects associated with the maintenance of psychological and physiological systems are referred to as allostatic load (McEwen and Seeman, 1999). The systems that are involved in the stress response (e.g., psychological, immune, cardiovascular, and neuroendocrine) are the same as those posited to contribute to allostatic load. This load is postulated to increase risk of negative health outcomes. Importantly, these systems do not act in isolation. Rather, they are often related in complex ways (Burchfield, 1985; Cacioppo, 1994; Herd, 1991).

Psychological sequelae include cognitive declines and persisting mood state alterations (Fernando, 1984; McEwen and Seeman, 1999; Seligman, 1975). To the extent that acute perceptions of racism are associated with increased neuroendocrine responses and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter activity, resulting in reduced hippocampal volume, chronic perceptions of racism might be related to cognitive deficits in the later years among those who are disproportionately exposed (McEwen, 2000; Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, and McEwen, 1997). Although the literature is mixed with regard to mental health disparities, research does suggest that perceptions of racism are positively related to mood deficits (Rumbaut, 1994). Ethnic differences in the prevalence of depression in later years could develop secondary to the untoward effects of perceived racism via chronic feelings of uncontrollability, helplessness, and threats to self-esteem (Fernando, 1984).

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes include hypertension, stroke, and heart disease (Burchfield, 1979; Cacioppo, 1994; Clark et al., 1999; Herd, 1991; McEwen and Seeman, 1999). If perceptions of racism are related to acute elevations in vascular reactivity, which over time lead to hyperreactivity, structural changes in the vasculature, and baroreceptor alterations, it is plausible that over the lifespan, chronic perceptions of racism might contribute to the eventual development of hypertension in the later years (Anderson, McNeilly, and Myers, 1991). This cascade of physiological events (namely hyperactivity and exaggerated catecholamine secretions) has also been associated with the progression of arterial plaque formation (Manuck, Kaplan, Adams, and Clarkson, 1995; Manuck, Kaplan, Muldoon, Adams, and Clarkson, 1991), which may place people who are disproportionately exposed to racism at increased risk of developing coronary heart disease.

Although no published studies could be found that have explicitly examined the relationship between perceived racism and immune outcomes, there is no reason to believe that as a stressor, chronic perceptions of racism are associated with different humoral and cellular reactions. The one caveat is that unlike other chronic stressors to which individuals may habituate, it is not known to what extent persons habituate to perceptions of racism. This notwithstanding, the possible cumulative toxic effects from immuno-suppression (e.g., lower natural-killer cell cytotoxic activity, B- and T-lymphocyte suppression, and suppression of the delayed-type hypersensitivity response) include prolonged respiratory infections and increased susceptibility to a myriad of health outcomes (Cohen and Herbert, 1996; Kiecolt-Glaser, Dura, Speicher, Trask, and Glaser, 1991).

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Theory and Assessment

Recent reviews suggest that research investigating the untoward effects of racism is on the rise (Brondolo, Rieppi, Kelly, and Gerin, 2003; Harrell, Hall, and Taliaferro, 2003; Meyer, 2003; Williams, Neighbors, and Jackson, 2003). As the empirical literature exploring associations between racism and health continues to emerge, the development of an equally strong theoretical literature is also needed that explicates the multiple biological, psychological, and social pathways through which perceived racism and institutional racism are posited to influence health outcomes. Concomitantly, special attention should be given to theoretically based assessments of racism that are reliable and valid (Utsey, 1998). Suggestions for future research examining theoretical and assessment issues are delineated below.

- Because perceptions of racism are among the psychosocial stressors that are posited to contribute to health disparities in the later years, assessments of perceived racism should be conducted in the context of a comprehensive evaluation of psychosocial stressors (e.g., those that might be culture specific). Although perceptions of interethnic group racism and intraethnic group racism are important considerations, the extent to which racism interacts with acculturation to influence the psychological and physiological risk profiles of black elders would probably lead to a more informed understanding of the complex interplay between racism and cultural factors. For example, consistent with the research of Landrine and Klonoff (1996), black elders may report fewer perceptions compared to their less seasoned counterparts because they are more acculturated. To assess racism in isolation of the other powerful psychosocial predictors of physiological activity would likely limit the potential to more fully explain ethnic group health disparities in the later years. Also, conceptual differences notwithstanding (e.g., researchers who assert that blacks lack the social and economic “power” to be racist but can discriminate against members of the in-group versus researchers who contend that intraethnic group racism involves the perpetuation of racism among in-group members), further research is needed that explores the additive and interactive relationships of interethnic group and intraethnic group racism to psychological and physiological functioning, which might further elucidate the mechanisms that contribute to within-group and between-group disparities in health during the later years.

