Abbreviations

- AMSTAR

A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

- CADTH

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CRD

Centre for Reviews and dissemination

- ICER

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- NRT

Nicotine replacement therapy

- QALY

Quality adjusted life-year

- RR

Relative risk

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SR

Systematic review

- UK

United Kingdom

- US

United States

Context and Policy Issues

The use of tobacco is known to be one of the most preventable causes of morbidity and mortality and it has been a challenging concern for health systems.1 Pharmacological therapy has been identified as being an effective approach for tobacco smoking cessation; however, non-pharmacological therapy has also been suggested to be useful in assisting patients who are ready to quit.2 The management of smoking cessation has often been identified as an opportunity for pharmacists.1 Community pharmacists are in frequent contact with patients and are already well positioned to respond to immediate patient needs.1

It is recognized that tobacco is intertwined in the culture of Indigenous peoples resulting in higher smoking rates and higher disease burden compared to non-Indigenous populations.3 Therefore, it is crucial to identify any evidence-based approaches that can effectively reduce this gap by improving health equity.3 It is important to consider cultural differences when developing interventions for this particular population. Considering cultural factors and sensitivities, it is crucial to identify clinically effective and cost-effective interventions for smoking cessation in different subpopulations.

In addition to population considerations, various jurisdictions have provided financial support for pharmacists to offer smoking cessation interventions, including counselling and offering pharmacological therapies, across Canada, but jurisdictions vary greatly in the implementation of these programs.4 Some jurisdictions have implemented pilot projects and evidence regarding the clinical and cost-effectiveness of these programs is emerging.4

The purpose of this report is to review the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of pharmacist-led tobacco smoking cessation interventions?

What is the cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led tobacco smoking cessation interventions versus self-directed smoking cessation interventions?

Key Findings

Three systematic reviews were identified regarding the clinical effectiveness of pharmacist-led interventions for tobacco smoking cessation. One systematic review was identified on the cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions. The overall quality of evidence was low, and high heterogeneity existed between the included studies, making it difficult to determine the overall effectiveness of these interventions.

Very low- to moderate-quality evidence from three systematic reviews suggested that pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions may lead to higher rates or no difference in rates of smoking cessation, as compared to usual care or no intervention, although there was a high degree of uncertainty in these findings. No other clinical effectiveness outcomes, including adverse events, were reported.

Evidence of unknown quality from one very low-quality systematic review suggested that pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions were cost-effective in Europe.

Given the limited availability and low quality of evidence, the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation remain uncertain.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, the websites of Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concept was pharmacist-led tobacco smoking cessation interventions. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2014 and July 29, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, already captured in an included systematic review, or were published prior to 2014. Primary studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies, were excluded if the population was non-Indigenous.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic reviews (SRs) were critically appraised using the AMSTAR 2 tool.5 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

