NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Guise JM, Eden K, Emeis C, et al. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean: New Insights. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2010 Mar. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 191.)

This publication is provided for historical reference only and the information may be out of date.

Introduction

Quality assessment of individual studies is a critical and necessary step in conducting an evidence review. Quality assessment is an assessment of a study’s internal validity (the study’s ability to measure what it intends to measure). If a study is not conducted properly, the results that they produce are unlikely to represent the truth and thus are worthless (the old adage garbage in garbage out). If however, a study is structurally and analytically sound, then the results are valuable. A systematic review, is intended to evaluate the entire literature and distill those studies which are of the highest possible quality and therefore likely to be sound and defensible to affect practice.

Our senior advisory team reviewed the literature around quality assessment including:

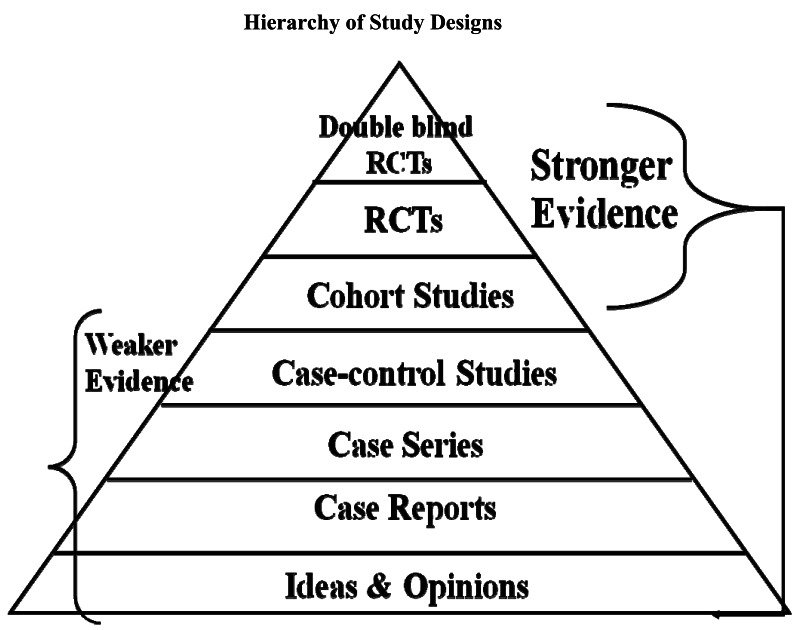

We were searching for a system that was able to evaluate the entire breadth of study designs as the Obstetric literature and vaginal birth after cesarean literature spans all study types. Using one system that is able to cover all study designs, makes it easier for the reader to understand quality assessments across study designed that are included in any given topic. For example, the topic of uterine rupture will include randomized controlled trials of induction of labor or other interventions but will also necessarily include cohort, case series, and case control literature.

We concluded that the quality assessment tool that was used in the last report remained the optimal choice for this current review. We felt that this was likely to be widely applicable across clinical reviews, and as such, we have developed a user’s guide to the quality assessment tool to increase reliability across staff.

Taxonomy of study designs1

Experimental designs

A study in which the investigator has control over at least some study conditions, particularly decisions concerning the allocation of participants to different intervention groups.

Randomized controlled trial

Participants are randomly allocated to intervention or control groups and flowed up over time to assess any differences in outcome rates. Randomization with allocation concealment ensures that on average known and unknown determinants of outcome are evenly distributed between groups.

Observational designs

A study in which natural variation in interventions (or exposure) among study participants is investigated to explore the effect of the interventions (or exposure) on health outcomes.

Cohort study

A follow-up study that compares outcomes between participants who have received an intervention and those who have not. Participants are studied during the same (concurrent) period either prospectively or, more commonly, retrospectively.

Case-control study

Participants with and without a given outcome are identified (cases and controls respectively) and exposure to a given intervention(s) between the two groups compared.

Cross-sectional study

Examination of the relationship between disease and other variables of interest as they exist in a defined population at one particular time point.

Case series

Description of a number of cases of an intervention and outcome (no comparison with a control group).