- Although research suggests that perceptions of events as stressful are more predictive of psychological and physiological functioning than objective demands, comparative research exploring the relationship between a person's perceptions and objective demands might provide additional concurrent validity. Further research is also needed to be able to more clearly interpret observed findings with respect to perceived racism. For example, some persons who perceive stimuli as involving racism probably do so because it is less anxiety provoking than attributing the failure of being promoted at work to personal deficits. Furthermore, some persons who do not report perceiving racism probably fail to do so because of denial or as an attempt to avoid the expected psychological distress that would be associated with negotiating an uncontrollable stressor. Accordingly, in addition to assessing perceptions of racism, the simultaneous measurement of other contributory factors such as attribution style, impression management, self-deception, and affective state would help to delineate the possible mitigating effects of these variables.

- According to Krieger (1999), of the 20 published studies that have assessed the effects of unfair treatment (including racism), more than half used measures with questionable or unreported psychometric properties. When psychometric data were presented, little to no attention was devoted to the generalizability of these data for the gender and/or ethnic groups being studied. Additionally, almost without exception, each author used different measures or response formats to assess racism. As a result of these methodological caveats, comparisons of findings across studies remain somewhat limited. Measures used to assess racism should (1) be reliable and valid for the target groups and subgroups (e.g., native-born Hispanics and immigrant Hispanics) as well as ethnic-gender groups and subgroups (e.g., Filipino males and Filipino females) being studied, (2) be specific enough to capture the reported multidimensional nature of racism, and (3) be developed with equivalent shorter and longer versions to facilitate use with different study designs.

- Systematic efforts by national agencies to “unpack” the broad ethnic groupings are needed. In addition to unpacking such broad ethnic grouping as Asians, Hispanics, and Pacific Islanders, ethnic groups who are presumed to be more or less homogeneous (e.g., blacks and whites) should also be unpacked to provide a more informed understanding of the cumulative perceptions of racism by ethnic subgroups. For example, although viewing whites as a homogeneous group probably has been convenient, the health profiles of white ethnic groups (e.g., Irish, Turks, and Cypriots) probably are influenced by differences in the amount of discrimination to which these ethnic groups are exposed and perceived (Aspinall, 1998).

Research Design

Given the dearth of data exploring the relationship between perceived racism and other components of the model proposed herein, studies using different research designs are warranted. These research designs should take the multidimensional nature of racism into consideration (Harrell, 2000), as well as the different levels (e.g., individual, cultural, and institutional) at which racism is perpetuated (Jones, 1997). In the section that follows, suggestions for future research using different designs are presented.

- National and large-scale studies exploring perceptions of interethnic group and intraethnic group racism within and between ethnic groups across the lifespan would provide the necessary baseline information, as well as identify groups who may be at increased risk. If allostatic load results from the cumulative effects of efforts to maintain psychological and physiological systems, the assessment of perceived racism in these studies (e.g., longitudinal) should begin prior to the later years and include cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Because of the often cited monetary limitations of funding numerous longitudinal studies and the time involved in the collection of longitudinal data, cross-sectional and shorter term prospective studies are essential and may provide the necessary data for more targeted longitudinal research. For example, if cross-sectional research indicates that the perceptual base rates of racism (peak in middle adulthood and presumably the allostatic burden associated with these perceptions), targeted longitudinal research could be initiated during this period to explore concomitant changes in psychological and physiological systems.

