NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al., editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 1: Assessment). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008 Aug.

Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 1: Assessment).

Show detailsAbstract

The 26,000 close call reports collected through The University of Texas Close Call Reporting System (UTCCRS)—funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and a research project of The University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice—are described in this article, as well as a unique approach to increase reporting. The UTCCRS system was designed as a voluntary and anonymous reporting tool to collect valuable information about close calls. Information from close call reports informed the development of targeted interventions and ultimately led to the identification and implementation of quality improvement projects. To date, the system has received over 26,000 reports. Initiatives implemented to increase the number of reports included an innovative Good Catch Program© based on a baseball theme. This initiative was recently awarded the 2007 National Patient Safety Foundation’s “Stand Up for Patient Safety” Management Award.

Introduction

Although error reporting has been widely substantiated in the literature as an integral part of safety programs, barriers to implementation continue despite substantial efforts to increase reporting. Although close call or near miss reporting is recognized as a proactive means of error prediction, an increase in reporting has not been achieved consistently or sustained in many of the piloted or implemented safety programs in health care.1

Acquiring, aggregating, and acting on near-miss or close-call reports requires a program of awareness and rewards as demonstrated in the “Good Catch Program.” In the experience of this program, a concerted effort to raise awareness is necessary. The Good Catch Program was established in the organizational culture by relating the reporting process to an easily understood, common, and non-threatening sporting event.

In a 2004 patient safety article, Edmondson wrote, “Organizations that systematically and effectively learn from the failures that occur in the care delivery process, especially from small mistakes and problems, rather than from consequential adverse events, are rare.”1 The timely review and rating of close calls can provide valuable diagnostic information for insight into a system’s vulnerabilities, facilitate the identification of areas for system improvement, and enable rapid systematic correction.2,3,4

The University of Texas Close Call Reporting System (UTCCRS)5 was established within the Institute for Healthcare Excellence at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center to facilitate a proactive approach to preventing errors. The initial low volume of reports submitted by employees was recognized as a barrier to learning from the system. A creative, effective strategy was needed to engage employees in reporting close calls.

Methods

A literature search was conducted to identify strategies to significantly increase reporting. Topics identified from the literature search incorporated into the program design included understanding the role of microsystems within organizations and the importance of engaging frontline employees in safety reporting, understanding why employees do and do not report, identification of essential educational components to facilitate employee participation, the role of executive leadership participation in the program, the feedback process, and employee recognition.

The Importance of Microsystems

Poniatowski and colleagues6 described organizations as macrosystems that are built upon many interrelated microsystems. Most actual or potential errors in a hospital setting, which directly affect patient care outcomes and negatively affect patient safety, likely occur at the microsystem level.7,8 Therefore, to capture safety concerns at the time they are identified, it would be necessary for the program to engage frontline employees of inpatient nursing units as reliable sources of information.9,10,11 However, acquiring reports from the microsystem level has been hindered by several factors. A study of nurses’ medication error reporting revealed four factors that explain why employees may not report errors: (1) fear, (2) disagreement over whether an error occurred, (3) administrative responses to errors, and (4) the effort required to report an error.12

Fear

In order to overcome employee fears and concerns associated with reporting, a culture of trust must be promoted within an organization.7,8,9 This can best be accomplished by eliminating the possibility of assigning blame or initiating disciplinary action related to reporting.7,13,14,15 Employees must be made to feel safe to report so that safety concerns can be identified and the systems can be strengthened.10,16,17