Randomized Controlled Trials Table Example

| Quality Criteria | Study, Year | Random assignment | Allocation concealed | Groups comparable at baseline & maintained | Eligibility criteria specified | Blinded: Outcome Assessors/Care Provider/Patient | Report of attrition Differential loss to follow-up | Analysis considerations | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What should be in the cell Definitions | First author, Year of Publication | Y/N/Unclear Yes -computer-generated random numbers -random numbers tables No -use of alternation -case record numbers -birth dates -days of the week -horoscope Unclear reports study as randomized, but provides no details on approach or not reported | Y/N/Unclear Yes -centralized or pharmacy- controlled serially-numbered identical containers -on-site computer based system with a randomization sequence that is not readable until allocation No-open random numbers lists -serially numbered envelopes(even sealed opaque envelopes can be subject to manipulation) Unclear not reported or reports study as concealed, but provides no details on approach | Y/N/Unclear Yes -comparison groups are balanced for relevant baseline characteristics, either described in the text or in a table -comparable groups were maintained throughout the study No (if no, state reason) -there are noted differences between the groups at baseline -authors excluded a group of people after they were randomized Unclear does not state that groups were different, but does not provide data to allow reader to compare groups on baseline characteristics | Y/N Yes -authors layout explicit eligibility criteria in the methods section -authors reference another article for methods and we are able to pull the information from that article No -authors imply eligibility criteria, but do not explicitly state it | Y/N/Unclear Please note: answer for each person; outcome assessors, care providers and patients Yes -Blinding is used to keep the participants investigators and outcome assessors, ignorant about the interventions which participants are receiving during a study. Blinding of outcome assessment can often be done even when blinding of participants and caregivers cannot. Blinding is used to protect against performance bias and detection bias. It may also contribute to adequate allocation concealment No-open label -un-blinded Unclear reports as ‘blind’ or ‘double blind’ but no details are provided | Attrition rate=% Differential loss to follow-up=% Report the actual attrition rate, per group -≤20% - Good -≤40% - Fair Calculate the differential loss to follow-up | Y/N/Unclear Yes -ITT analysis is followed, not only described but actually followed in the results section -included all who were randomized in the analysis -≤5% missing data without including them in the analysis No -specifically exclude people from the analysis -conduct ONLY a per protocol analysis Unclear reports ITT, but provides no details of who is in analysis | Good/Fair/Poor |

Randomized Controlled Trials Descriptors

Random assignment – The process by which study participants are allocated to treatment groups in a trial. Adequate (that is, unbiased) methods of randomization include computer generated schedules and random-numbers tables.

Allocation concealed – The process by which the person determining eligibility, consent, and enrollment is unaware of which group the next patient is to be assigned.

Groups comparable at baseline & maintained - The researchers need to explicitly describe their groups at baseline and how they may or may not differ on important prognostic factors. These types of comparable groups must be maintained throughout the study as well. This becomes very important and can be tricky to assess. We know that some women who end up with a cesarean will have opted for a trial of labor and some who opted for a cesarean prior to trial of labor will go into labor. Thus issues such as inclusion from intended cohort and intention to treat analyses are important.

Eligibility criteria specified – The researchers need to be explicit in laying out the eligibility criteria. This will include what inclusion criteria needed to be met to be eligible for the study as well as the reasons why they excluded particular individuals. This information is important to determine generalizability of the study.

Blinded: Outcome Assessors/Care Provider/Patient – A way of making sure that the people involved in a research study — participants, clinicians, or researchers —do not know which participants are assigned to each study group. Blinding usually is used in research studies that compare two or more types of treatment for an illness. Blinding is used to keep the participants, investigators and outcome assessors ignorant about the interventions which participants are receiving during a study. Blinding of outcome assessment can often be done even when blinding of participants and caregivers cannot. Blinding is used to protect against performance bias and detection bias. It may also contribute to adequate allocation concealment.