- Studies exploring the relationship of perceived racism to the cascade of shorter term (e.g., psychological and physiological stress responses) and longer term (e.g., hippocampal volume, depression, cognitive declines, arterial elasticity) processes posited to contribute to allostatic load are needed, as well as integrated/multilevel research that examines how perceived racism interacts with psychological factors (e.g., coping efficacy), behavioral risk factors (e.g., smoking and alcohol consumption), and constitutional factors (e.g., genetic predisposition) to influence allostatic burden and health status. For example, among persons high in perceived racism, are different types of coping (e.g., problem focused and emotion focused) related to arterial elasticity and blood pressure reactivity, and, if so, are racism-specific coping strategies reflective of styles used to deal with other stressors (consistent with a trait approach)? Does the efficacy of a given racism coping strategy depend on the context in which it is perceived (e.g., work versus public realm), the ethnicity of the perpetrator (i.e., interethnic group or intraethnic group), or the position of the perpetrator (e.g., supervisor or subordinate)? These types of inquiries are essential to understanding how perceived racism “gets under the skin” and concomitantly contributes to psychological and physiological vulnerabilities in more seasoned adults.

- Given the history of de jure and de facto racism in the United States, more systematic studies exploring the extent to which these forms of racism continue to influence health status directly (e.g., access to services) and indirectly (e.g., nonequivalent returns on education, residential segregation, median household income, and educational attainment) are needed. For example, the observation that black males and white males differ with respect to returns on education is often cited as an example of interethnic group racism. Given the rather crude and descriptive nature of these data, however, a number of alternate hypotheses could be forwarded to explain these differences and should be explored to examine the robustness of these findings. For example, given a larger proportion of bachelor's degrees earned by blacks are in the liberal arts relative to the proportion of those earned by whites in the liberal arts, it is conceivable that the observed income differences are secondary to career-specific income differences. A stronger argument for the persistence of racism could be made if, for example, black males and white males with doctorates in psychology from Wayne State University, who currently work in the private sector of Detroit as consultants, earn different incomes.

The exploration of alternate hypotheses would also be important when interpreting data on ethnic group disparities in receiving medical treatments. For example, to the extent that atypical symptom presentations are associated with lower intervention rates (Summers, Cooper, Woodward, and Finerty, 2001), it could be argued that secondary to culturally sanctioned differences in symptom presentations, older members of ethnic minority groups do not present in ways that would lead to standard medical treatments. A cautionary note is in order, however, if in fact typical symptom presentations or standard assessment procedures are based or normed primarily on nonethnic minority group members and used to determine treatment options for ethnic minority elders. For example, Miles (2001) advised against the use of standard screening tools to assess cognitive functioning in elderly blacks. She reasoned that because cognitive functioning determines the course of various treatments for older adults, and black elders more than any other age cohort have been systematically deprived of access to quality education, the continued use of standard cognitive batteries, which are more likely to incorrectly label those whose education level does not exceed the seventh grade as being mildly demented, would perpetuate the untoward effects of institutional racism.

- In addition to studies examining interethnic group differences, coordinated federal efforts are needed to advocate for the importance of intraethnic group investigations. These efforts would help to serve at least two purposes. First, they might help to dismantle the erroneous belief, but widely accepted practice of many federal grant reviewers and journal editors, that “acceptable” research designs must include a white comparison group. Second, although it is important to decrease interethnic group disparities in the later years, it seems as if it would be equally important to decrease the prevalence of (dis)ease—regardless of interethnic group disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants (1R03 MH56868 and 1 K01 MH01867) to the author from the National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- Adams JP, Dressler WW. Perceptions of injustice in a black community: Dimensions and variations. Human Relations. 1988;41:753–767.

- Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1148–1152. [PubMed: 9777814]

- American Anthropological Association. Statement on race. American Anthropologist. 1998;100:712–713.