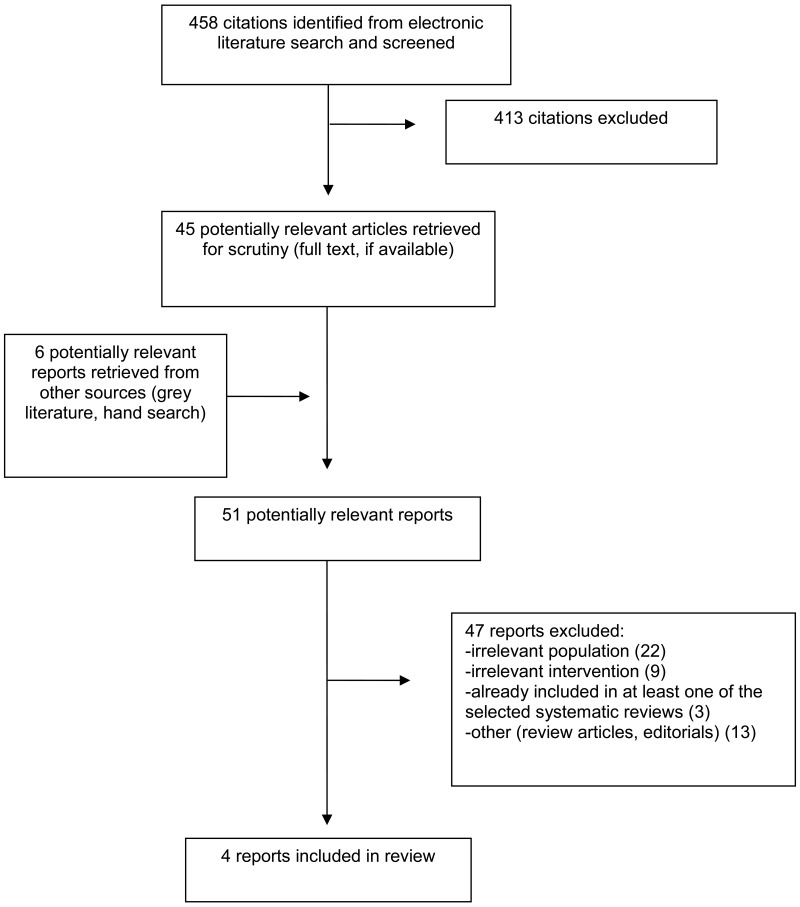

A total of 458 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 413 citations were excluded and 45 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Six potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full-text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 47 publications were excluded for various reasons, and four publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised four SRs. Of the excluded studies, one was an overview of reviews6 that met the inclusion criteria for this report; however, only one of the included SRs was relevant to this report, and because it was captured by the search and contained more comprehensive information, the SR7 was retained directly and the overview was excluded. Two other SRs,8,9 met the inclusion criteria but were excluded for having overlapping primary studies with more comprehensive SRs included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA10 flowchart of the study selection. Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 6.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Four eligible SRs were identified, with one published in 2019,11 two published in 2016,12,13 and one published in 2014.7 The overlap of primary studies that are relevant to this report between the SRs can be found in Appendix 5. Two of the SRs specifically included studies from the literature for smoking cessation interventions led by pharmacists7,11 while two SRs included studies for public health interventions more broadly, including smoking cessation interventions led by pharmacists.12,13 Two SRs combined the studies in a meta-analysis,7,12 however, in one SR12 the meta-analysis included primary studies that were not relevant to this report and the results of the meta-analysis have not been included in this report. Between all of the identified SRs, search strategies included studies up to April 2019.7,11–13 One SR only included cost-effectiveness studies (some of which reported on clinical effectiveness outcomes)13 while the other three SRs included RCTs, non-randomized interventions, and observational studies on the clinical effectiveness of pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions.7,11,12

Country of Origin

One systematic review was conducted by authors in the United States,11 one was from authors in the United Kingdom,12 one was from authors in Switzerland,13 and one was from authors in Australia.7

Patient Population

All four SRs specified that the participants had be smokers7,11,13 or enrolled in a smoking cessation intervention from a community pharmacy.12 The SR by O’Reilly et al. considered studies that included adult patients who used tobacco products from the United States.11 The review by Perraudin et al. considered studies that included European patients who smoked.13 Brown et al. included patients who received a smoking cessation intervention from a community pharmacy and included in the studies were adult patients from the UK, US, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Japan, and Denmark in the community setting.12 The SR by Saba et al. included patients who were smokers from studies conducted in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sweden.7

Interventions and Comparators

All four SRs considered pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation, which varied considerably in design across the primary studies.7,11–13 Pharmacist-led interventions included one-on-one counseling, group sessions, tailored approaches, counseling that incorporated the “stage of change” model, behavioural support, and financial incentives. In some cases, the pharmacist-led intervention was provided with nicotine replacement therapy. The interventions varied in length (e.g., one to four months), and in number of visits with a pharmacist (e.g., single visits versus multiple visits). The SRs did not necessarily require a comparator but the most of the included studies did have comparators which included usual care or other active interventions from a pharmacy, which may have included pharmacological therapy.7,11–13

Outcomes

In the systematic review by O’Reilly et al, studies were included in the review if tobacco cessation was reported as a primary or secondary outcome.11 The systematic review by Brown et al., indicated that the primary outcome of the relevant studies was quit rate.12 The SR by Saba et al. reported on smoking abstinence, reported as continuous abstinence or point prevalence.7 The SR of economic evaluations reported on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER).13

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 3.