Report of attrition/Differential loss to follow-up – For every study, some proportion of participants is likely to dropout or be lost to follow-up due to a number of reasons. Loss to follow-up occurs when there is a loss of contact with some participants, so that researchers cannot complete data collection as planned, and do not know why the participants discontinued. Loss to follow-up is a common cause of missing data, especially in long-term studies. An acceptable attrition rate is ≤ 20% for a good quality rating and ≤ 40% for a fair quality rating.

Analysis considerations – The use of data from a randomized controlled trial in which data from all randomized patients are accounted for in the final results. Trials often incorrectly report results as being based on intention to treat despite the fact that some patients are excluded from the analysis. If co-interventions occurred the researchers need to describe how these were handled in the analysis.

Cohort Studies Table Example

| Quality Criteria | Study, Year/Design | Assembly of Groups | Maintenance of comparable groups | Outcome measures reliable & valid | Outcome assessor blind to exposure status | Missing data | Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Consider/adjust for potential confounders (obstetric conditions) | Clear definition of prognostic factors* | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What should be in the cell Definitions | First author, Year of Publication Study design as determined by investigator | Y/N/Unclear Yes<br>-authors layout explicit eligibility criteria in the methods section -authors reference another article for methods and we are able to pull the information from that article No -authors imply eligibility criteria, but do not explicitly state it | Y/N/Unclear This is analogous to ITT Yes -comparison groups are balanced for relevant baseline characteristics, either described in the text or in a table -relevant, important prognostic factors are similar across groups comparable groups are maintained throughout the study No (if no, state reason) -there are noted differences between the groups at baseline Unclear does not state that groups were different, but does not provide data to allow reader to compare groups on baseline characteristics | Y/N/Unclear Yes -validated, standard measurement used No -study uses questions they came up with, but have not validated or standardized Unclear There is mention of a measure used, but it is not described | Y/N/Unclear Studies should attempt to decrease bias in their assessment of data and need to explicitly state it Yes - the researcher recording outcome measure is looking only at outcome data, separated from intervention data | Overall differential loss to follow-up=% Report the actual attrition rate, per group - ≤ 20% - Good - ≤ 40% - Fair Calculate the differential loss to follow-up | Y/N/Unclear Has enough time passed to allow measured outcomes to occur? | Y/N/Unclear/NA Consider Yes -descriptions of potential confounders are noted -the authors describe confounders that they are aware of in the groups No no mention of potential confounders Adjust Yes statistical analysis conducted to minimize the affect of potential confounders No no statistical analysis is mentioned | Y/N/Unclear | Good/Fair/Poor |

- *

For prediction modeling studies only.

Cohort Studies Descriptors

Assembly of groups– In a cohort study, the assembly and maintenance of comparable groups is critical. Sometimes you will hear people talking about inception cohort that is the vision of a group of patients who represent the target population. In most intervention studies, you would want the intervention group to be as similar to the placebo group as possible with the only exception being the intervention. If this is sound, then whatever differences you measure between intervention and non intervention should be based upon the intervention itself. This issue can be difficult in obstetrics, particularly relating to delivery as the intervention in that, patients often self select to groups and there may be systematic reasons why people would choose different options which may also contribute to outcomes. Nonetheless, our goal in a systematic review is to ask were the groups assembled for cesarean versus trial of labor similar to each other. That is, would the group that had the cesarean have been eligible for a trial of labor in the first place? If the group who had a cesarean all had placenta previas, this population would not be eligible for a trial of labor and there are ways in which the group with placenta previa would be expected to differ in outcomes regardless of choice of intervention. The first test should be to examine the populations, look at whatever groups were systematically removed from the cohort assembled, and ensure that what remains in the TOL and Cesarean group are otherwise comparable.