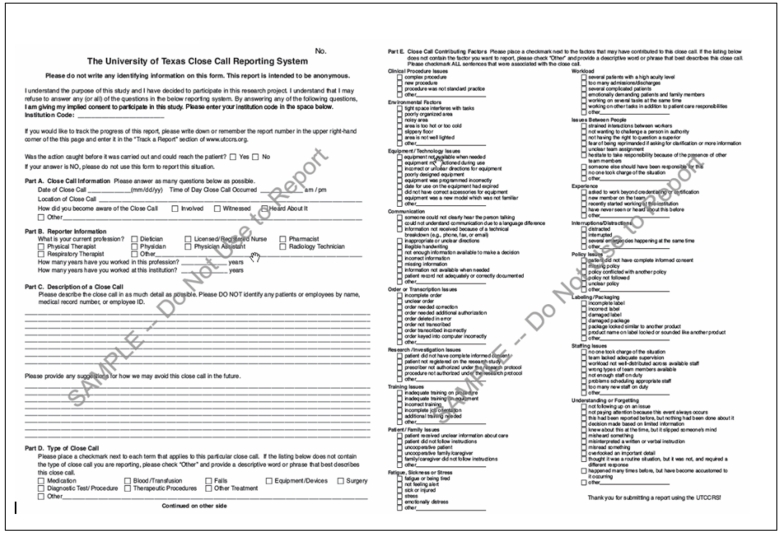

In close call reporting, employees are asked to report situations for which they have already effectively intervened to prevent error. The definition of a close call, as found on the reporting tool, is “a situation that does not cause harm nor reach the patient.”5 The UTCCRS was designed as an anonymous reporting system to protect employees’ identity.13 Reports are screened outside the hospital’s risk and quality department by an impartial third party group of experts. Names, room numbers, medical record numbers, and any other identifying information are scrubbed from reports (if they have been entered by an employee). The system does not allow individual reporters to be identified or contacted. However, when a report is entered, a unique tracking number is automatically generated. The employee can use this unique tracking number to re-access the system and review followup notes if they desire feedback (Appendix 1).

Defining Actual and Potential Errors

To ensure that appropriate information would be submitted to UTCCRS, it was important to clearly define close calls (“Good Catches”) in the educational component of the program. Hritz, et al.,18 recommended that reporting systems and improvement interventions continually focus on building an awareness of the occurrence of errors through identification and reporting. To address this recommendation, examples of reports that demonstrated the differences between actual and potential errors were developed, and a list of potential error examples was created as a reference tool. The educational plan incorporated the instruments as exemplars and handouts.

The Importance of Executive Leadership Support

Initiatives led by hospital executives to improve an organization’s culture of patient safety can result in a profound and lasting change in the organization’s safety culture.19,20 Leaders need to visibly guide and support staff through reporting systems that involve recognition and rewards.21 Therefore, mechanisms for administrative leaders to show support and motivate employees are essential to the Good Catch Program. Continual recognition of progress, shared safety success stories, and celebrations of achievements were incorporated into the program design. Building recognition and reward from executive leaders, including associated financial support, was therefore identified as another important program component.

Recognition of employees’ personal ability to effect change was also identified. Plans to recognize patient safety champions with safety award certificates and “Most Valuable Player” (MVP) recognition were included in program design. This was recognized as a needed improvement based on feedback from employees and executives after the original launch of UTCCRS. Barriers and interventions to surpass them are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of barriers and interventions.

The Good Catch Program

A baseball theme was used to organize inpatient nursing units into teams and group them in one of four Divisions of an Inpatient Nursing League. A report accepted into the UTCCRS resulted in a point for the team. A unit code generated points for each team, while maintaining the reporter’s anonymity. The team and “game” approach engaged frontline staff in a fun, friendly competition on inpatient nursing units as they reported Good Catches identified in daily practice.

As each team joined the league, unit-based in-services were provided using a PowerPoint™ presentation and handouts that included definitions and examples of close calls. Information provided during the educational sessions included definitions of safety and preventable harm; descriptions of a systems view of errors; theories and perspectives about errors in health care; description of UTCCRS with instructions for entering data; and examples of advances in patient safety and human factors in design.

To maintain the program’s baseball theme, close calls were renamed “Good Catches.” Each unit decided on a team name, and representatives from each team served on a workgroup that met as needed to address “game” strategies. Creative team names included: SCRUBS: Safety Created Regularly & Uniformly by Staff; PEDI: People Effectively Decreasing Incidents; OOPS: Outstanding Outcomes in Patient Safety; The Hazard Hunters; STOPS: Staff Thinking of Patient Safety; and The Awareness All-stars.

Quality Improvement Department representatives and administrators of the UTCCRS were included as workgroup members. Team representatives were assigned the important position of Patient Safety Champion and were given responsibilities to facilitate communication of program information to their team members. Weekly scoreboards were e-mailed to representatives for posting on the units. A friendly competition between units was promoted by encouraging team members to submit reports and earn points for their team.