Systematic Reviews

The AMSTAR 25 assessment of the four SRs7,11–13 found that three SRs7,11,12 had well described research questions and inclusion criteria, while one of these SRs12 had a protocol that was registered and published. The SR of cost-effectiveness studies13 lacked detail in the research question and inclusion criteria, and did not have an a priori protocol. All four SRs included both RCTs and non-randomized studies.

All four SRs7,11–13 conducted a comprehensive search of relevant databases and conducted study selection in duplicate, and one SR also searched the grey literature.12 Data extraction was performed in duplicate in three SRs7,12,13 but it was unclear how many people performed the data extraction in the other SR.11 None of the SRs provided a list of the excluded studies, but they all reported the number of excluded full texts as well as the reasons for exclusion.

One of the SRs12 provided a detailed summary of the included primary studies, including additional details in an online supplement. This was important for determining whether the evidence in the SR met the inclusion criteria for this report. In the other three SRs details were lacking in descriptions of the populations,7,11,13 interventions,13 comparators,7,11,13 and outcomes,13 thus reducing the certainty that these primary studies met the inclusion criteria for this report. With regards to the participants, two SRS7,12 included details about the number of cigarettes smoked per day by the participants, one SR described the participants as smokers but did not provide other details,13 and one SR did not describe the participants included in the primary studies.11 None of the SRs provided information on the length of time participants had been smokers.7,11–13

Two SRs7,12 used satisfactory techniques to assess the risk of bias or quality of the studies, and one SR7 considered the potential impact of the risk of bias in the individual studies when discussing the results of the review. One SR11 did not conduct a formal risk of bias assessment but reported that the overall quality of the evidence was considered to be low based on the majority of the studies (14 or 16) having a non-randomized study design. The SR of cost-effectiveness studies13 did not assess risk of bias.

One SR7 conducted a meta-analysis of the included studies that was relevant to this report. The primary analysis in this SR had moderate statistical heterogeneity and the authors may have inappropriately combined study types by combining RCTs with non-randomized studies in this analysis. The authors did conduct a subgroup analysis by study design, which demonstrated a difference in effectiveness by study design, but did not reduce statistical heterogeneity. The authors also conducted a subgroup analysis to examine the impact of risk of bias on the results, which resulted in a stronger effect estimate and less statistical heterogeneity in the low risk of bias group. The authors of this SR also discussed the potential impact of other sources of heterogeneity such as the type of interventions, the length of follow-up, and the outcome assessment methods. One other SR12 included a meta-analysis, however it included primary studies that were not relevant to this CADTH report and thus the results of the meta-analysis were not extracted and the meta-analysis was not critically appraised.

One SR12 reported the sources of funding of the primary studies, and the other SRs did not. The review authors declared no conflicts of interest in all four SRs.7,11–13

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents a table of the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Clinical Effectiveness of Pharmacist-Led Interventions of Smoking Cessation

Smoking Cessation

Three SRs7,11,12 reported evidence on the effects of pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation. There was minimal overlap of primary studies across these SRs (Appendix 5), with one primary study included in all three SRs, and two other primary studies captured in two of the SRs. Smoking cessation was reported in different ways across the systematic reviews and across the primary studies reported in the systematic reviews.

One very low-quality SR11 with evidence reported by the authors to be low quality due to trial design (i.e., mostly observational studies) reported that the rate of tobacco cessation from pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions conducted in the United States ranged from 3.98% to 77.14%, with follow-up ranging from one to six months.

One moderate-quality SR12 included four studies (one moderate quality, three weak quality, as assessed by the authors) that reported statistically significantly higher quit rates in the pharmacist-led interventions compared with the control (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario), and four studies (three strong quality, one weak quality, as assessed by the authors) that did not report a difference in quit rate between the intervention and control (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario).

One low-quality SR with meta-analysis7 which included studies with high and low risk of bias, reported that pharmacist-led interventions were associated with a statistically significantly higher likelihood of smoking abstinence compared with standard or usual care, however, this analysis combined RCTs with non-randomized studies. Subgroup analyses by study design (i.e., RCTs only), low risk of bias studies only, and objective measurement of smoking abstinence all demonstrated statistically significantly higher likelihood of smoking abstinence for pharmacist-led interventions compared with standard or usual care.