- Anderson NB, Armstead CA. Toward understanding the association of socioeconomic status and health: A new challenge for the biopsychosocial approach. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57:213–225. [PubMed: 7652122]

- Anderson NB, McNeilly M, Myers H. Autonomic reactivity and hypertension in blacks: A review and proposed model. Ethnicity and Disease. 1991;1:154–170. [PubMed: 1842532]

- Armstead CA, Lawler KA, Gorden G, Cross J, Gibbons J. Relationship of racial stressors to blood pressure responses and anger expression in black college students. Health Psychology. 1989;8:541–556. [PubMed: 2630293]

- Aroian KJ, Norris AE, Patsdaughter CA, Tran TV. Predicting psychological distress among former Soviet immigrants. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1998;44:284–294. [PubMed: 10459512]

- Aspinall PJ. Describing the “white” ethnic group and its composition in medical research. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1797–1808. [PubMed: 9877349]

- Barnett E, Casper ML, Halverson JA, Elmes GA, Braham VE, Majeed ZA, Bloom AS, Stanley S. Men and heart disease: An atlas of racial and ethnic disparities in mortality. 1st ed. Morgantown: West Virginia University; 2001. Office for Social Environment and Health Research.

- Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:554–563. [PubMed: 11572421]

- Bledsoe T, Combs M, Sigelman L, Welch S. Trends in racial attitudes in Detroit, 1968-1992. Urban Affairs Review. 1996;31:508–528.

- Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Kelly KP, Gerin W. Perceived racism and blood pressure: A review of the literature and conceptual and methodological critique. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25:55–65. [PubMed: 12581937]

- Bullock SC, Houston E. Perceptions of racism by black medical students attending white medical schools. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1987;79:601–608. [PMC free article: PMC2625534] [PubMed: 3612829]

- Burchfield SR. The stress response: A new perspective. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41:661–672. [PubMed: 397498]

- Burchfield SR. Stress: An integrative framework. In: Burchfield SR, editor. Stress: Psychological and physiological interactions. New York: Hemisphere; 1985. pp. 381–394.

- Cacioppo J. Social neuroscience. Autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune responses to stress. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:113–128. [PubMed: 8153248]

- Carver DP, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. [PubMed: 2926629]

- Casper ML, Barnett E, Halverson JA, Elmes GA, Braham VE, Majeed ZA, Bloom AS, Stanley S. Morgantown: West Virginia University; 2000. Women and heart disease: An atlas of racial and ethnic disparities in mortality. Office for Social Environment and Health Research.

- Charatz-Litt C. A chronicle of racism: The effects of the white medical community on black health. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1992;84:717–725. [PMC free article: PMC2571643] [PubMed: 1507263]

- Chen J, Rathore SS, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Racial differences in the use of cardiac catheterization after acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1443–1449. [PubMed: 11346810]

- Clark R. Perceptions of interethnic group racism predict increased blood pressure responses to a laboratory challenge in college women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22:214–222. [PubMed: 11126466]

- Clark R. Parental history of hypertension and coping responses predict blood pressure changes to a perceived racism speaking task in black college volunteers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003a;65:1012–1019. [PubMed: 14645780]

- Clark R. Self-reported racism and social support predict blood pressure reactivity in blacks. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003b;25:127–136. [PubMed: 12704015]

- Clark R. Inter-ethnic group and intra-ethnic racism: Perceptions and coping in Black university students. Journal of Black Psychology. in press.

- Clark R, Adams JH. Moderating effects of perceived racism on John Henryism and blood pressure reactivity in Black college females. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. in press. [PubMed: 15454360]

- Clark R, Anderson NB. Efficacy of racism-specific coping styles as predictors of cardiovascular functioning. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:286–295. [PubMed: 11456003]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. [PubMed: 10540593]

- Cohen S, Herbert TB. Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:113–142. [PubMed: 8624135]

- Collier J, Burke A. Racial and sexual discrimination in the selection of students for London medical schools. Medical Education. 1986;20:86–90. [PubMed: 3959932]

- Cooper RS. Health and the social status of blacks in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3:137–144. [PubMed: 8269065]

- Cooper RS. Social inequality, ethnicity and cardiovascular disease. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:S48–S52. [PubMed: 11759851]

- Cuffe SP, Waller JL, Cuccaro ML, Pumariega AJ, Garrison CZ. Race and gender differences in the treatment of psychiatric disorders in young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1536–1543. [PubMed: 8543522]

- Dressler WW, Baleiro MC, Dos Santos JE. Culture, skin color, and arterial blood pressure in Brazil. American Journal of Human Biology. 1999;11:49–59. [PubMed: 11533933]

- Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, David-Kasdan JA, Carlson D, Fuller J, Marsh D, Conti RM. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:1537–1544. [PMC free article: PMC4598055] [PubMed: 11087884]

- Essed P. Everyday racism. Claremont, CA: Hunter House; 1991.