The team in each Division that entered the greatest number of Good Catch reports during a “game” was recognized in the institution’s Nursing News & Information weekly newsletter and awarded a pizza party. In addition, MVPs were identified on each team, and each received a patient safety champion award certificate signed by executive leadership. An Inpatient League World Series is currently in the planning stages. The World Series event will provide a forum for organizational level recognition of employee participation in the Good Catch safety initiative.

Executive Leadership Support

The Vice President of Nursing served as the Inpatient League Commissioner to ensure that executive leadership was provided. Four department directors served as head coaches for each Division to enhance visible administrative support for the program. Every 6 months, a new Division of four to five nursing units was formed. Education and mentorship were provided for all team members until all four Divisions were participating in the program.

The Vice President of Nursing visited each unit approximately 4 months after they joined the program and distributed Good Catch pins to participating team members. Team members prepared patient safety storyboards and shared information about the different types of Good Catches. Several teams had t-shirts made with a team logo and wore baseball caps during the unit visit. One team decorated the staff lounge as a dugout. In addition, incentives for nurses (e.g., “Safety Awards”) were sponsored and promoted by executive leadership to acknowledge individual nurses as patient safety champions during each 6-month game.

Results

The University of Texas Close Call (UTCCRS) reporting system was launched at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in May of 2003. Dissemination activities included various intranet and e-mailed notices and articles and brief in-services on participating units. In October 2005, the system was opened to all units and became part of the in-service information given to all employees. A single portal icon (named “Safety Reports”) was placed on all computer desktops to allow users to access either the online incident reporting system or to report a close call through UTCCRS.

The Good Catch program was piloted on five acute care units beginning December 12, 2005. Between December 2005 and July 2007, 25,921 reports were received, with a dramatic increase in reporting ocurring each time a “season” began or new leagues opened. Each season runs from January to June and from July to December (Figure 1).

Figure 1

UTCCRS “Good Catch Report,” count by month: December 2005–July 2007.

Categories Reported in Good Catch

The reporting categories in UTCCRS are not mandatory; the reporter can choose one category or many categories or even not to categorize. The total count of categories (26,622) was higher than the total number of reports received (25,921) because reporters chose several categories in some reports (Figure 2).

Figure 2

UTCCRS “Good Catch Report,” count by category: December 2005–July 2007.

Contributing Factors

The contributing factors list in the UTCCRS was developed in an extensive consensus-building exercise as the system was developed13 (Appendix 2). The total count of factors identified in Figure 3 (29,273) is greater than the total number of reports received (25,921) (Figure 1) because there are no mandatory reporting fields, and reporters might have chosen more than one (Figure 3).

Figure 3

UTCCRS “Good Catch Report,” count by contributing factor: December 2005–July 2007.

Conclusion

Sensemaking of Good Catches

Battles, et al., described safety data as requiring “sensemaking” conversations based on data acquired from detection tools, such as reporting mechanisms.22 Sensemaking also assists in categorizing and prioritizing the risk knowledge that comes from reported events. This essential component of an organization’s safety plan is necessary to create a proactive culture and proactive intervention for safety.10 Close calls—or good catches—are included in the safety data that contribute to an institution’s safety plan and interventions.

Aggregating themes from the Good Catch Program has informed several quality initiatives. The Good Catch program has generated a number of safety interventions based upon collected data and the “sense” made of these reports. Many of the reports provided data that confirmed systems mechanisms were in place to prevent actual errors from occurring. Examples of system error prevention mechanisms include: medication administration record (MAR) reconciliation; 8-, 12-, or 24-hour chart checks; and increasing double-checks on reported high-alert medications. Multidisciplinary teams have utilized good catch data to generate short- and long-term quality improvement projects.

In a health care organization, a large collection of good catches provides challenges. The first challenge is to familiarize the organization with the volume, purposes, and nature of safety reporting. The number of reports is daunting when each one is considered individually, and certainly few organizations maintain the resources to respond equally to each report. Battles, et al., describe the analytical tools necessary to assist staff working with such data to “overcome the limitations of the individual mind” so sense can be made of larger data sets.22 After “sense” has been made, the challenge is to provide interventions based on such reports, so that changes can be made to reduce system-level vulnerabilities found in the data.10

Challenges

Initially, many of the teams expressed concerns by questioning whether a high number of good catches might “look bad” for a unit. Positive feedback was provided to assure teams that higher numbers of submitted reports supported a greater focus on patient safety. Also, because historically reports were submitted only when an actual error had occurred, a “change in thinking” was required. Some teams raised questions about why units with more submitted reports were being recognized, while units that just “fixed” concerns but did not report them were not being rewarded. This question provided the opportunity to educate employees that although they continually intervened to ensure safe care, the “fixes” needed to be reported so that systems issues could be identified and addressed.