Maintenance of comparable groups – This also becomes very important and can be tricky to assess. We know that some women who end up with a cesarean will have opted for a trial of labor and some who opted for a cesarean prior to trial of labor will go into labor. This topic is analogous to intention to treat analysis. The ideal cohort study would keep the patients in their original groups e.g. trial of labor versus repeat cesarean and report outcomes based upon that “inception cohort.” Doing this allows the study to report on outcomes for real experience that include adverse effects. It may be easier to understand the importance of this by looking at what happens if you don’t follow this. A VBAC study takes all women who intend trial of labor at 35 weeks and then reports on repeat cesarean without labor as the cesarean comparator and places the patients instead into the trial of labor groups reasoning that this group underwent labor. The outcome profile for the cesarean group is likely to be unrealistically positive in that labor increases the opportunity for infection, fetal intolerance of labor etc. Similarly, what a clinician can tell a patient is only what their experience would be if they chose cesarean and never went into labor rather than what the patient and clinician would like to know, what are the chance that I might go into labor anyways before my scheduled cesarean and what would be the implications for that. This maintenance must be maintained through analysis.

Outcome measures reliable and valid – Were the researchers clear and specific about the outcome measures? They should have identified the outcome they were attempting to identify, and then identify the measure(s) they were using to capture that outcome. This may for example, be ICD-9 codes in a study using a database that includes these codes. In this case, the researchers should identify how they determined the validity and reliability of these codes for the outcome measure of interest. If the outcomes were clinical measures abstracted from patient charts, the determination of an outcome should be well defined, and there should be indication that some assessment of the validity and reliability of decisions made by those making the determinations. In the best studies, the researchers will discuss why they selected specific outcome measures, for example, why they selected the HAM-D scale rather than the MADRS scale to measure depression, what change on the scale indicated clinically meaningful improvement or response, and so on.

Outcome assessors blind to exposure status – Were the outcome assessors blinded to which group the patient belonged? Those making determinations of whether an outcome occurred or not should ideally be unaware of which group that patient was in. This can be achieved in most cases. When the outcomes are being assessed retrospectively, the researcher recording outcome measure should be looking only at outcome data, separated from intervention data. If this is truly not possible, for example, the outcome data are described in such a way that the group the patient is in is apparent, then researchers who are not aware of the study purpose at the time of abstracting the outcome measure data can be employed. Blinding of outcome measure assessment is important even when it seems like the determination of the outcome is black and white. Many outcome assessments are in fact subjective, because the data are not perfect such that judgments have to be made along the way. While identifying mortality may be quite clear in most cases, there are situations where the data may be less reliable. More difficult is identifying the cause of death, if that is an outcome measure.

Missing data – For every study, some proportion of participants is likely to dropout or be lost to follow-up due to a number of reasons. Loss to follow-up occurs when there is a loss of contact with some participants, so that researchers cannot complete data collection as planned, and do not know why the participants discontinued. Loss to follow-up is a common cause of missing data, especially in long-term studies. An acceptable attrition rate is ≤ 20% for a good quality rating and ≤ 40% for a fair quality rating.

Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur – Was the follow-up period long enough? The researchers should indicate that they have thought through the disease process in detail when designing their study, such that the period of follow-up is long enough to allow the outcome to occur. If the outcome is mortality associated with hepatitis C, then a follow-up period of only several weeks is likely to be inadequate. If the researchers have not indicated reasoning for their selection of follow-up period, then you need to consider this determination.

Consider/adjust for potential important confounders – A confounder is a characteristic of study subjects that is a common cause of the exposure and the outcome. Researchers need to identify what potential confounders are possible given their study and when possible adjust for these confounders using statistical analysis.

Clear definition of prognostic factors* – In addition to these quality criteria, the evaluation of prediction modeling studies required that they provided a clear definitions of prognostic factors (1 extra criterion). The most important criteria for these studies were: comparable groups that included clear inclusion and exclusion criteria; clear definitions of the prognostic factors; adjustment (as needed, for studies without comparable groups) for confounders. To achieve a good rating, minimally, the study had to meet these three ratings. A study with comparable groups and no need for adjustment could still meet this standard. For studies that only met 2 of these 3 criteria, the highest rating they could achieve was fair.