Cost-Effectiveness of Pharmacist-Led Interventions of Smoking Cessation

One very low-quality SR13 included cost-effectiveness studies regarding pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation, but did not assess the quality of the included studies. This SR provided a narrative description of the findings across the included studies, and in general pharmacist-led interventions were cost-effective for smoking cessation.13

Specifically, in the SR by Perraudin et al., five studies were included; four were from the United Kingdom and one was from Denmark. In the studies from the United Kingdom, pharmacist-led smoking cessation services were considered cost-effective over a short term (up to one year) from a National Health Service perspective compared to a self-quit scenario. The reported ICERs for the studies from United Kingdom ranged from £657 per additional quitter at 44 weeks to £9,762 per additional 52-week quitter.13 In the study from Denmark, pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation were found to be cost-effective compared to no intervention over a lifetime time horizon.13 The study from Denmark found an ICER of €1,672 per life-year gained but this increased to €11,880 for patients under 35 years old.13

Limitations

There were various limitations with the evidence in this report on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation.

A key limitation was the heterogeneity of the body of evidence. Within the primary studies contained within the four SRs7,11–13 there was substantial variation with regards to the pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions, including differences in the type, duration, and the frequency of the interventions. The multiple different approaches to pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions could affect the generalizability of the findings. There was also variation in the methods of assessment of smoking cessation within the primary studies in the SRs; some studies used biochemical measures (e.g., carbon monoxide levels), while other studies relied on self-reported change in smoking behavior. The use of self-reported measures of smoking abstinence may limit the reliability of the evidence.

This report was also limited by the quality of the body of evidence which limits confidence in the findings. This report contains evidence from two very low-quality SRs11,13 that did not conduct quality assessments of their included studies, one low quality SR with meta-analysis7 of primary studies that had both high and low risk of bias, and one moderate-quality SR12 with weak to strong quality studies .Many of the SRs did not provide summary statistics, but rather presented narrative summaries of the findings, making it difficult to determine the overall magnitude of effect for these interventions.

An additional gap in the evidence was the availability of information on different outcomes. The three clinical effectiveness SRs7,11,12 reported on smoking cessation, but no other clinical effectiveness outcomes were reported in the SRs, and none of the studies reported on adverse events.

All of the identified SRs were also conducted outside of Canada and some restricted inclusion to studies from particular geographical areas (e.g., Europe13 or the United States11). Healthcare systems, including the community pharmacist setting, vary between countries and these settings may not be reflective of the health system in Canada. Therefore, the generalizability of the results to the Canadian context is unclear.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

This report comprised three SRs7,11,12 regarding the clinical effectiveness of pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions, and one SR evaluating the cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions.13

For smoking cessation, this report contains evidence from three very low- to moderate-quality SRs7,11,12 with minimal overlap of primary studies. Mixed findings were reported for the effectiveness of pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation. One very low-quality SR11 reported substantial variation in the rate of tobacco cessation following pharmacist-led interventions (i.e., 3.98% to 77.14%), but the majority of this evidence was from low-quality observational studies. One moderate-quality SR12 that included weak- to strong-quality evidence included four primary studies with statistically significantly higher quit rates in the pharmacist-led interventions compared with the control (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario), and four studies that did not report any difference between the intervention and control groups (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario). The other low-quality SR with meta-analysis7 of studies with both high and low risk of bias reported a statistically significantly higher likelihood of smoking abstinence in pharmacist-led interventions compared with standard or usual care. This association remained when subgroup analyses were conducted for RCTs, low risk of bias studies, and objective measurement of smoking abstinence.7 No other clinical effectiveness outcomes, including adverse events, were reported in the SRs.

One very low-quality SR13 that did not evaluate the quality of the included cost-effectiveness studies, found that in general pharmacist-led interventions were demonstrated to be cost-effective compared to self-quit or no intervention in Europe.

Overall, the evidence suggested that patients who participated in pharmacist-led interventions experienced greater smoking cessation rates or no difference in smoking cessation rates in comparison to usual care or no intervention. No evidence from the SRs suggested that pharmacist-led interventions resulted in lower rates of smoking cessation. Pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions may be cost-effective.