Program coordinators and administrative leadership affirmed that positive recognition was being provided to units that were submitting a high volume of reports. Reports were communicated as “nursing interventions for patient safety” and close call reporting was promoted as an opportunity for employees to document their important role in the front line of patient safety.

By successfully increasing the numbers of reports submitted to the University of Texas Close Call Reporting System, the Good Catch program has provided a supporting mechanism for the organization to systematically and effectively learn from safety interventions implemented on the front line. Gaining insight about areas of potential vulnerability has allowed the organization to be proactive with interventions to eliminate risk for potential errors and to decrease the possibility of an actual error occurring. Each Good Catch has contributed to safer patient care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant 1PO1 HS1154401). We thank the following individuals for their leadership and support of the Good Catch program: Barbara Summers, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center; and Eric Thomas, The University of Texas – Houston Medical School.

Appendix 1. Close Call Reporting System Features List

Close Call Gathering:

- □ Allows hospital employees a place to anonymously report close calls that they witnessed, took part in, or simply heard about.

- □ Employee can enter suggestions on how to prevent this close call from happening in the future.

- □ Employee can track the progress of his or her report through a system-generated tracking number and password that only the employee can access.

- □ A qualifying question will be asked before reports are entered to detect any occurrence that actually reached the patient; in that case, the employee will be redirected to a form or process defined by each participating hospital.

Reports:

- □ Reports entered from any hospital will be available to the administration of that hospital only.

- □ Each participating hospital will be assigned a secure Web site for administrators to receive statistics on reports entered from their hospital and do a comparison to all reports entered.

Quality Assurance:

- □ Each report entered is reviewed by a member of the Close Call Reporting System project team within 24 hours.

- □ Any staff names or ID numbers, patient names, or medical record numbers are removed from records.

- □ If a report is found to have data that actually indicate that the occurrence did reach the patient, a designated contact for that hospital will be contacted immediately.

Compliance:

- □ System complies with all Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements.

- □ System complies with all HIPAA mandates as followed by the University of Texas system.

- □ Some customizations can be made for each participating location to assure localized compliance.

Security:

- □ System is set up on dual servers (separate database and Web servers) with the database placed behind a secure firewall.

- □ System is monitored 24/7 for unauthorized access or “hacking” attempts.

- □ System is protected by the most up to date virus protection available.

- □ System has internal monitors set to page support personnel should there be a system failure.

- □ Regular backups of the data are performed

References

- 1.

- Edmondson A. Learning from failure in health care: Frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii3–ii9. [PMC free article: PMC1765808] [PubMed: 15576689]

- 2.

- Furukawa H, Bunko H, Tsuchiya F, et al. Voluntary medication error reporting program in a Japanese national university hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1716–1722. [PubMed: 14565814]

- 3.

- Mutter M. One hospital’s journey toward reducing medication errors. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:279–288. [PubMed: 14564746]

- 4.

- Stump LS. Re-engineering the medication error-reporting process: Removing the blame and improving the system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57( Suppl 4):S10–S17. [PubMed: 11148939]

- 5.

- The University of Texas. Close Call Reporting System. The University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice. [Accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at: www

.utccrs.org/ccrs/home.jsp. - 6.

- Poniatowski L, Stanley S, Youngberg B. Using information to empower nurse managers to become champions for patient safety. Nurs Adm Q. 2005;29:72–77. [PubMed: 15779708]

- 7.

- Corrigan JM, Kohn LT, editors. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed: 25077248]

- 8.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed: 25057539]

- 9.

- Cohen MR. Medication errors. Washington, DC: APhA Publications; 2006.

- 10.

- Institute of Medicine. Keeping patients safe: Transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed: 25009891]

- 11.

- Aspden P, Corrigan JM, Wolcott J, et al., editors. Patient safety: Achieving a new standard of care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed: 25009854]

- 12.