- Fang CY, Myers HF. The effects of racial stressors and hostility on cardiovascular reactivity in African American and Caucasian men. Health Psychology. 2001;20:64–70. [PubMed: 11199067]

- Farley JH, Hines JF, Taylor RR, Carlson JW, Parker MF, Kost ER, Rogers SJ, Harrison TA, Macri CI, Parham GP. Equal care ensures equal survival for African-American women with cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:869–873. [PubMed: 11241257]

- Ferguson JA, Weinberger M, Westmoreland GR, Mamlin LA, Segar DS, Greene JY, Martin DK, Tierney WM. Racial disparity in cardiac decision making: Results from patient focus groups. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1450–1453. [PubMed: 9665355]

- Fernando S. Racism as a cause of depression. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1984;30:41–49. [PubMed: 6706494]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed: 11011506]

- Forman TA, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Race, place, and discrimination. Social Problems. 1997;9:231–261.

- Gary L. African American men's perceptions of racial discrimination: A sociocultural analysis. Social Work Research. 1995;19:207–217.

- Gatewood WB Jr. Aristocrats of color: South and North, the black elite, 1880-1920. Journal of Southern History. 1988;54:3–20.

- Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:615–623. [PMC free article: PMC1447127] [PubMed: 11919062]

- Gilvarry CM, Walsh E, Samele C, Hutchinson G, Mallet R, Rabe-Hesketh S, Fahy T, van Os J, Murray RM. Life events, ethnicity and perceptions of discrimination in patients with severe mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1999;34:600–608. [PubMed: 10651179]

- Gleiberman L, Harburg E, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Skin color, ancestry, and blood pressure among whites in Erie County, New York. Ethnicity and Disease. 1993;3:378–386. [PubMed: 7888989]

- Gleiberman L, Harburg E, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Skin colour, measures of socioeconomic status, and blood pressure among blacks in Erie County, NY. Annals of Human Biology. 1995;22:69–73. [PubMed: 7762977]

- Gregory PM, Rhoads GC, Wilson AC, O'Dowd KJ, Kostis JB. Impact of availability of hospital-based invasive cardiac services on racial differences in the use of these services. American Heart Journal. 1999;138:507–517. [PubMed: 10467202]

- Guyll M, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT. Discrimination and unfair treatment: Relationship to cardiovascular reactivity among African American and European American women. Health Psychology. 2001;20:315–325. [PubMed: 11570645]

- Hall DE. Bias among African-Americans regarding skin color: Implications for social work practice. Research on Social Work Practice. 1992;2:479–486.

- Harrell JP, Hall S, Taliaferro J. Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: An assessment of the evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:243–248. [PMC free article: PMC1447724] [PubMed: 12554577]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. [PubMed: 10702849]

- Herd JA. Physiological Reviews. Vol. 71. 1991. Cardiovascular responses to stress; pp. 305–330. [PubMed: 1986391]

- Hughes M, Hertel BR. The significance of color remains: A study of life chances, mate selection, and ethnic consciousness among black Americans. Social Forces. 1990;68:1105–1120.

- Jackson SA, Anderson RT, Johnson NJ, Sorlie PD. The relation of residential segregation to all cause mortality: A study in black and white. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:615–617. [PMC free article: PMC1446199] [PubMed: 10754978]

- James SA. Racial and ethnic differences in infant mortality and low birthweight: A psychosocial critique. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3:130–136. [PubMed: 8269064]

- Johnson PA, Lee TH, Cook EF, Rouan GW, Goldman L. Effect of race on the presentation and management of patients with acute chest pain. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;118:593–601. [PubMed: 8452325]

- Jones JM. Prejudice and racism. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1972.