The limitations of the included studies and of this report should be considered when interpreting the findings. The findings highlighted in this report come with a considerable degree of uncertainty. Further well-conducted RCTs comparing pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions with standard of care or no intervention may help to reduce uncertainty.

References

- 1.

George

J, Thomas

D. Tackling tobacco smoking: opportunities for pharmacists.

Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(2):103–104. [

PubMed: 24606241]

- 2.

- 3.

Chamberlain

C, Perlen

S, Brennan

S, Rychetnik

L, Thomas

D, Maddox

R, et al. Evidence for a comprehensive approach to Aboriginal tobacco control to maintain the decline in smoking: An overview of reviews among Indigenous peoples.

Systematic reviews. 2017;6(1):135. [

PMC free article: PMC5504765] [

PubMed: 28693556]

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

Thomson

K, Hillier-Brown

F, Walton

N, Bilaj

M, Bambra

C, Todd

A. The effects of community pharmacy-delivered public health interventions on population health and health inequalities: A review of reviews.

Prev Med. 2019;124:98–109. [

PubMed: 30959070]

- 7.

Saba

M, Diep

J, Saini

B, Dhippayom

T. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in community pharmacy.

J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(3):240–247. [

PubMed: 24749899]

- 8.

Mdege

ND, Chindove

S. Effectiveness of tobacco use cessation interventions delivered by pharmacy personnel: A systematic review.

Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(1):21–44. [

PubMed: 23743504]

- 9.

Peletidi

A, Nabhani-Gebara

S, Kayyali

R. Smoking cessation support services at community pharmacies in the UK: A systematic review.

Hellenic J Cardiol. 2016;57(1):7–15. [

PubMed: 26856195]

- 10.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, Mulrow

C, Gotzsche

PC, Ioannidis

JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 11.

O’Reilly

E, Frederick

E, Palmer

E. Models for pharmacist-delivered tobacco cessation services: A systematic review.

J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019. [

PubMed: 31307963]

- 12.

Brown

TJ, Todd

A, O’Malley

C, Moore

HJ, Husband

AK, Bambra

C, et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: A systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation.

BMJ open. 2016;6(2):e009828. [

PMC free article: PMC4780058] [

PubMed: 26928025]

- 13.

Perraudin

C, Bugnon

O, Pelletier-Fleury

N. Expanding professional pharmacy services in European community setting: Is it cost-effective? A systematic review for health policy considerations.

Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1350–1362. [

PubMed: 28228230]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Designs and Numbers of Primary Studies Included | Eligibility criteria | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Relevant Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

O’Reilly 2019 United States11 | Search: Systematic review of the literature from PubMed/MEDLINE and EBSCO databases, from July 2003 to April 2019. Also reviewed reference lists of key articles. Included studies: 16 studies:

- -

14 observational studies (8 retrospective studies and 6 prospective studies) - -

2 randomized prospective trials

Aim: summarize delivery models of pharmacist-led tobacco cessation services | Inclusion criteria: English language studies, patients 18 years of age and older using tobacco products; pharmacist-led tobacco cessation services in the United States; and the outcome of tobacco cessation. Exclusion criteria: not specified | Intervention: Tobacco cessation services should be managed by a pharmacist. The pharmacist could work independently, in tandem with another provider, or as part of a multidisciplinary team. Interventions varied by primary study and included face-to-face, telephone, or a combination of methods, as well as one-on-one encounters and group sessions. Sessions included appointment based or walk-in services, or both. Comparator: not required | Tobacco cessation |

Brown 2016 United Kingdom12 | Ten databases were searched from inception to May 2014. Also searched grey literature and trial registries, and contacted experts. Included studies: 8 relevant studies (12 studies for smoking cessation were identified in this systematic review):

- -

6 RCTs, 2 non-randomized studies

Aim: review the effectiveness of community pharmacy-delivered interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management. | Inclusion criteria: RCTs, non-RCTs, controlled before/after (non-randomized) studies, interrupted time series, and repeated measures studies. Any type of community pharmacy (i.e., pharmacy set in the community, which is accessible to all and not based in a hospital, clinic or online). Delivered intervention aimed at alcohol reduction, smoking cessation, or weight management; of any duration, based in any country and of any age. No restrictions on the type of comparator. Participants could be recruited from outside the pharmacy as long as the intervention was delivered in the pharmacy. Populations from included studies were adult patients in the community pharmacy setting from the UK, US, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Japan, and Denmark. | Any type of community pharmacy delivered intervention for smoking cessation (cannot be hospital, clinic or online setting), may include non-pharmacological support and/or pharmacological interventions Comparator: non-active control, usual care, or another type of active intervention, set in or out of the community pharmacy | Primary outcome: behavioural outcome of quit rate |