Case-Control Studies Table Example

| Quality Criteria | Author, Year | Explicit definition of cases | Disease state of the cases similar & reliably assessed | Case ascertainment reliable, valid & applied appropriately | Non-biased selection of controls | Cases/controls: comparable confounding factors | Study procedures applied equally | Appropriate attention to confounders (consider & adjust) | Appropriate statistical analysis used (matched, unmatched, overmatching) | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What should be in the cell Definitions | First author, Year of Publication | Y/N Authors must clearly state how they defined who is considered a case. | Y/N/Unclear Cases should be similar in respect to time course of disease; this may include capturing all cases along a spectrum or focus on cases at a similar point in their progression of the disease/condition. | Y/N/Unclear | Y/N/Unclear Yes Controls randomly assigned | Y/N/Unclear Were they matched on important factors (i.e., age, SES, # of prior C/S, etc)? | Y/N/Unclear Are the procedures & measurement of exposure accurate & applied equally? | Y/N/Unclear/NA Consider Yes -descriptions of potential confounders are noted -the authors describe confounders that they are aware of in the groups No no mention of potential confounders Adjust Yes statistical analysis conducted to minimize the affect of potential confounders No no statistical analysis is mentioned | Y/N/Unclear | Good/Fair/Poor |

Case-Control Studies Descriptors

Explicit definition of cases – It is important to ensure that the authors clearly state how they defined who would be considered a case and that these cases are determined by outcome (e.g. cancer). A case definition may not be a definitive health outcome but rather an intermediate outcome such as in the case of uterine rupture for obstetric research.

Disease state of the cases similar and reliably assessed – When there is a spectrum of disease such as in the case of cancer or neurologic injury of a fetus, considerations of whether the cases are similar to one another in relation to time course of disease is important to consider. Depending on the stated objective, you may wish to capture all cases along the spectrum or to focus such that cases are at a similar point in their progression of disease.

Case ascertainment reliable, valid and applied appropriately – How did the authors assess whether the patient was a case, how reliable is this method, and how did they ascertain cases? For example in the case of leukemia research use of ICD-9 codes, not clearly stated, histological evaluation by 2 pathologists, excluded all adopted children (this may be important if you were evaluating the effect of exposure to radiation and this was geographically represented rather than biologically inherited). In the obstetric literature, case control studies have been conducted on cases of uterine rupture. Studies have used ICD-9 codes to ascertain cases, however there are several that may apply. Some of the codes are more specific to uterine rupture while others include not only uterine rupture but also surgical extension of uterine incisions, which is not a uterine rupture. Studies that include the latter would have a consistent mechanism to apply but research has shown that the latter code is unreliable to ascertain cases. The next question once you know what method people use to identify cases is where they apply them. For example, hospitals’ discharge summaries in a single institution, identification from a cancer registry, governmental databases, laboratory pathological diagnoses. Similar to the conceptual cohort idea of the cohort study this is where you are asking whether the methods are likely to capture all cases that would be of interest.

Nonbiased selection of controls – The issue of ensuring that controls are comparable to cases is critical to the quality and reliability of a case control study. Selecting a noncomparable control may skew the results and make then uninterruptable.

Cases/controls: comparable confounding factors – The cases and controls should be comparable with respect to potential confounding factors. Otherwise, the results must be interpreted with this bias in mind.

Study procedures applied equally - Are the procedures & measurement of exposure accurate & applied equally? All measurements should be applied to both cases and controls equally and accurately.

Appropriate attention to confounders (consider & adjust) - A confounder is a characteristic of study subjects that is a risk factor (determinant) for the outcome to the putative cause, or is associated (in a statistical sense) with exposure to the putative cause. Researchers need to identify what potential confounders are possible given their study and when possible adjust for these confounders using statistical analysis.

Appropriate statistical analysis used (matched, unmatched, overmatching) – Was the method used for statistical analysis appropriate? Did the researchers match their controls and cases appropriately? Beware of overmatching by researchers as well, when they match the subjects on too many variables making the results uninterruptable as well.