- Wakefield DS, Wakefield BJ, Uden-Holman T, et al. Perceived barriers in reporting medication administration errors. Best Pract Benchmarking Healthc. 1996;1:191–197. [PubMed: 9192569]

- 13.

- Martin SK, Etchegaray JM, Simmons D, et al. Advances in patient safety: From research to implementation. Vol. 2, Concepts and methodology. AHRQ Pub. 05-0021-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [Accessed April 3, 2008]. Development and implementation of the University of Texas close call reporting system. Available at: www

.ahrq.gov/downloads /pub/advances/vol2/Martin.pdf. [PubMed: 21249824] - 14.

- Bagian JP, Gosbee JW. Developing a culture of patient safety at the VA. Ambul Outreach. 2000:25–29. [PubMed: 11067444]

- 15.

- Barach P, Small SD. How the NHS can improve safety and learning. By learning free lessons from near misses. Br Med J. 2000;320:1683–1684. [PMC free article: PMC1127461] [PubMed: 10864524]

- 16.

- Marx D. Patient safety and the “just culture”: A primer for health care executives. New York: Columbia University; 2001. p. 28.

- 17.

- Simpson RL. Winning the “blame game. Nurs Manage. 2002;33:14–16. [PubMed: 11984316]

- 18.

- Hritz RW, Everly JL, Care SA. Medication error identification is a key to prevention: A performance improvement approach. J Healthc Qual. 2002;24:10–17. [PubMed: 11942151]

- 19.

- Cohen MM, Kimmel NL, Benage MK, et al. Implementing a hospitalwide patient safety program for cultural change. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30:424–431. [PubMed: 15357132]

- 20.

- Smith DS, Haig K. Reduction of adverse drug events and medication errors in a community hospital setting. Nurs Clin North Am. 2005;40:25–32. [PubMed: 15733944]

- 21.

- Coyle GA. Designing and implementing a close call reporting system. Nurs Adm Q. 2005;29:57–62. [PubMed: 15779706]

- 22.

- Battles JB, Dixon NM, Borotkanics RJ, et al. Sensemaking of patient safety risks and hazards. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 2):1555–1575. [PMC free article: PMC1955349] [PubMed: 16898979]

- Review Development and Implementation of The University of Texas Close Call Reporting System.[Advances in Patient Safety: Fr...]Review Development and Implementation of The University of Texas Close Call Reporting System.Martin SK, Etchegaray JM, Simmons D, Belt WT, Clark K. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology). 2005 Feb

- The good catch pilot program: increasing potential error reporting.[J Nurs Adm. 2007]The good catch pilot program: increasing potential error reporting.Mick JM, Wood GL, Massey RL. J Nurs Adm. 2007 Nov; 37(11):499-503.

- Evaluating a community-based program to improve healthcare quality: research design for the Aligning Forces for Quality initiative.[Am J Manag Care. 2012]Evaluating a community-based program to improve healthcare quality: research design for the Aligning Forces for Quality initiative.Scanlon DP, Alexander JA, Beich J, Christianson JB, Hasnain-Wynia R, McHugh MC, Mittler JN, Shi Y, Bodenschatz LJ. Am J Manag Care. 2012 Sep; 18(6 Suppl):s165-76.

- Development and implementation of the TrAC (Tracking After-hours Calls) database: a tool to collect longitudinal data on after-hours telephone calls in long-term care.[J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007]Development and implementation of the TrAC (Tracking After-hours Calls) database: a tool to collect longitudinal data on after-hours telephone calls in long-term care.Hastings SN, Whitson HE, White HK, Sloane R, MacDonald H, Lekan-Rutledge DA, McConnell ES. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007 Mar; 8(3):178-82.

- Review The AAFP Patient Safety Reporting System: Development and Legal Issues Pertinent to Medical Error Tracking and Analysis.[Advances in Patient Safety: Fr...]Review The AAFP Patient Safety Reporting System: Development and Legal Issues Pertinent to Medical Error Tracking and Analysis.Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Hickner JS, Graham D, Johnson M. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 3: Implementation Issues). 2005 Feb

- 26,000 Close Call Reports: Lessons from the University of Texas Close Call Repor...26,000 Close Call Reports: Lessons from the University of Texas Close Call Reporting System - Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 1: Assessment)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...