Perraudin 2016 Switzerland13 | Search: PubMed MEDLINE, Embase and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases from 2004 to August 6, 2015. 5 cost-effectiveness analyses were identified for smoking cessation Aim: Synthesize cost-effectiveness analyses on professional pharmacy services performed in Europe in order to contribute to current debates on their funding and reimbursement. | Inclusion criteria: Full economic evaluations or study-based/model-based study with RCT or observational data, published in the English language. Must be European patients in the community setting including those who are smokers. Must compare both the costs and the outcomes between at least a professional pharmacy services provided by a pharmacist and another strategy (usual care, no intervention or comparable service delivered by another provider). | Intervention: Various professional pharmacy services across the studies (one-on-one or group counselling, behavioral support, financial incentives in combination with NRT) Comparator: self-quit scenario (4 studies), no intervention (1 study) | Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) |

Saba 20147 Australia | Search: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts and ISI Web of Knowledge were searched for original-research English-language articles published in peer reviewed journals from inception to May 2013. Included studies: 3 RCTs and 2 non-randomized studies Aim: Evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacist-delivered smoking cessation interventions in assisting patients to quit | Inclusion criteria: RCTs, non-randomized studies, and controlled before-after studies of smoking cessation interventions performed with smokers that were conducted by a community pharmacist or within a community pharmacy setting, and reporting smoking abstinence as an outcome. Exclusion criteria: if the control group was not receiving standard or usual care or if the intervention and control groups received similar pharmacy services. | Intervention: Counselling by pharmacists varied by study, and included one-on-one and group sessions. Comparator: Standard of care or usual care | Primary outcomes: Smoking abstinence, measured by continuous abstinence or point prevalence Continuous abstinence = not smoking, not even a puff, throughout the specified period of follow-up. Point prevalence = not smoking, not even a puff, for the specified period leading up to a single point of follow-up Follow-up: ranged from 1 month to 12 months across the studies |

MA = meta-analysis; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; QALY = quality adjusted life-year; RCT = randomized controlled trial; UK = United Kingdom; US = United States.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR 25

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| O’Reilly 201911 |

|---|

Well-described research question and inclusion criteria Included both RCTs and NRSs Comprehensive search strategy, including reviewing the reference lists of key articles Study selection performed in duplicate Provided reasons for excluding studies Authors declared no conflicts of interest

| No written protocol Unclear whether data extraction was performed in duplicate No list of excluded studies provided Insufficient details provided on the included studies. The populations were not described, and comparators were poorly reported. Did not conduct an assessment of the risk of bias or the quality of the studies. Based on the non-randomized study design of most of the studies (14 of 16 studies) the level of evidence was considered low overall. Did not report sources of funding of primary studies

|

| Brown 201612 |

|---|

Research question and inclusion criteria were thoroughly described Protocol was registered and published Included RCTs and NRSs Comprehensive search strategy, including a search of the grey literature Study selection and data extraction performed in duplicate Provided reasons for excluding studies Satisfactory technique used for assessing risk of bias Reported the sources of funding for the primary studies Discussed the possibility of publication bias The authors declared no conflicts of interest

| |

| Perraudin 201613 |

|---|

Included economic evaluations of RCTs and NRSs Comprehensive list of databases searched Study selection and data extraction performed in duplicate Provided reasons for excluding studies The authors reported no conflicts of interest

| Research question and inclusion criteria were lacking detail No written protocol Did not search for grey literature No list of excluded studies provided Did not assess the quality or risk of bias in the included studies Did not report sources of funding for included studies