- Jones JM. Prejudice and racism. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

- Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:624–631. [PMC free article: PMC1447128] [PubMed: 11919063]

- Kasiske BL, London W, Ellison MD. Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1998;9:2142–2147. [PubMed: 9808103]

- Kaufman JS, Long AE, Liao Y, Cooper RS, McGee DL. The relationship between income and mortality in U.S. blacks and whites. Epidemiology. 1998;9:147–155. [PubMed: 9504282]

- Keith VM, Herring C. Skin tone and stratification in the black community. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97:760–778.

- Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Lochner K, Jones C, Prothrow-Stith D. (Dis)respect and black mortality. Ethnicity and Disease. 1997;7:207–214. [PubMed: 9467703]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed: 10513145]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Dura JR, Speicher CE, Trask OJ, Glaser R. Spousal caregivers of dementia victims: Longitudinal changes in immunity and health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53:345–362. [PubMed: 1656478]

- King G. Institutional racism and the medical/health complex: A conceptual analysis. Ethnicity and Disease. 1996;6:30–46. [PubMed: 8882834]

- Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Coresh J, Grim CE, Kuller LH. The association of skin color with blood pressure in U.S. blacks with low socioeconomic status. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265:599–602. [PubMed: 1987409]

- Klassen AC, Hall AG, Saksvig B, Curbow B, Klassen DK. Relationship between patients' perceptions of disadvantage and discrimination and listing for kidney transplantation. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:811–817. [PMC free article: PMC1447166] [PubMed: 11988452]

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H. Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;23:329–338. [PubMed: 10984862]

- Knapp RG, Keil JE, Sutherland SE, Rust PF, Hames C, Tyroler HA. Skin color and cancer mortality among black men in the Charleston Heart Study. Clinical Genetics. 1995;47:200–206. [PubMed: 7628122]

- Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Social Science Medicine. 1990;12:1273–1281. [PubMed: 2367873]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services. 1999;29:295–352. [PubMed: 10379455]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. [PMC free article: PMC1380646] [PubMed: 8876504]

- Krieger N, Rowley DL, Herman AA, Avery B, Phillips MT. Racism, sexism, and social class: Implications for studies of health, disease, and well-being. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9:82–122. [PubMed: 8123288]

- Krieger N, Sidney S, Coakley E. Racial discrimination and skin color in the CARDIA study: Implications for public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1308–1313. [PMC free article: PMC1509091] [PubMed: 9736868]

- Kuno E, Rothbard AB. Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:567–572. [PubMed: 11925294]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168.

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Racial discrimination and cigarette smoking among blacks: Findings from two studies. Ethnicity and Disease. 2000;10:195–202. [PubMed: 10892825]

- LaVeist TA, Sellars R, Neighbors HW. Perceived racism and self and system blame attribution: Consequences for longevity. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:711–721. [PubMed: 11763865]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

- Lewontin R. Human diversity. New York: Scientific American Books; 1995.

- Lieberman L, Jackson FL. Race and three models of human origin. American Anthropologist. 1995;97:231–242.

- Loo CM, Fairbank JA, Scurfield RM, Ruch LO, King DW, Adams LJ, Chemtob CM. Measuring exposure to racism: Development and validation of a Race-Related Stress Scale (RRSS) for Asian American Vietnam veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:503–520. [PubMed: 11793894]

- Lowe M, Kerridge IH, Mitchell KR. “These sorts of people don't do very well”: Race and allocation of health care resources. Journal of Medical Ethics. 1995;21:356–360. [PMC free article: PMC1376833] [PubMed: 8778460]

- Lowell BL, Teachman J, Jing Z. Unintended consequences of immigration reform: Discrimination and Hispanic employment. Demography. 1995;32:617–628. [PubMed: 8925950]

- MacLean MJ, Siew N, Fowler D, Graham I. Institutional racism in old age: Theoretical perspectives and a case study about access to social services [Special issue] Canadian Journal on Aging. 1987;6:128–140.

- Manuck SB, Kaplan JR, Muldoon MF, Adams MR, Clarkson TB. The behavioral exacerbation of atherosclerosis and its inhibition by propranolol. In: McCabe PM, Schneiderman N, Field TM, Skyler JS, editors. Stress, coping and disease. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 51–72.