Case Series Studies Table Example

| Quality Criteria | Author, Year | Representative sample selected from a relevant population | Explicit definition of cases | Sufficient description of distribution of prognostic factors | Follow-up long enough for important events to occur | Outcomes assessed using objective criteria/blinding used | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What should be in the cell Definitions | First author, Year of Publication | Y/N/Unclear Is the population examined relevant to the disease and age group? or atypical? Yes -randomly selected from registry -consecutive patients No -self-selected volunteers -investigator selected | Y/N Yes -authors layout explicit definitions for their cases -authors reference another article for methods and we are able to pull the information from that article No -authors imply definition, but do not explicitly state it | Y/N/Unclear/NA | Y/N/Unclear Did the authors allow enough time for the outcomes to occur. | Y/N/Unclear Do the methods describe the measures in detail; are they reliable/valid; are references provided? | Good/Fair/Poor |

Case Series Studies Descriptors

Representative sample selected from a relevant population – For case series studies, the cases being selected must be representative of the overall population. This will require the judgment of experts in the particular subject matter being studied to understand if the cases represent the broader population they are being drawn from. The researchers need to describe the overall population and how their cases are a representative sample of this overall population.

Explicit definition of cases – It is important to ensure that the authors clearly state how they defined who will be considered a case and that these cases are determined by outcome (e.g. cancer). A case definition may not be a definitive health outcome but rather an intermediate outcome such as in the case of uterine rupture for obstetric research.

Sufficient description of distribution of prognostic factors – A prognostic factor is a situation or condition, or a characteristic of a patient, that can be used to estimate the chance of recovery from a disease or the chance of the disease recurring. The researchers should explicitly describe the prognostic factors that are relevant to the group(s).

Follow-up long enough for important outcomes to occur – Was the follow-up period long enough? The researchers should indicate that they have thought through the disease process in detail when designing their study, such that the period of follow-up is long enough to allow the outcome to occur. If the outcome is success of a trial of labor in a pregnant woman with a previous cesarean delivery, then a follow-up period of only several hours is adequate. However, if the outcome is neurological sequelae in the infant, then a much longer period of follow-up is necessary, possibly years are required. If the researchers have not indicated reasoning for their selection of follow-up period, then you will need to consider this determination.

Outcomes assessed using objective criteria/blinding used – Were the outcome assessors blinded to which group the patient belonged? Those making determinations of whether an outcome occurred or not should ideally be unaware of which group that patient was in. This can be achieved in most cases. When the outcomes are being assessed retrospectively, the researcher recording outcome measure should be looking only at outcome data, separated from intervention data. If this is truly not possible, for example, the outcome data are described in such a way that the group the patient is in is apparent, then researches who are not aware of the study purpose at the time of abstracting the outcome measure data can be employed. Blinding of outcome measure assessment is important even when it seems like the determination of the outcome is black and white. Many outcome assessments are in fact subjective, because the data are not perfect such that judgments have to be made along the way. While identifying mortality may be quite clear in most cases, there are situations where the data may be less reliable. More difficult is identifying the cause of death, if that is an outcome measure.

Rating Determinations2

Good (low risk of bias). These studies have the least bias and results are considered valid. A study that adheres mostly to the commonly held concepts of high quality including the following: a formal randomized controlled study; clear description of the population, setting, interventions, and comparison groups; appropriate measurement of outcomes; appropriate statistical and analytic methods and reporting; no reporting errors; low dropout rate; and clear reporting of dropouts.

Fair. These studies are susceptible to some bias, but it is not sufficient to invalidate the results. They do not meet all the criteria required for a rating of good quality because they have some deficiencies, but no flaw is likely to cause major bias. The study may be missing information, making it difficult to assess limitations and potential problems.

Poor (high risk of bias). These studies have significant flaws that imply biases of various types that may invalidate the results. They have serious errors in design, analysis, or reporting; large amounts of missing information; or discrepancies in reporting.

References

- 1.

- Adapted from: Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment. 2003;7(27):iii–x. 1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Reference Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, Version 1.0. Rockville, MD : 2007. [PubMed: 21433403]

- Quality Rating Criteria - Vaginal Birth After Cesarean: New InsightsQuality Rating Criteria - Vaginal Birth After Cesarean: New Insights

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...