|

| Saba 20147 |

|---|

Well-described research question and inclusion criteria Comprehensive list of databases searched Included both RCTs and NRSs Study selection and data extraction performed in duplicate Provided reasons for excluding studies Interventions and outcomes well-described Satisfactory technique used for assessing risk of bias Conducted a subgroup analysis by study design and risk of bias Risk of bias was considered when discussing the results The authors reported no conflicts of interest

| No written protocol Did not search for grey literature No list of excluded studies provided Populations and comparators were lacking detail Did not report source of funding for included studies Unclear whether the authors were justified in combining some of the studies in the meta-analysis. RCTs and NRSs were combined in the main analysis, and substantial heterogeneity existed between all studies in terms of interventions and time points. Publication bias not reported

|

NRS = non-randomized study; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 4Summary of Findings Included Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| O’Reilly, 201911 |

|---|

- -

16 articles from the US were included - -

The comparator was unclear in most of the studies - -

Methods of pharmacist-led interventions included face-to-face or telephone, and both methods where some were individual and some were group sessions. - -

Tobacco cessation was measured by self-report or carbon monoxide and cotinine in saliva or urine at various time points (including at 1 month, 1.5 months, 3 months, and 6 months after completion of smoking cessation program). - -

Rate of tobacco cessation varied greatly between the studies ( ranging from 3.98% to 77.14%) - -

The timing of measurement ranged from one to six months post intervention. - -

Most of the studies (62.5%) measured tobacco cessation by self-report

| “Pharmacists participate in tobacco cessation services in a variety of manners and settings. This review demonstrates that pharmacists can empower patients to achieve abstinence. Owing to the lack of consistency in reporting and minimal studies with comparator groups, however, the true impact of pharmacist interventions for tobacco cessation remains unclear.” (p. 10)11 |

| Brown, 201612 |

|---|

- -

8 primary studies relevant to this report - -

Global quality ratings: strong for 3 studies, moderate for 1 study and weak for 4 studies.

- -

4 studies (3 RCTs, 1 non-randomized study; 3 weak quality, 1 moderate quality) reported statistically significantly higher quit rates in the pharmacist-led interventions compared with the control (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario) - -

4 RCTs (3 strong quality, 1 weak quality) did not report a difference in quit rate between the intervention and control (e.g., non-active control, usual care, self-quit scenario)

A pooled meta-analysis was conducted in the systematic review but included studies that were not relevant to this report (i.e., the intervention was a nicotine patch), and is not extracted. | “The evidence demonstrates that the community pharmacy is an appropriate and feasible setting to deliver a range of public health interventions. Community pharmacy-delivered smoking cessation interventions are effective and cost effective, particularly when compared with usual care.” (p. 16)12 |

| Saba 20147 |

|---|

- -

The smoking cessation interventions implemented involved providing advice and counselling to patients, either on a one-to-one basis (4 studies) or within group sessions (one study) - -

One intervention also used NRT alongside counselling. - -

Pharmacist-led counselling varied in nature across studies and included counselling based on computer software systems that generate individually tailored behavioural advice (2 studies); counselling based on the “Pharmacists’ Action on Smoking” model (1 study); and the “stage of change” model of smoking cessation (1 study) - -

the five studies included 6 different pharmacist-led interventions

Six different pharmacist-led interventions vs. standard or usual care:Incidence of smoking abstinence: RR = 2.17 (95% CI, 1.43 to 3.31) I2 = 54.1%, P = 0.054 (moderate heterogeneity) Incidence of smoking abstinence by subgroups: Abstinence validation: Validated by objective measurement: RR = 3.21 (95% CI, 1.81 to 5.71) I2 = 36.5%, P = 0.207 3 studies Validated by self report: RR = 1.66 (95% CI, 1.66 to 2.54) I2 = 31.9%, P = 0.230 3 studies Study Design RCTs: RR = 2.62 (95% CI, 1.53 to 4.47) I2 = 53.7%, P = 0.091 4 studies Non-randomized studies: RR = 1.44 (95% CI, 0.58 to 3.63) I2 = 65.6%, P = 0.088 2 studies Risk of Bias Low risk of bias: RR = 3.21 (95% CI, 1.81 to 5.72) I2 = 36.5%, P = 0.207 3 studies High risk of bias: RR = 1.66 (95% CI, 1.08 to 2.54) I2 = 54.1%, P = 0.230 3 studies | “The obtained results clearly highlight that pharmacist-delivered interventions can yield better abstinence rates as compared with minimal interventions/controls; however, the overall generalizability, sustainability and practice translation aspects need to be explored further using an implementation science approach and rigorous large-scale trials.” (p244) “This meta-analysis has established that the implementation of community pharmacy-based smoking cessation interventions can significantly impact abstinence rates” (p246) |

CI = confidence interval; CO = carbon monoxide; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; QALY = quality-adjusted life year; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RR = relative risk; UK = United Kingdom; US = United States.