- Manuck SB, Kaplan JR, Adams MR, Clarkson TB. Studies of psychosocial influences on coronary artery atherosclerosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Health Psychology. 1995;7:113–124. [PubMed: 3371304]

- Marmot MG, Kogevinas M, Elston MA. Social/economic status and disease. Annual Review of Public Health. 1987;8:111–135. [PubMed: 3555518]

- McBean AM, Gornick M. Differences by race in the rates of procedures performed in hospitals for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financing Review. 1994;15:77–90. [PMC free article: PMC4193437] [PubMed: 10172157]

- McCauley J, Irish W, Thompson L, Stevenson J, Lockett R, Bussard R, Washington M. Factors determining the rate of referral, transplantation, and survival on dialysis in women with ESRD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1997;30:739–748. [PubMed: 9398116]

- McConahay JB, Hough JC. Symbolic racism. Journal of Social Issues. 1976;32:23–45.

- McDonald R, Vechi C, Bowman J, Sanson-Fisher R. Mental health status of a Latin American community in New South Wales. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;30:457–462. [PubMed: 8887694]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:171–179. [PubMed: 9428819]

- McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: From serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Research. 2000;886:172–189. [PubMed: 11119695]

- McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:30–47. [PubMed: 10681886]

- McKeigue PM, Richards JD, Richards P. Effects of discrimination by sex and race on the early careers of British medical graduates during 1981-1987. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:961–964. [PMC free article: PMC1664175] [PubMed: 2249025]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:262–265. [PMC free article: PMC1447727] [PubMed: 12554580]

- Miles TP. Dementia, race, and education: A cautionary note for clinicians and researchers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:490. [PubMed: 11347798]

- Mosley JD, Appel LJ, Ashour Z, Coresh J, Whelton PK, Ibrahim MM. Relationship between skin color and blood pressure in Egyptian adults: Results from the National Hypertension Project. Hypertension. 2000;36:296–302. [PubMed: 10948093]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 1998 with socioeconomic status and health chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: Author; 1998.

- Neal AM, Wilson ML. The role of skin color and features in the black community: Implications for black women and therapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 1989;9:323–333.

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Discrimination and emotional well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed: 10513144]

- Okazawa-Rey M, Robinson T, Ward JV. Black women and the politics of skin color and hair. Women's Studies Quarterly. 1986;14:13–14.

- Outlaw FH. Stress and coping: The influence of racism on the cognitive appraisal processing of African Americans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1993;14:399–409. [PubMed: 8244690]

- Pak AW, Dion KL, Dion KK. Social-psychological correlates of experienced discrimination: Test of the double jeopardy hypothesis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1991;15:243–254.

- Pamuk E, Makuc D, Heck K, Reuben C, Lochner K. Socioeconomic status and health chartbook: Health, United States, 1998. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998.

- Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity and mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:103–109. [PubMed: 8510686]

- Parra EO, Espino DV. Barriers to health care access faced by elderly Mexican Americans [Special issue] Clinical Gerontologist. 1992;11:171–177.

- Pernice R, Brook J. Refugees and immigrants' mental health: Association of demographic and post-migration factors. Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;136:511–519. [PubMed: 8855381]

- Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:480–486. [PubMed: 9017942]

- Polednak AP. Segregation, discrimination and mortality in U.S. blacks. Ethnicity and Disease. 1996;6:99–108. [PubMed: 8882839]

- Rathore SS, Lenert LA, Weinfurt KP, Tinoco A, Taleghani CK, Harless W, Schulman KA. The effects of patient sex and race on medical students' ratings of quality of life. American Journal of Medicine. 2000;108:561–566. [PubMed: 10806285]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794.

- Sakamoto A, Wu HH, Tzeng JM. The declining significance of race among American men during the latter half of the twentieth century. Demography. 2000;37:41–51. [PubMed: 10748988]

- Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dube R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Escarce JJ. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:618–626. [PubMed: 10029647]

- Schuman H, Hatchett S. Black racial attitudes. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 1974.

- Sears DO. Symbolic racism. In: Katz PA, Taylor DA, editors. Eliminating racism: Profiles in controversy. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 53–84.

- Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of adaptation-allostatic load and its health consequences: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:2259–2268. [PubMed: 9343003]

- Seligman MEP. Helplessness: On depression, development and death. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman; 1975.

- Sheifer SE, Escarce JJ, Schulman KA. Race and sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal. 2000;139:848–857. [PubMed: 10783219]

- Sigelman L, Welch S. Black Americans' views of racial inequality: The dream deferred. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Smith DG, Shipley R, Rose G. Magnitude and causes of socioeconomic differentials in mortality: Further evidence from the Whitehall Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1990;44:265–270. [PMC free article: PMC1060667] [PubMed: 2277246]

- Soucie JM, Neylan JF, McClellan W. Race and sex differences in the identification of candidates for renal transplantation. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1992;19:414–419. [PubMed: 1585927]

- Sterling P, Eyer J. Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In: Fisher S, Reason J, editors. Handbook of life stress, cognition and health. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. pp. 629–649.

- Summers RL, Cooper GJ, Woodward LH, Finerty L. Association of atypical chest pain presentations by African Americans and the lack of utilization of reperfusion therapy. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:463–468. [PubMed: 11572413]

- Tang Z, Trovato R. Discrimination and Chinese fertility in Canada. Social Biology. 1998;45:172–193. [PubMed: 10085733]

- Taylor AJ, Meyer GS, Morse R, Pearson CS. Can characteristics of a health care system mitigate ethnic bias in access to cardiovascular procedures? Experience from the Military Health Services System. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;30:901–907. [PubMed: 9316516]

- Telles EE, Lim N. Does it matter who answers the race question? Racial classification and income inequality in Brazil. Demography. 1998;35:465–474. [PubMed: 9850470]

- Tennstedt S, Chang BH. The relative contribution of ethnicity versus socioeconomic status in explaining differences in disability and receipt of informal care. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53:61–70. [PubMed: 9520931]

- Udry JR, Bauman KE, Chase C. Skin color, status, and mate selection. American Journal of Sociology. 1971;76:722–733.

- Utsey SO. Assessing the stressful effects of racism: A review of instrumentation. Journal of Black Psychology. 1998;24:269–288.

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG. Development and validation of the Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS). Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43:490–501.

- Utsey SO, Payne YA, Jackson ES, Jones AM. Race-related stress, quality of life indicators, and life satisfaction among elderly African Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:224–233. [PubMed: 12143100]

- Villarruel AM, Canales M, Torres S. Bridges and barriers: Educational mobility of Hispanic nurses. Journal of Nursing Education. 2001;40:245–251. [PubMed: 11554458]

- West P. Health inequalities in the early years: Is there equalisation in youth? Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:833–858. [PubMed: 9080566]

- Whaley AL. Racism in the provision of mental health services: A social-cognitive analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:47–57. [PubMed: 9494641]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, Stubben JD. Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:405–424. [PubMed: 11831140]

- Whitfield K, Weidner G, Clark R, Anderson NB. Sociodemographic diversity in behavioral medicine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:463–481. [PubMed: 12090363]

- Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, Lofgren RP. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs medical system. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:621–627. [PubMed: 8341338]

- Williams DR. Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;7:322–333. [PubMed: 9250627]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Socioeconomic and racial differences in health. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386.

- Williams DR, Neighbors H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: Evidence and needed research. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:800–816. [PubMed: 11763305]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J. The costs of racism: Discrimination, race, and health; Paper presented at the joint meeting of the Public Health Conference on Records and Statistics and Data User's Conference; Washington, DC. Jul, 1997a.

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997b;2:335–351. [PubMed: 22013026]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. [PMC free article: PMC1447717] [PubMed: 12554570]

- Yetman N. Introduction: Definitions and perspectives. In: Yetman N, editor. Majority and minority: The dynamics of race and ethnicity in American life. 4th. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1985. pp. 1–20.

Figures

FIGURE 14-2

Reports of everyday discrimination as a function of ethnicity and age.

SOURCE: Forman et al. (1997).

FIGURE 14-3

Absolute diastolic blood pressure levels for participants scoring in the upper and lower quartiles on perceived racism measure.

SOURCE: Clark (2000).