Table 5Summary of Findings of Included Economic Evaluations

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Perraudin, 201613 |

|---|

- -

5 studies were identified comparing pharmacist-led smoking cessation services to self-quit, other services or no intervention - -

4 studies from the UK concluded that smoking cessation services were cost-effective from the National Health Service perspective over short term. - -

Each of the 4 studies reported ICER (no summary statistics were completed in the meta-analysis):

- -

“QUIT4U” (behavioural support, NRT, financial incentives, other stop smoking services): ICER = £2,296/12-month quitter

- -

One study from Denmark found pharmacist-led interventions for smoking cessation were cost-effective over a lifetime time horizon

- -

“Services at pharmacy” vs. no intervention: ICER = €1,672/life-year gained but increased to ICER = €11,880 in those who were under 35 years old

| “Our review provides arguments for the implementation of services at pharmacies aiming to improve public health, such as screening services or smoking cessation services according to whether or not the decision makers are willing to invest.” (p. 1360)13 |

ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; QALY = quality adjusted life-year.

Appendix 5. Overlap of relevant primary studies between Included Systematic Reviews

Table 6Overlap Between Included Systematic Reviews

View in own window

| Primary Study Citation | Systematic Reviews included in the report |

|---|

| O’Reilly, 201911 | Brown, 201612 | Perraudin, 201613 | Saba 20147 |

|---|

| Bock (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | | ✓ |

| Bauld (2011) | | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maguire (2001) | | ✓ | | ✓ |

| Sinclair (1998) | | ✓ | | ✓ |

| Afzal (2017) | ✓ | | | |

| Andrus (2007) | ✓ | | | |

| Augustine (2016) | ✓ | | | |

| Chen (2014) | ✓ | | | |

| Cope (2015) | ✓ | | | |

| Dent (2009) | ✓ | | | |

| Gong (2016) | ✓ | | | |

| Khan (2012) | ✓ | | | |

| Litke (2018) | ✓ | | | |

| Maack (2018) | ✓ | | | |

| Nikansah (2008) | ✓ | | | |

| Peterson (2013) | ✓ | | | |

| Ragucci (2009) | ✓ | | | |

| Roth (2005) | ✓ | | | |

| Shen (2014) | ✓ | | | |

| Crealey (1998) | | ✓ | | |

| Hoving (2010) | | ✓ | | |

| Mochizuki (2004) | | ✓ | | |

| Vial (2002) | | ✓ | | |

| Boyd (2009) | | | ✓ | |

| Cramp (2007) | | | ✓ | |

| Olsen (2006) | | | ✓ | |

| Ormston (2015) | | | ✓ | |

| Hodges (2009) | | | | ✓ |

| Isacson (1998) | | | | ✓ |

Appendix 6. Additional References of Potential Interest

Non-pharmacist-led smoking cessation interventions - Indigenous populations

Chamberlain

C, Perlen

S, Brennan

S, et al. Evidence for a comprehensive approach to Aboriginal tobacco control to maintain the decline in smoking: an overview of reviews among Indigenous peoples. Systematic reviews. 2017;6(1):135. [

PMC free article: PMC5504765] [

PubMed: 28693556]

Minichiello

A, Lefkowitz

AR, Firestone

M, Smylie

JK, Schwartz

R. Effective strategies to reduce commercial tobacco use in Indigenous communities globally: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:21. [

PMC free article: PMC4710008] [

PubMed: 26754922]

Perraudin

C, Bugnon

O, Pelletier-Fleury

N. Expanding professional pharmacy services in European community setting: Is it cost-effective? A systematic review for health policy considerations. Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1350–1362. [

PubMed: 28228230]

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Pharmacist-Led Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Sep. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.